Содержание

- 4. BASIC NOTIONS OF SEMANTICS

- 5. PLAN FOR TODAY Word meaning: concepts and reference, sense and denotation Linguistic signs and the semiotic

- 6. Compare a linguistic symbol like ’cat’ to the road sign below. What are the similarities and

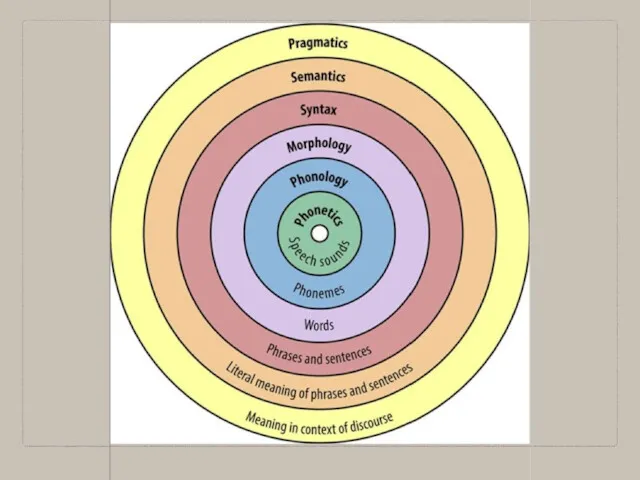

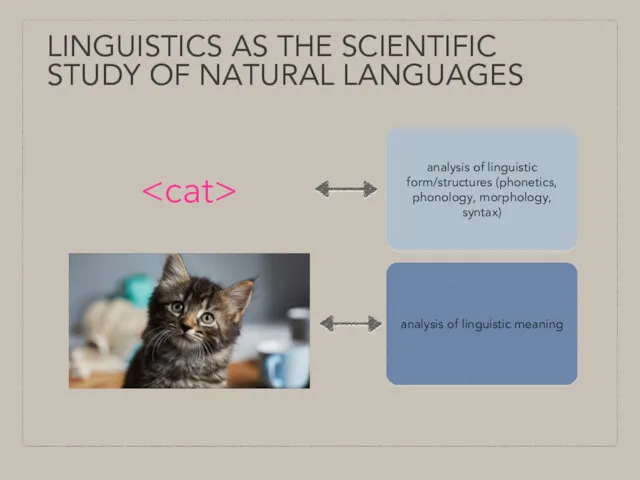

- 7. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES form

- 8. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES concept, meaning

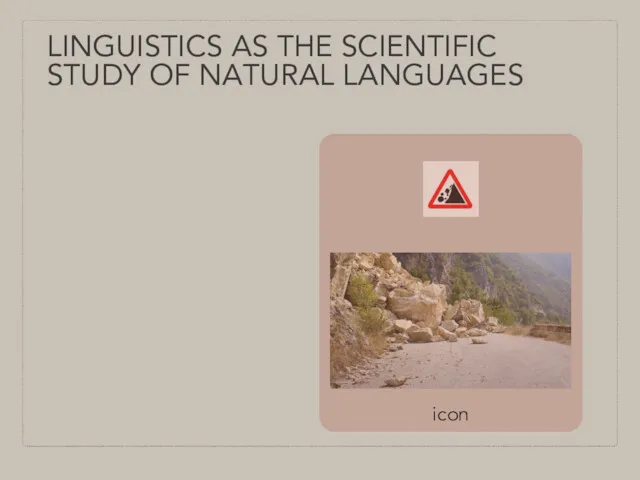

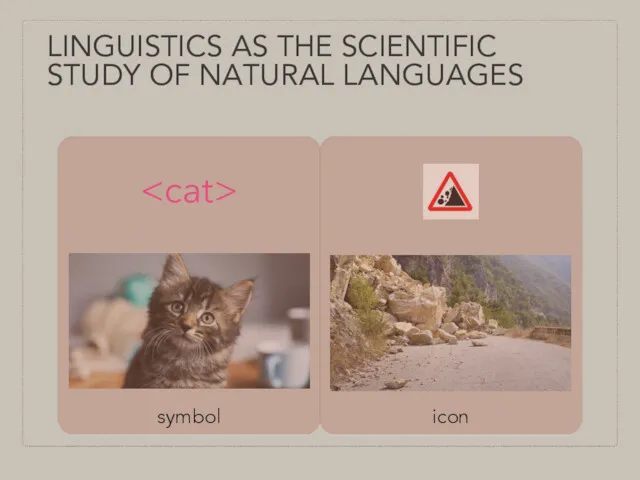

- 9. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES icon

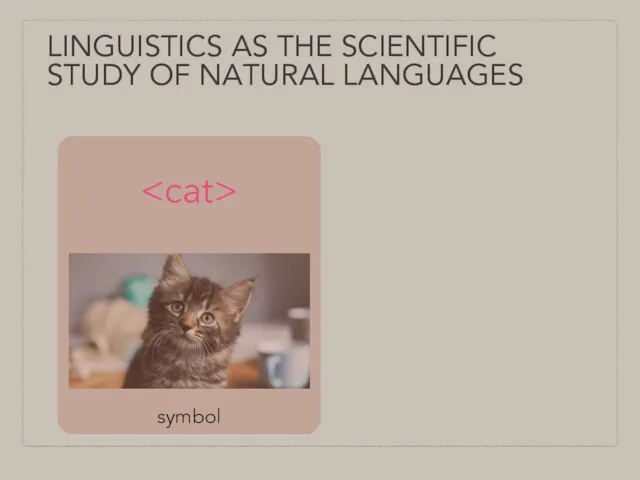

- 10. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES symbol

- 11. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES symbol icon

- 12. – In which respects is this statement true, and in which respects is it not true?

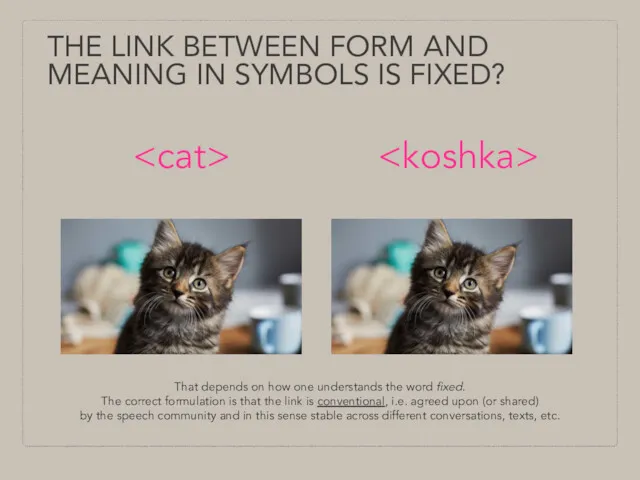

- 13. THE LINK BETWEEN FORM AND MEANING IN SYMBOLS IS FIXED? That depends on how one understands

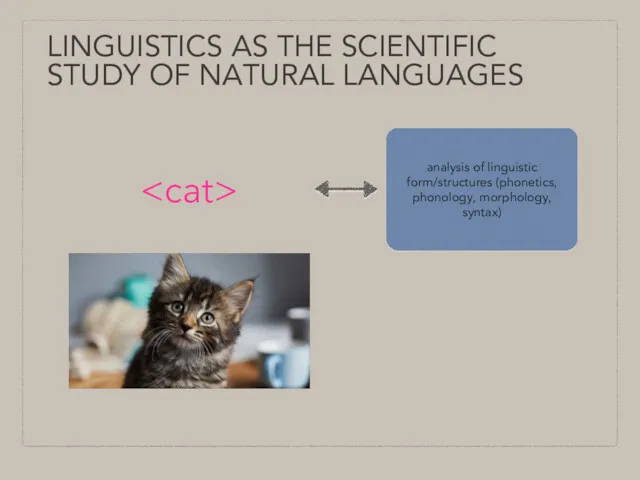

- 14. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES analysis of linguistic form/structures (phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax)

- 15. LINGUISTICS AS THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF NATURAL LANGUAGES analysis of linguistic form/structures (phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax)

- 16. SEMANTICS denotation reference

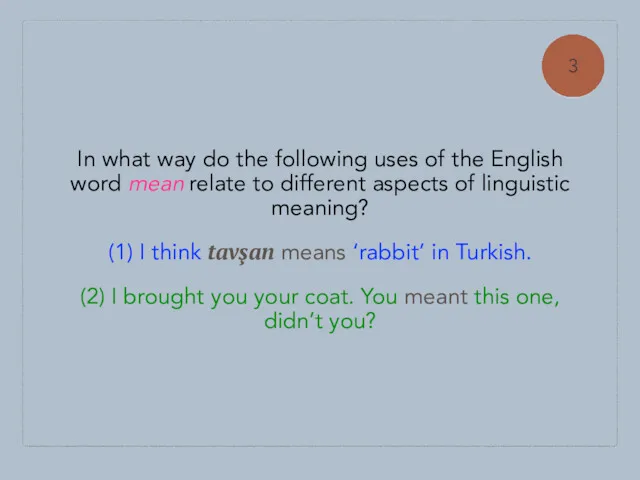

- 17. In what way do the following uses of the English word mean relate to different aspects

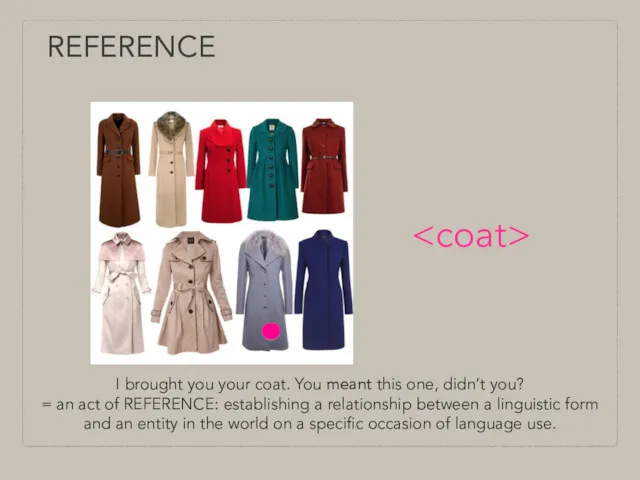

- 18. REFERENCE Please bring me my coat.

- 19. REFERENCE I brought you your coat. You meant this one, didn’t you?

- 20. REFERENCE I brought you your coat. You meant this one, didn’t you? = an act of

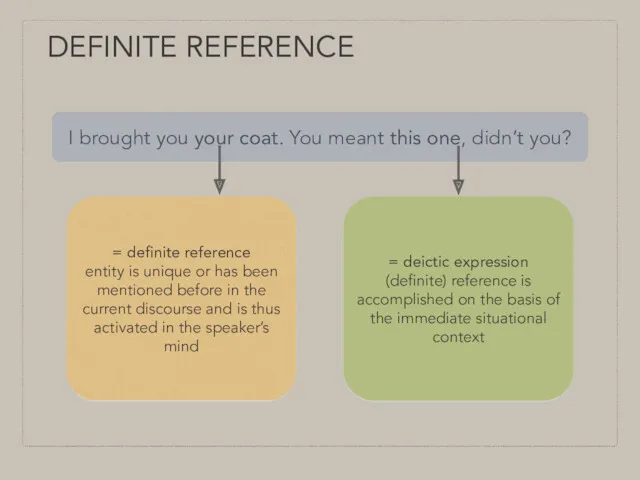

- 21. DEFINITE REFERENCE I brought you your coat. You meant this one, didn’t you? = definite reference

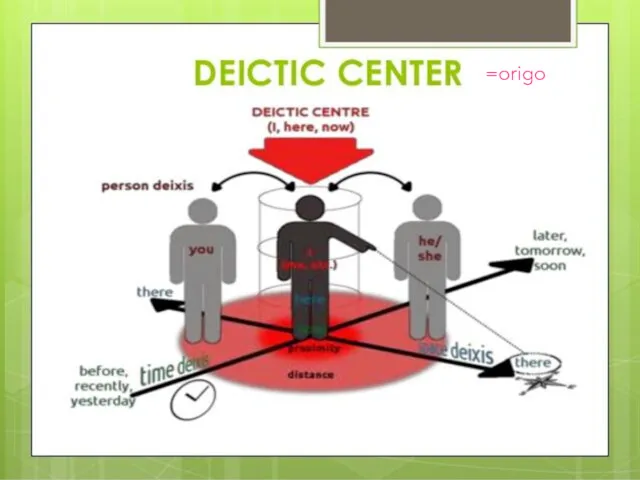

- 22. =origo

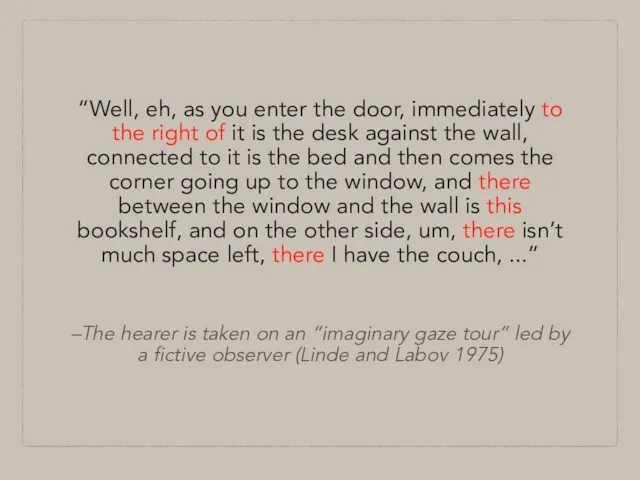

- 23. –The hearer is taken on an “imaginary gaze tour” led by a fictive observer (Linde and

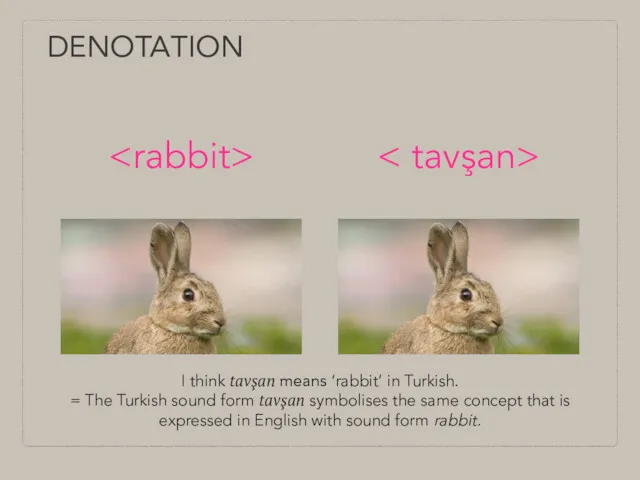

- 24. DENOTATION I think tavşan means ‘rabbit’ in Turkish. = The Turkish sound form tavşan symbolises the

- 25. – Cruse 2004: 125 “The most direct connections of linguistic forms (phonological or syntactic) are with

- 26. GAVAGAI PROBLEM Imagine a linguist who comes across a culture whose language is entirely foreign to

- 27. In their early stages of language acquisition, young children often initially apply a word like ’car’

- 28. UNDEREXTENSION initial failure to accept that words do not usually have a single referent but a

- 29. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE

- 30. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE

- 31. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE mental category, concept

- 32. Concepts can be described in terms of properties which are important for classifying an object as

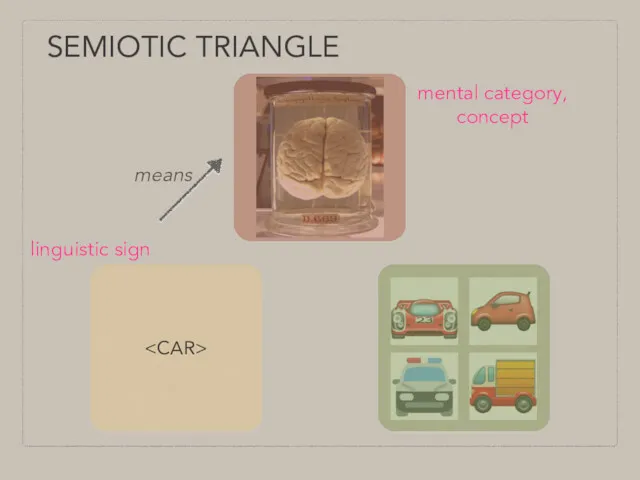

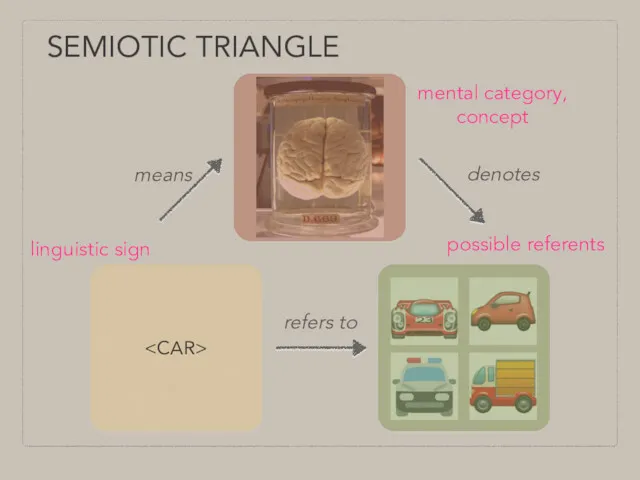

- 33. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE mental category, concept linguistic sign means

- 34. Meaning is the relation between a linguistic expression (i.e. an arbitrary form, e.g. a word) and

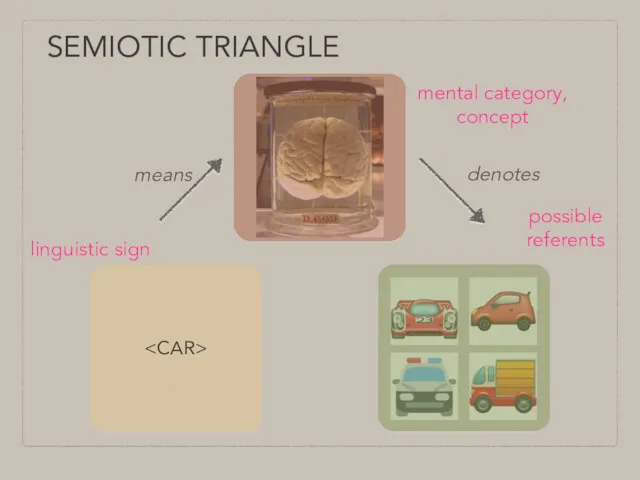

- 35. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE mental category, concept linguistic sign means denotes possible referents

- 36. Denotation is the relation between the entire class of objects to which an expression correctly refers

- 37. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE mental category, concept linguistic sign means denotes possible referents refers to

- 38. Reference is the act of establishing a relationship between a linguistic expression and an object in

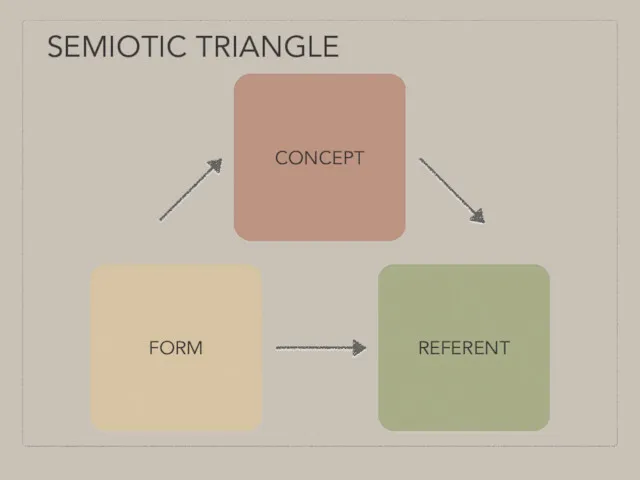

- 39. SEMIOTIC TRIANGLE FORM REFERENT CONCEPT

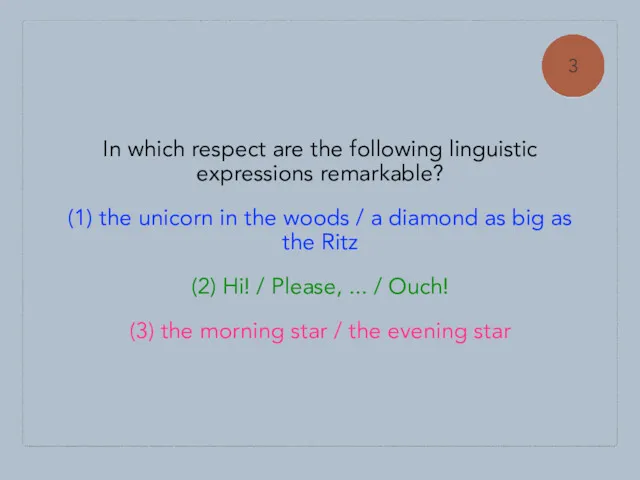

- 40. In which respect are the following linguistic expressions remarkable? (1) the unicorn in the woods /

- 41. CONCEPTS & REFERENTS Distinguishing between sense and reference solves a number of puzzles: Some words/phrases do

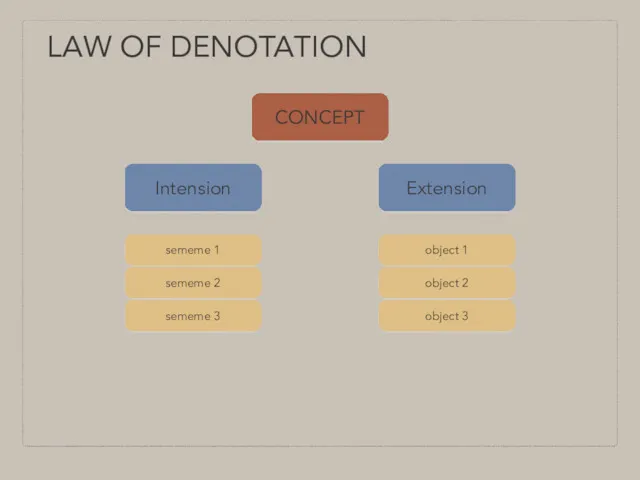

- 42. LAW OF DENOTATION Intension Extension CONCEPT

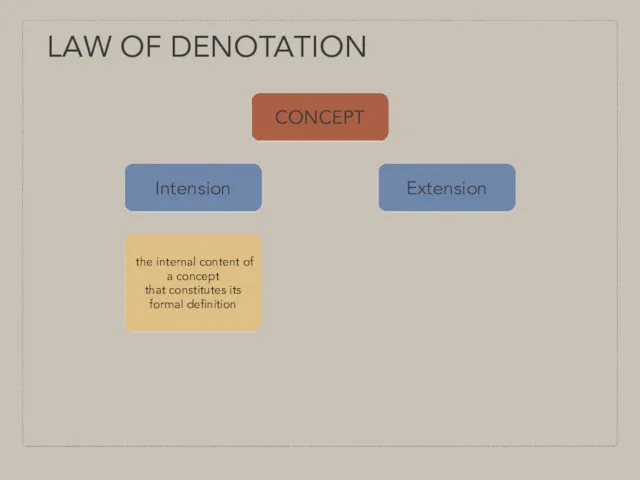

- 43. LAW OF DENOTATION Intension Extension the internal content of a concept that constitutes its formal definition

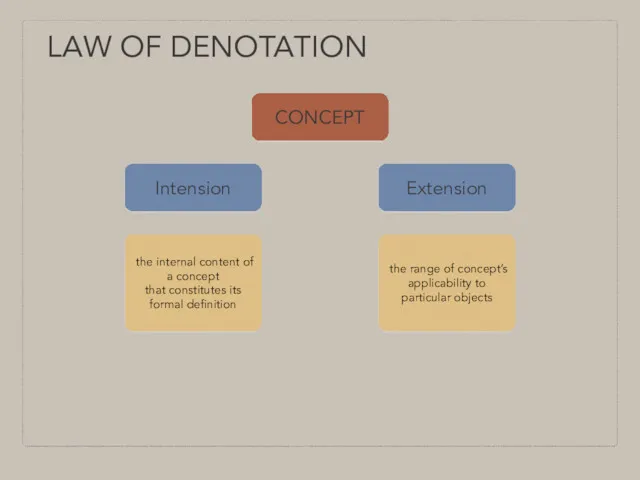

- 44. LAW OF DENOTATION Intension Extension the internal content of a concept that constitutes its formal definition

- 45. LAW OF DENOTATION Intension Extension sememe 1 CONCEPT sememe 2 sememe 3 object 1 object 2

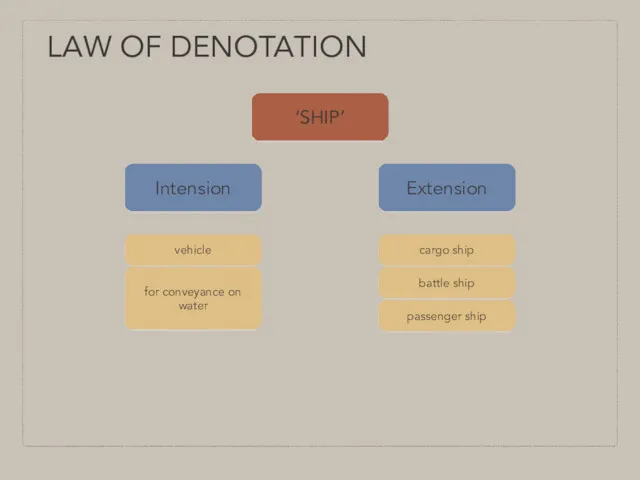

- 46. LAW OF DENOTATION Intension Extension vehicle ‘SHIP’ for conveyance on water cargo ship battle ship passenger

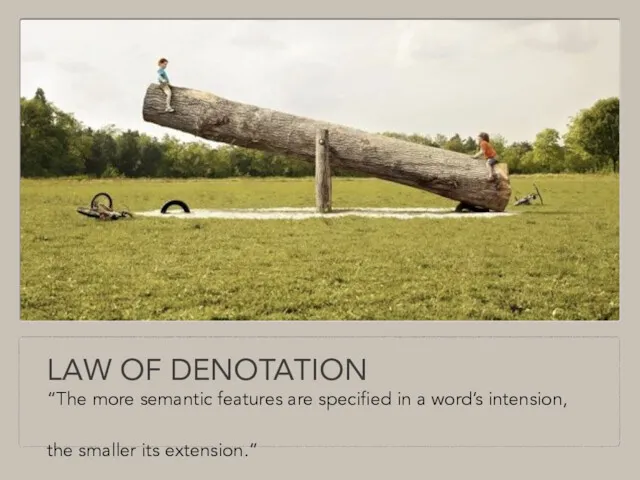

- 47. LAW OF DENOTATION “The more semantic features are specified in a word’s intension, the smaller its

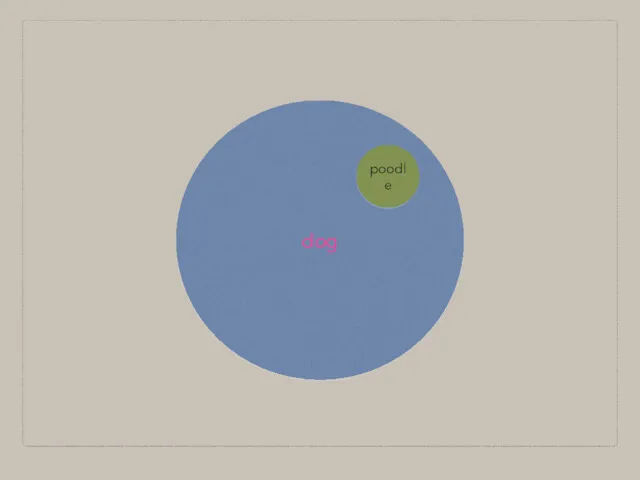

- 48. dog poodle

- 49. dog poodle domestic mammal closely related to the gray wolf

- 50. dog poodle domestic mammal closely related to the gray wolf any of a breed of intelligent

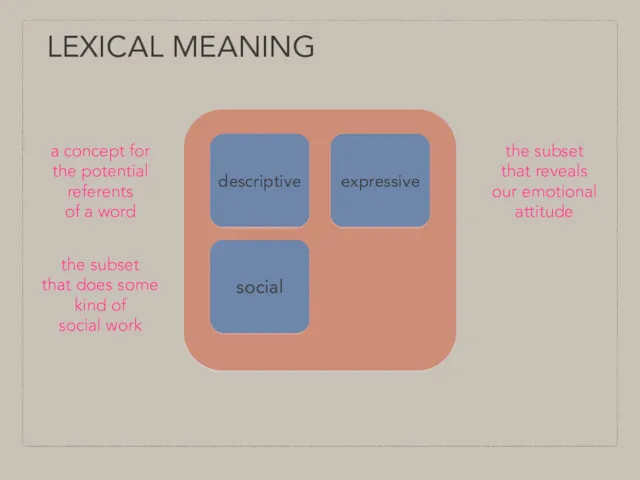

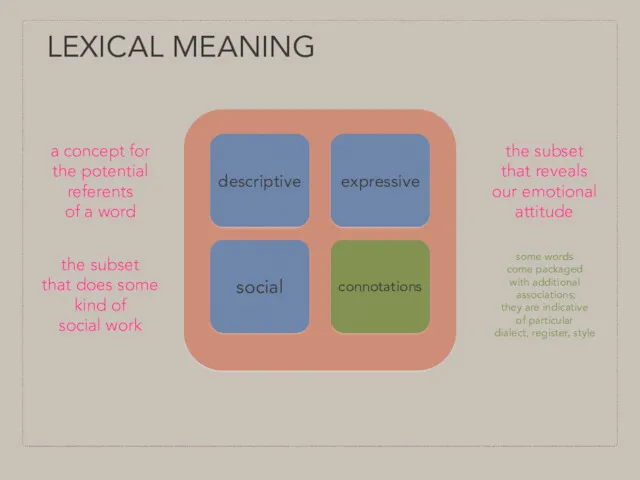

- 51. LEXICAL MEANING {set of semantic features}

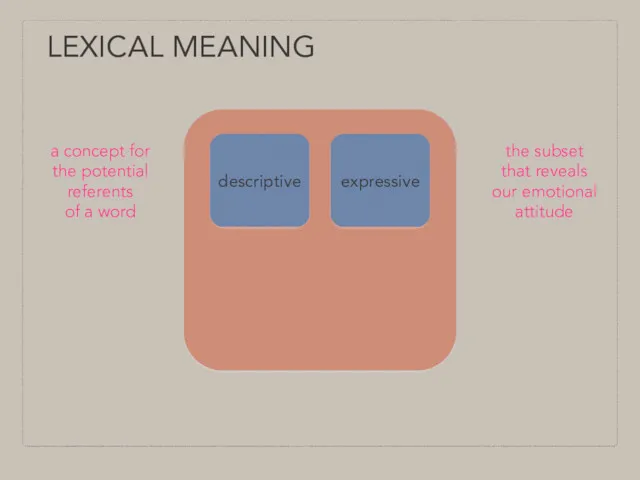

- 52. LEXICAL MEANING descriptive a concept for the potential referents of a word

- 53. LEXICAL MEANING expressive descriptive a concept for the potential referents of a word the subset that

- 54. LEXICAL MEANING A word has expressive meaning if it directly expresses (rather than describes) the speaker’s

- 55. LEXICAL MEANING Expressive meaning does not bear on descriptive meaning. The descriptive meaning of the sentence

- 56. LEXICAL MEANING social expressive descriptive a concept for the potential referents of a word the subset

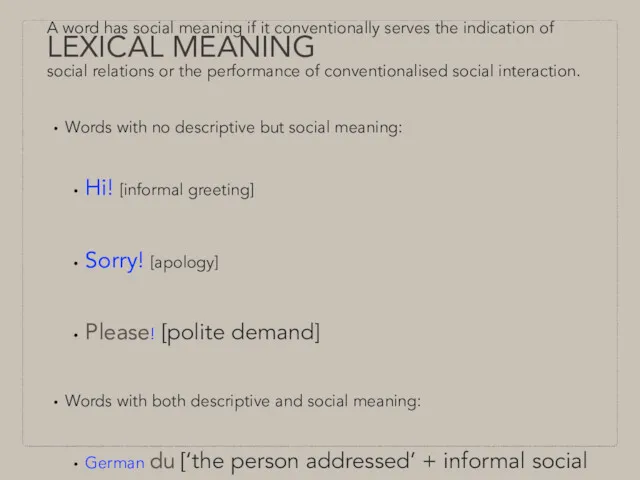

- 57. LEXICAL MEANING A word has social meaning if it conventionally serves the indication of social relations

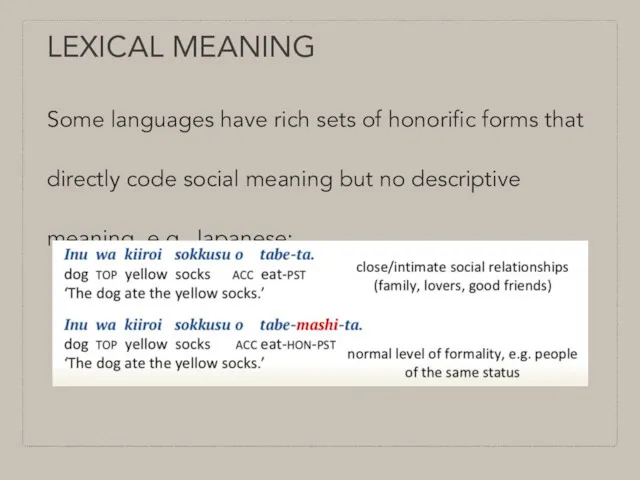

- 58. LEXICAL MEANING Some languages have rich sets of honorific forms that directly code social meaning but

- 59. LEXICAL MEANING connotations social expressive descriptive a concept for the potential referents of a word the

- 60. CONNOTATIONS Connotations are largely conventional (i.e. shared) associations of words based on their usage contexts or

- 61. THE NATURE OF CONCEPTS

- 62. PLAN FOR TODAY How can we characterise the conceptual content of a word? Different kinds of

- 63. The study of word meaning is known as __________ ___________. The word adult can _________ humans

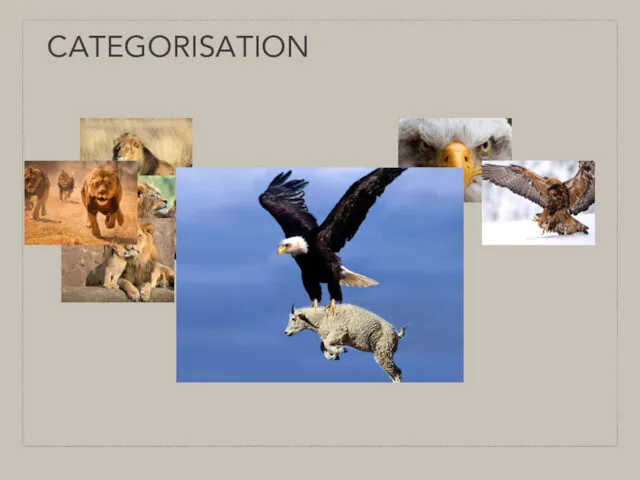

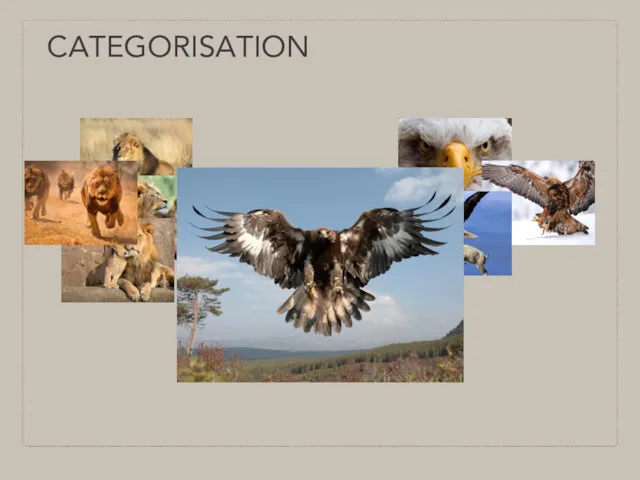

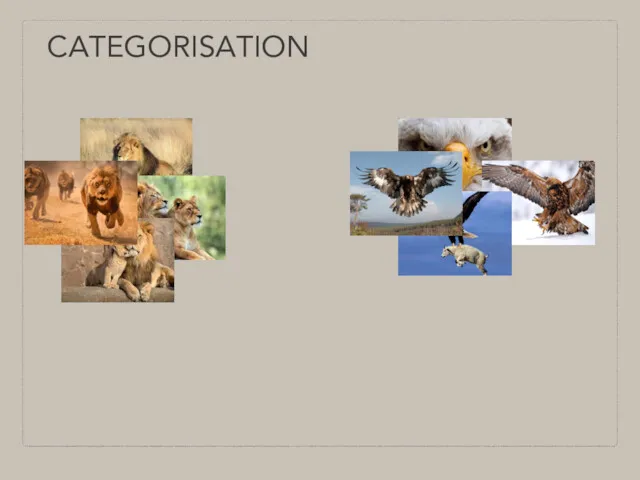

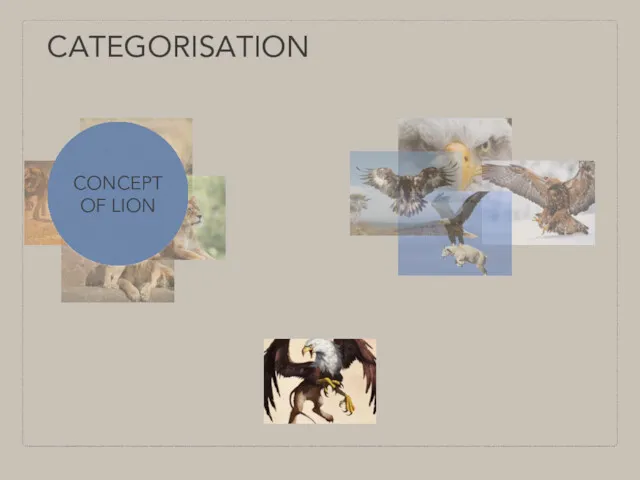

- 64. CATEGORISATION – Cruse 2004: 125 “If we were not able to assign aspects of our experience

- 65. CATEGORISATION

- 66. CATEGORISATION

- 67. CATEGORISATION

- 68. CATEGORISATION

- 69. CATEGORISATION

- 70. CATEGORISATION

- 71. CATEGORISATION

- 72. CATEGORISATION

- 73. CATEGORISATION

- 74. CATEGORISATION

- 75. CATEGORISATION

- 76. CATEGORISATION

- 77. CATEGORISATION CONCEPT OF LION

- 78. CATEGORISATION CONCEPT OF LION CONCEPT OF EAGLE

- 79. CATEGORISATION CONCEPT OF LION CONCEPT OF EAGLE CONCEPT OF GRIFFIN

- 80. THEORIES OF MEANING PROTOTYPE THEORY CLASSICAL ARISTOTELIAN VIEW

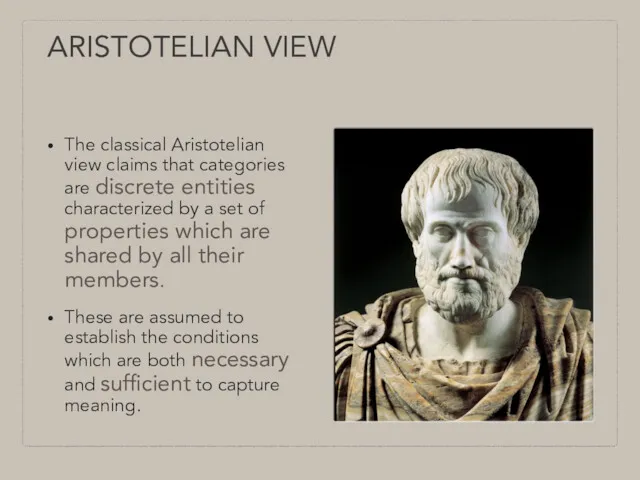

- 81. ARISTOTELIAN VIEW The classical Aristotelian view claims that categories are discrete entities characterized by a set

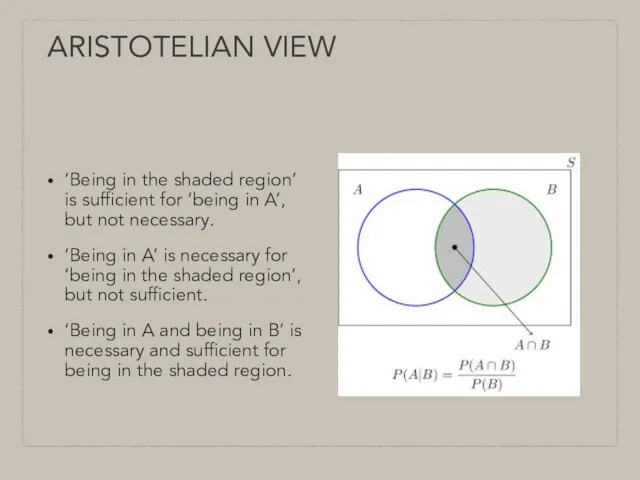

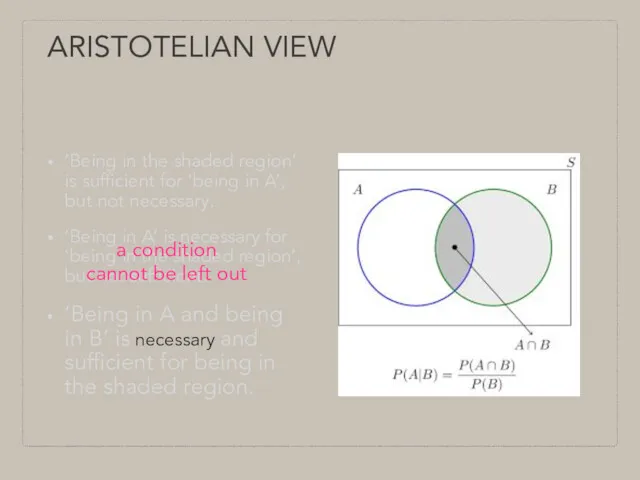

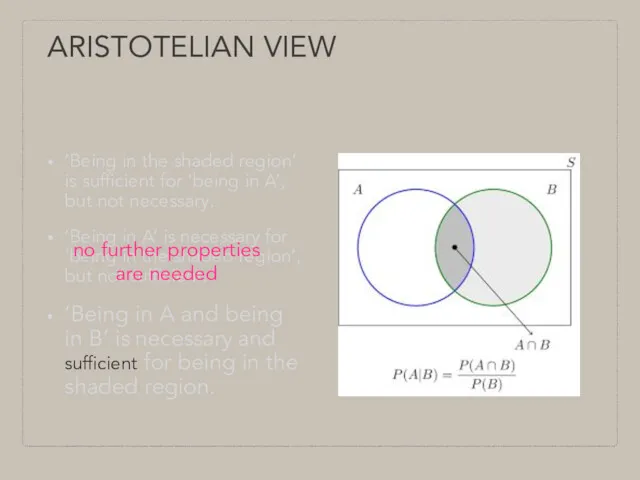

- 82. ARISTOTELIAN VIEW ‘Being in the shaded region’ is sufficient for ‘being in A’, but not necessary.

- 83. ARISTOTELIAN VIEW ‘Being in the shaded region’ is sufficient for ‘being in A’, but not necessary.

- 84. ARISTOTELIAN VIEW ‘Being in the shaded region’ is sufficient for ‘being in A’, but not necessary.

- 85. ARISTOTELIAN VIEW According to the classical view, categories should be clearly defined, mutually exclusive and collectively

- 86. According to third-century Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, Plato was applauded for his definition

- 87. According to third-century Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, Plato was applauded for his definition

- 88. According to third-century Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, Plato was applauded for his definition

- 89. PHILSOPHY & CLASSICAL SEMANTICS Assumption: just as the meaning of a sentence can be regularly built

- 90. PHILSOPHY & CLASSICAL SEMANTICS Necessary and sufficient conditions are taken to be part of the sense

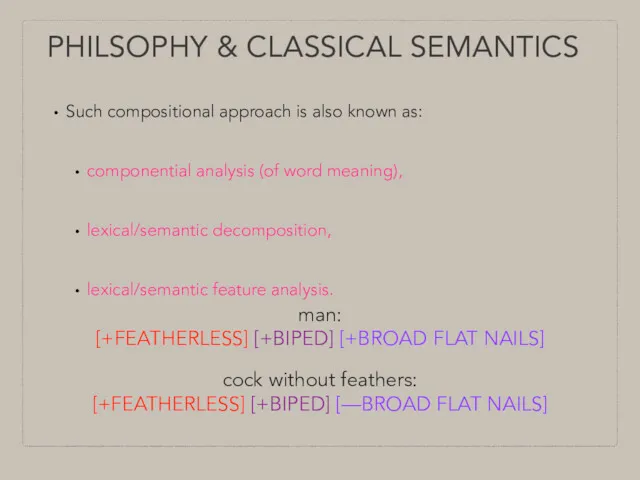

- 91. Such compositional approach is also known as: componential analysis (of word meaning), lexical/semantic decomposition, lexical/semantic feature

- 92. Such compositional approach is also known as: componential analysis (of word meaning), lexical/semantic decomposition, lexical/semantic feature

- 93. Such compositional approach is also known as: componential analysis (of word meaning), lexical/semantic decomposition, lexical/semantic feature

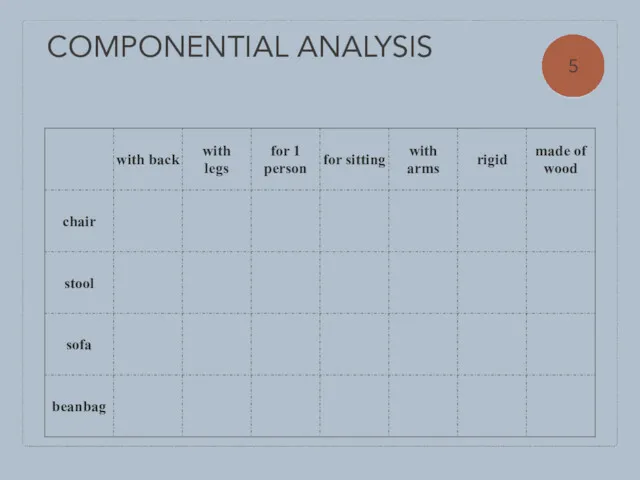

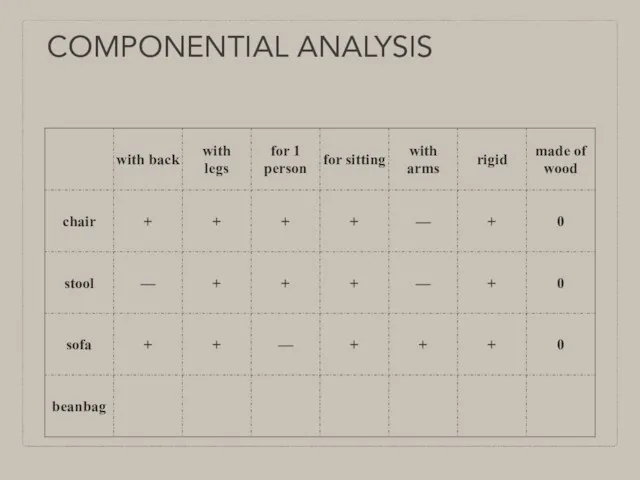

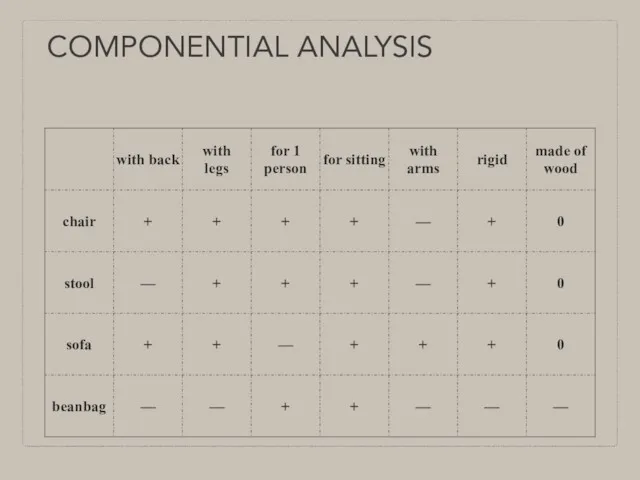

- 94. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS 5

- 95. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

- 96. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

- 97. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

- 98. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

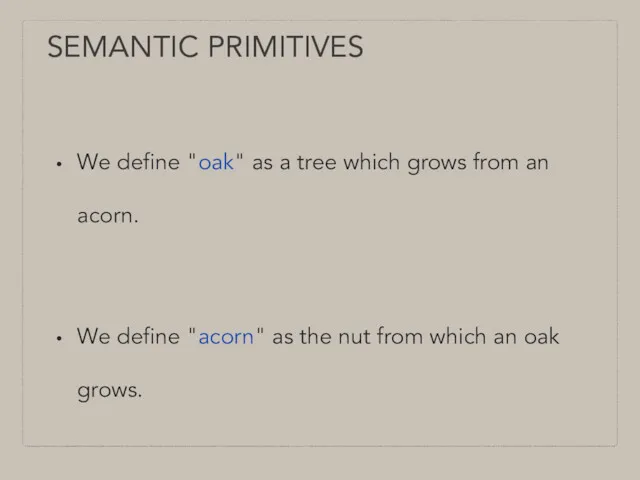

- 99. Componential approaches reduce complex meanings to a finite set of semantic “building blocks” called primitives. A

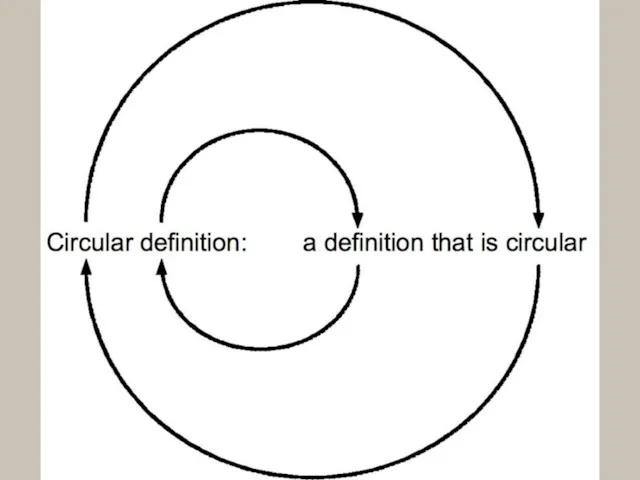

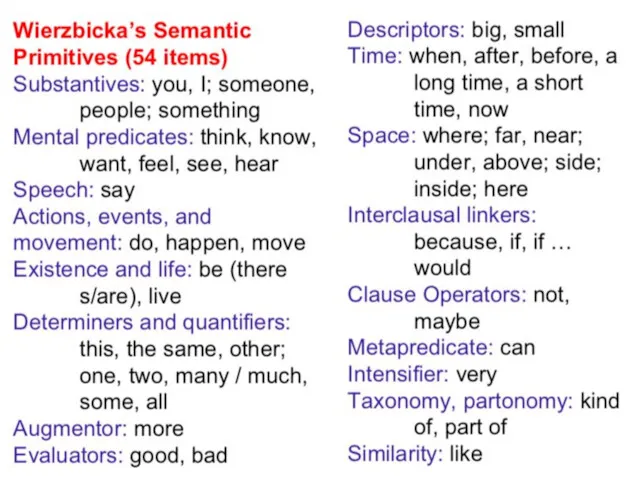

- 100. Anna Wierzbicka’s Natural Semantic Metalanguage. Can the study of meaning be rigorous and scientific? Yes, and

- 102. We define "oak" as a tree which grows from an acorn. We define "acorn" as the

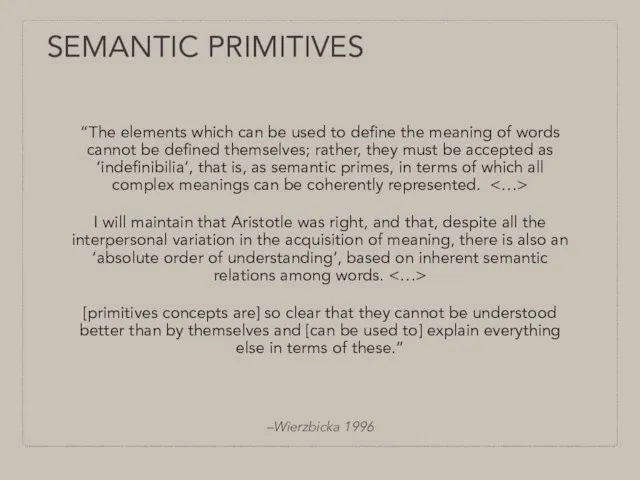

- 103. –Wierzbicka 1996 “The elements which can be used to define the meaning of words cannot be

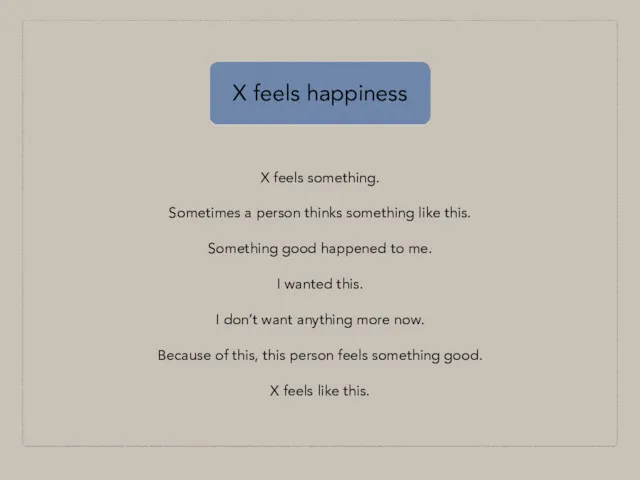

- 105. 6 Using the set of semantic primitives, try to describe the meaning of happiness.

- 106. X feels something. Sometimes a person thinks something like this. Something good happened to me. I

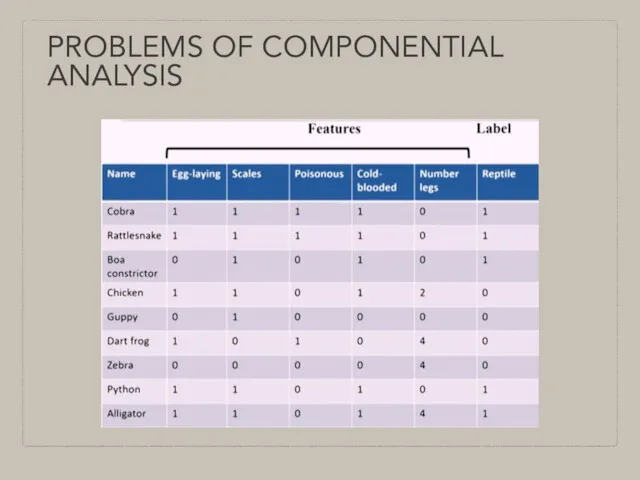

- 107. PROBLEMS OF COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

- 108. PROBLEMS OF COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS “In real life, [. . . ], there are many things that

- 109. PROBLEMS OF COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS Besides, many words cannot be sufficiently analysed by simple features. For example,

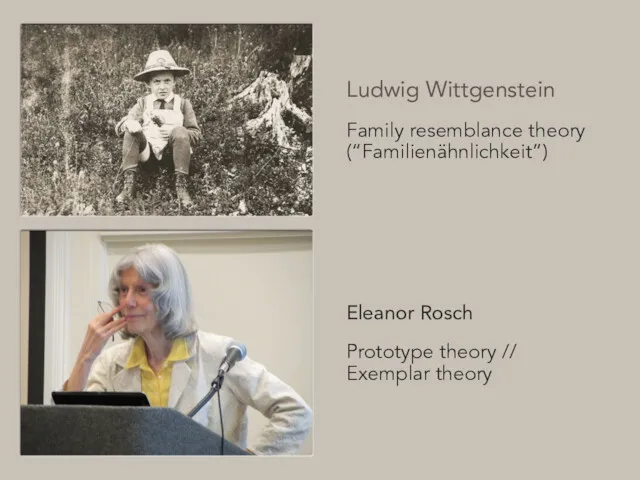

- 110. Ludwig Wittgenstein Family resemblance theory (“Familienähnlichkeit”) Eleanor Rosch Prototype theory // Exemplar theory

- 111. FAMILY RESEMBLANCE “Look for example at board games, with their multifarious relationships. Now pass to card

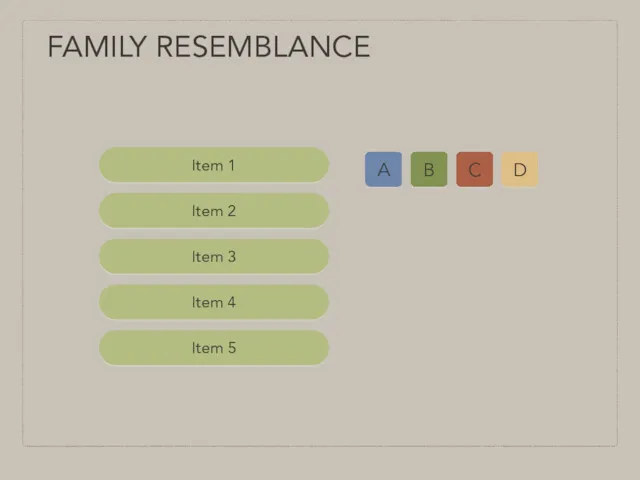

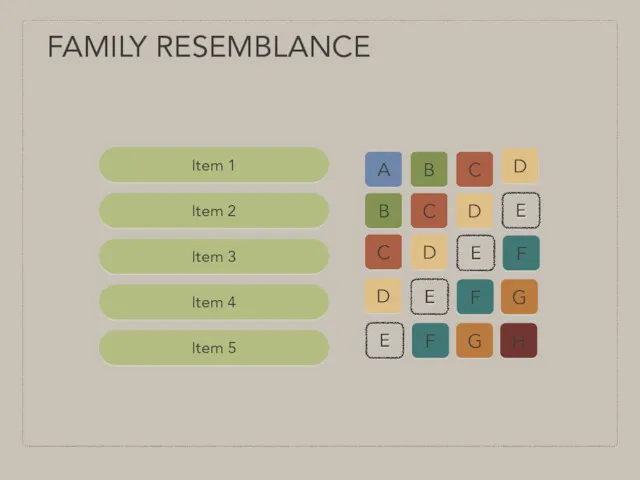

- 112. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D Item 2 Item 3 Item 4 Item 5

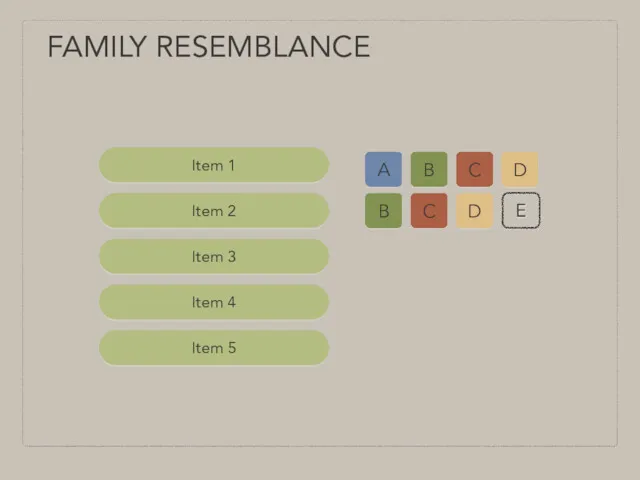

- 113. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D B C D Item 2 Item 3 Item

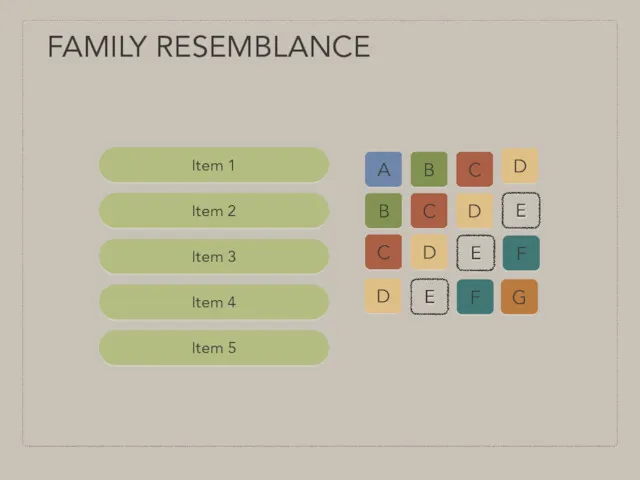

- 114. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D B C D C D F Item 2

- 115. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D B C D C D F D F

- 116. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D B C D C D F D F

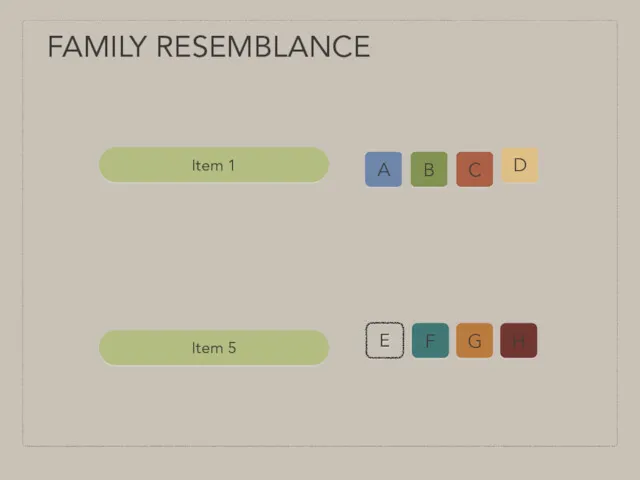

- 117. Item 1 FAMILY RESEMBLANCE A B C D F G H Item 5

- 118. https://forms.gle/it5kt2wbs6fAMXGw5 PROTOTYPE (EXEMPLAR) THEORY 7

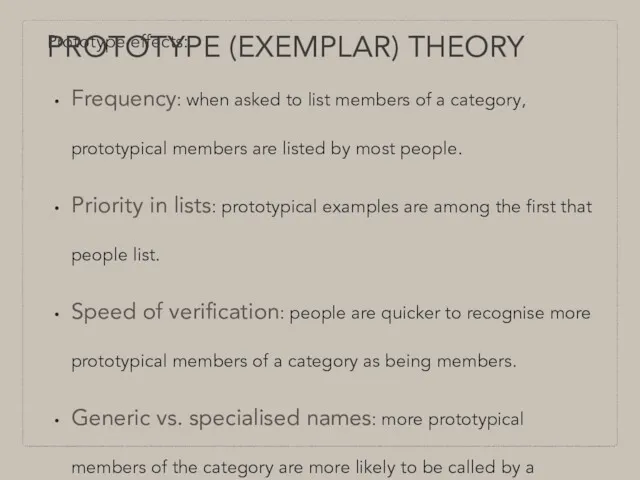

- 119. Prototype effects: Frequency: when asked to list members of a category, prototypical members are listed by

- 120. There are categories in which some members are better exemplars of the category than others. There

- 121. The two theories are similar in that they emphasize the importance of similarity in categorization: only

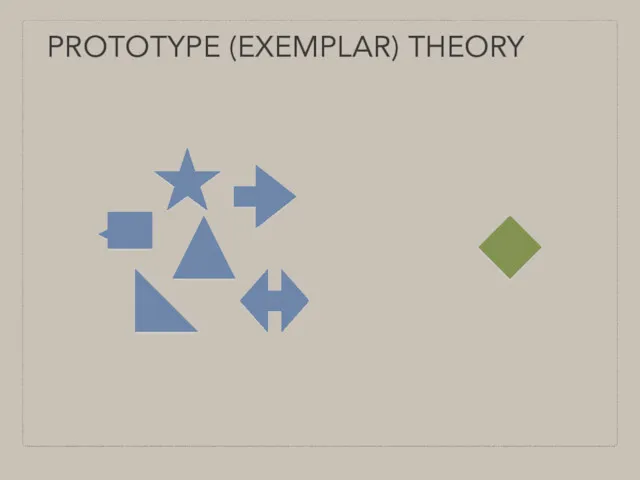

- 122. PROTOTYPE (EXEMPLAR) THEORY

- 123. The two theories are similar in that they emphasize the importance of similarity in categorization: only

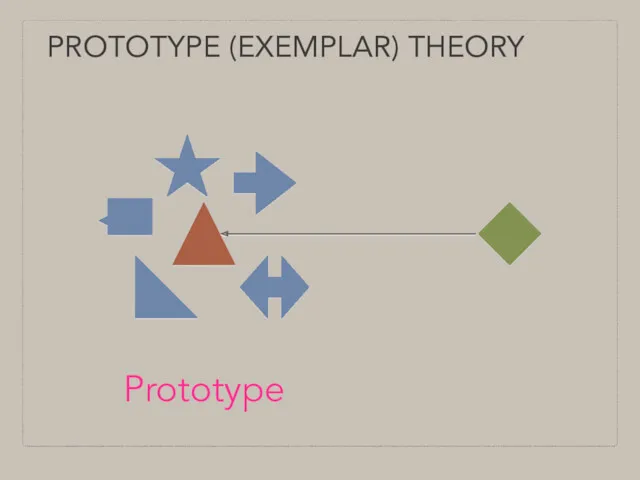

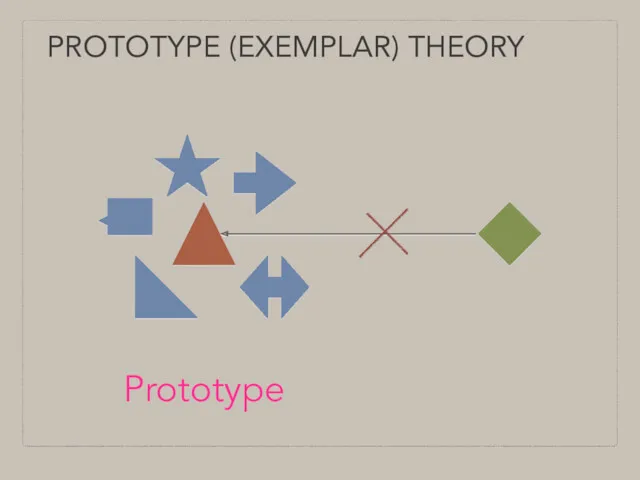

- 124. PROTOTYPE (EXEMPLAR) THEORY Prototype

- 125. PROTOTYPE (EXEMPLAR) THEORY Prototype

- 126. The two theories are similar in that they emphasize the importance of similarity in categorization: only

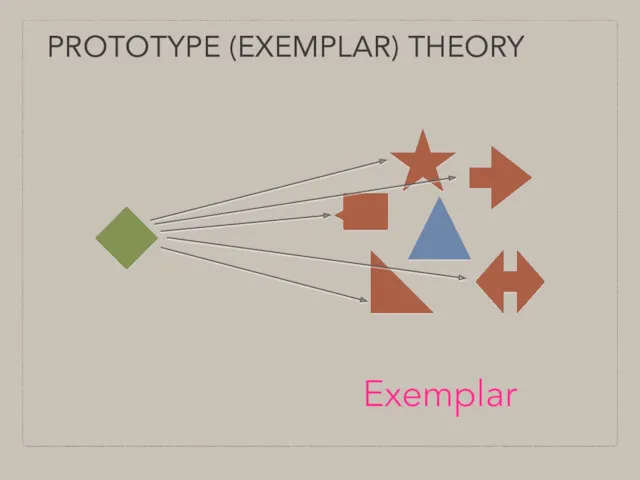

- 127. PROTOTYPE (EXEMPLAR) THEORY Exemplar

- 129. Скачать презентацию

Власне українська та іншомовна лексика у професійному мовленні. Виробничо-професійні терміни

Власне українська та іншомовна лексика у професійному мовленні. Виробничо-професійні терміни Грамматика

Грамматика Латинский язык 10

Латинский язык 10 Английский в картинках

Английский в картинках Финский язык в современном мире

Финский язык в современном мире Сәуірдің алтысы Сынып жұмысы “Абай”

Сәуірдің алтысы Сынып жұмысы “Абай” Использование интерактивной доки в учебном процессе

Использование интерактивной доки в учебном процессе Аффиксы имени действия (Исем фигыль)

Аффиксы имени действия (Исем фигыль) Ойын сабак

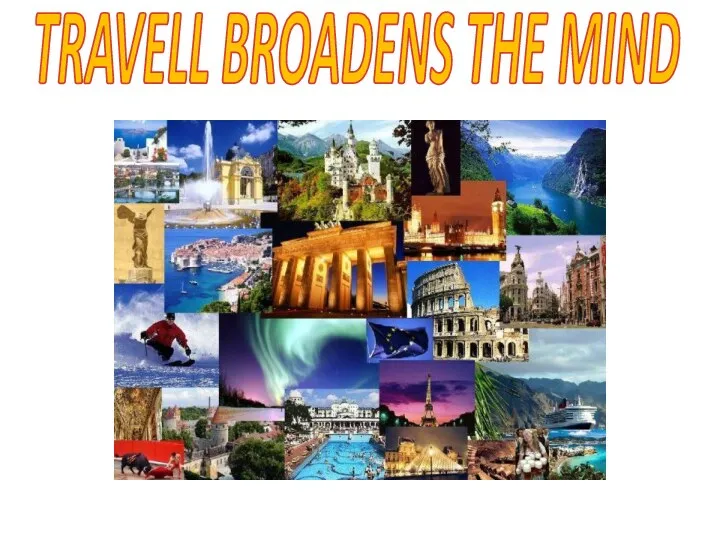

Ойын сабак Презентация к уроку I am a tourist

Презентация к уроку I am a tourist [Открытые уроки] Последовательная и параллельная электрическая цепь

[Открытые уроки] Последовательная и параллельная электрическая цепь Відмінювання числівників

Відмінювання числівників Такие разные адреса

Такие разные адреса Лингвопсихологические основы обучения иностранному языку

Лингвопсихологические основы обучения иностранному языку Faisons la fête. 5 класс. Интегрированный урок (французский язык+технология)

Faisons la fête. 5 класс. Интегрированный урок (французский язык+технология) Flowers

Flowers Сыйфат. 6 кл

Сыйфат. 6 кл Презентация к уроку английского языка по теме Множественное чмсло имен существительных

Презентация к уроку английского языка по теме Множественное чмсло имен существительных Службові частини мови

Службові частини мови Дієприкметник – особлива змінювана форма дієслова

Дієприкметник – особлива змінювана форма дієслова Методический семинар ( на конкурс Учитель года-2015)

Методический семинар ( на конкурс Учитель года-2015) Сөздің лексика-семантикалық табиғаты

Сөздің лексика-семантикалық табиғаты Презентация курса с ИКТ-поддержкой

Презентация курса с ИКТ-поддержкой Найголовніші правила пунктуації

Найголовніші правила пунктуації Автоматизація звука [ж] у словах

Автоматизація звука [ж] у словах Исконная лексика и её основные типы

Исконная лексика и её основные типы Презентация по английскому языку 45 урок Биболетова

Презентация по английскому языку 45 урок Биболетова Українська мова. Діагностична робота

Українська мова. Діагностична робота