Содержание

- 2. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 How democratization occurs – a puzzle. Authoritarian ruling elite must

- 3. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Various theories suggest they do so deliberately… to credibly commit

- 4. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 All these assume the elite (or at least part of

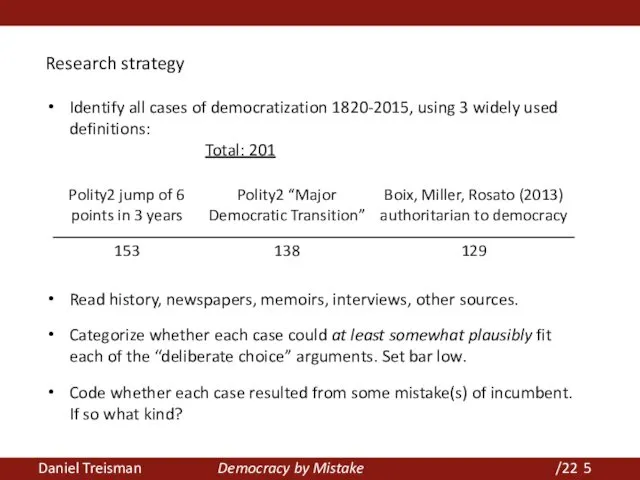

- 5. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Research strategy Identify all cases of democratization 1820-2015, using 3

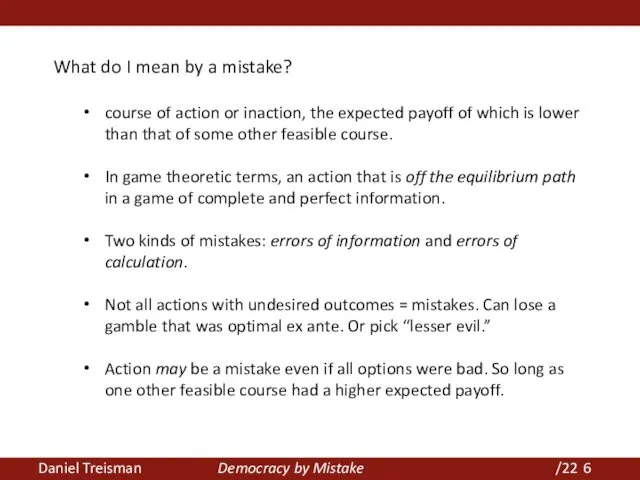

- 6. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 What do I mean by a mistake? course of action

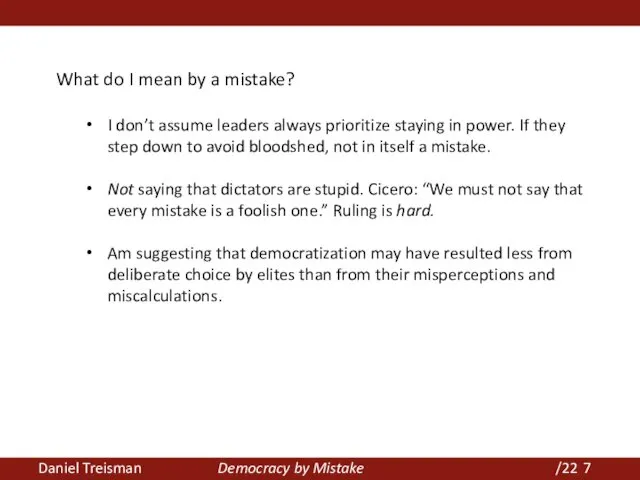

- 7. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 What do I mean by a mistake? I don’t assume

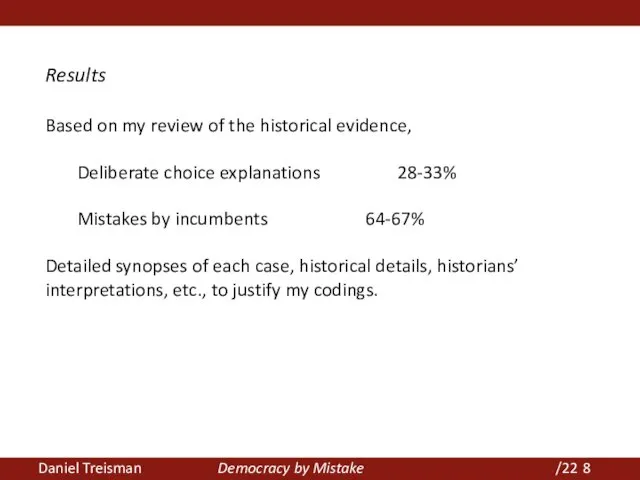

- 8. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Results Based on my review of the historical evidence, Deliberate

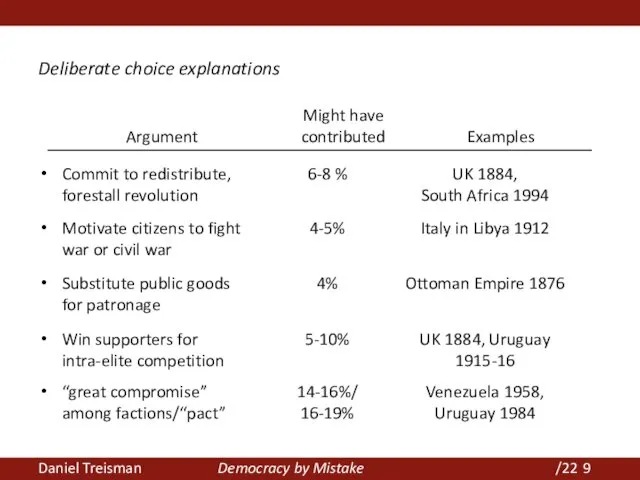

- 9. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Deliberate choice explanations

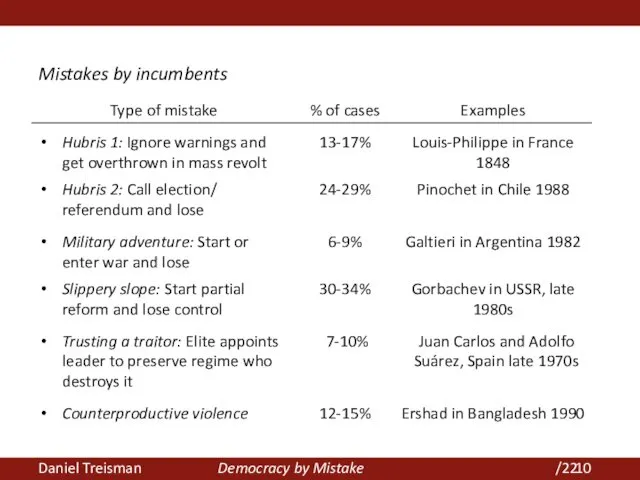

- 10. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Mistakes by incumbents

- 11. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 How do I decide how to classify cases? An example:

- 12. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Did a rich elite democratize to commit to redistribution to

- 13. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Did the military democratize to motivate citizens to fight or

- 14. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Was it a case of one elite faction broadening access

- 15. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Democratization by mistake? Yes—military adventure. Junta did not mean to

- 16. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Robustness: Does it make a difference to the results which

- 17. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Of course, not saying all mistakes of dictators lead to

- 18. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Why so many mistakes? Common cognitive biases and limitations -over-optimism

- 19. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Why so many mistakes? Pathologies of authoritarian leaders -hubris an

- 20. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Other types of institutional change where mistakes appear important Selection

- 21. Daniel Treisman Democracy by Mistake /22 Conclusions based on comprehensive review of historical cases, democratization was

- 23. Скачать презентацию

Формирование политической карты мира

Формирование политической карты мира Отношения между США и Японией

Отношения между США и Японией Політичний режим Китаю

Політичний режим Китаю Идеал личности в Китае

Идеал личности в Китае Солтүстік Атлантикалық Келісім Ұйымы

Солтүстік Атлантикалық Келісім Ұйымы Саясат субъектілері

Саясат субъектілері Политка и спорт в РФ

Политка и спорт в РФ Фашизм и неофашизм

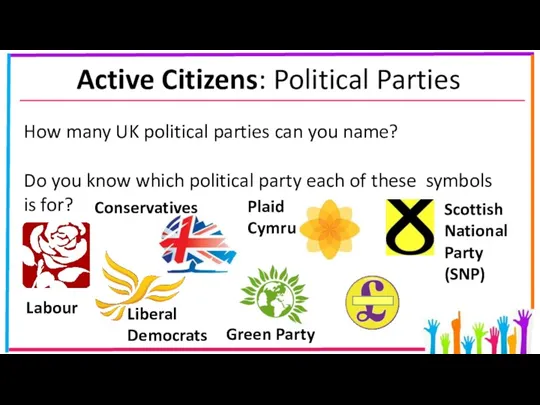

Фашизм и неофашизм Active Citizens: Political Parties

Active Citizens: Political Parties Политическая система общества

Политическая система общества Политическое лидерство

Политическое лидерство Русский Бисмарк, электронная выставка к 155-летию П.А. Столыпина

Русский Бисмарк, электронная выставка к 155-летию П.А. Столыпина Соціальна відповідальность в процесі реалізації права володіння, користування, розпорядження національним капіталом

Соціальна відповідальность в процесі реалізації права володіння, користування, розпорядження національним капіталом Реалізація державної політики у сфері державної реєстрації фізичних осіб, департаментом реєстраційних послуг Запорізької ради

Реалізація державної політики у сфері державної реєстрації фізичних осіб, департаментом реєстраційних послуг Запорізької ради Основные этапы становления и развития политической науки

Основные этапы становления и развития политической науки Правовое государство и гражданское общество

Правовое государство и гражданское общество Историческая эволюция многосторонней дипломатии

Историческая эволюция многосторонней дипломатии Россия - Украина. Беседа о важном

Россия - Украина. Беседа о важном Политическая система и политический режим

Политическая система и политический режим Пути развития народов Азии, Африки и Латинской Америки

Пути развития народов Азии, Африки и Латинской Америки Социализм. Основные принципы учения

Социализм. Основные принципы учения Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев

Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев Kristi Klaamann. Eesti avalik haldus

Kristi Klaamann. Eesti avalik haldus Наиболее сложные вопросы по обществознанию в разделе Политика

Наиболее сложные вопросы по обществознанию в разделе Политика Модель соціальної політики Сполучених Штатів Америки

Модель соціальної політики Сполучених Штатів Америки Социальная политика государства. (Тема 15)

Социальная политика государства. (Тема 15) Политическая система общества. Лекция 5

Политическая система общества. Лекция 5 Лидеры и элиты в политической жизни

Лидеры и элиты в политической жизни