Translator: Knowledge and skills. Stages of the process of translation. Text processing knowledge and skills презентация

Содержание

- 2. Stages of translation Editing the source text Interpreting the source text Interpreting in target language Formulating

- 3. Editing the source text Is the study of the ST for the purpose of establishing its

- 4. Interpreting the source text Is an analysis-synthesis process at different language levels

- 5. Interpreting in target language Is transformulating a linguistic/ verbal text or its part after interpreting it

- 6. Formulating the translated text Is the stage of the translation process in which the translator chooses

- 7. Editing the translated text Is the final stage of the translation process. It is careful checking

- 8. Types of translation WRITTEN/ ORAL Pre-dictionary translation Formulation translation Instantaneous translation

- 9. Pre-dictionary translation Every translation is a pre-dictionary translation. This is the case when the translator of

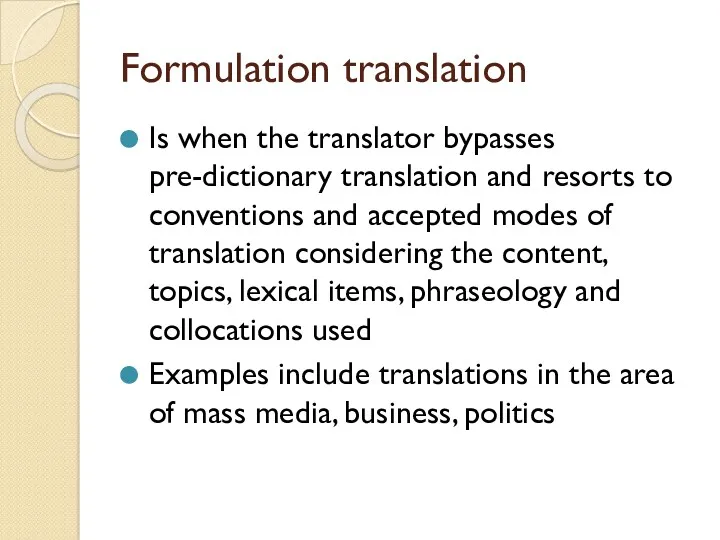

- 10. Formulation translation Is when the translator bypasses pre-dictionary translation and resorts to conventions and accepted modes

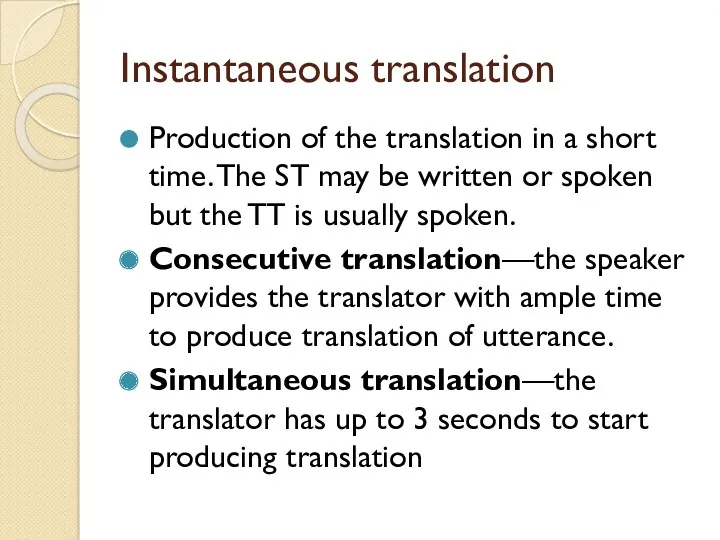

- 11. Instantaneous translation Production of the translation in a short time. The ST may be written or

- 12. IDEAL BILINGUAL COMPETENCE Ideal bilingual knows SL and TL perfectly and is unaffected by any external

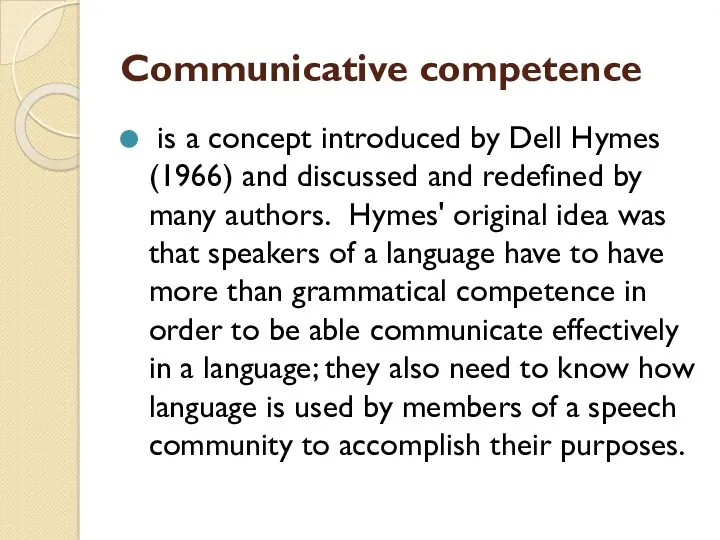

- 13. Communicative competence is a concept introduced by Dell Hymes (1966) and discussed and redefined by many

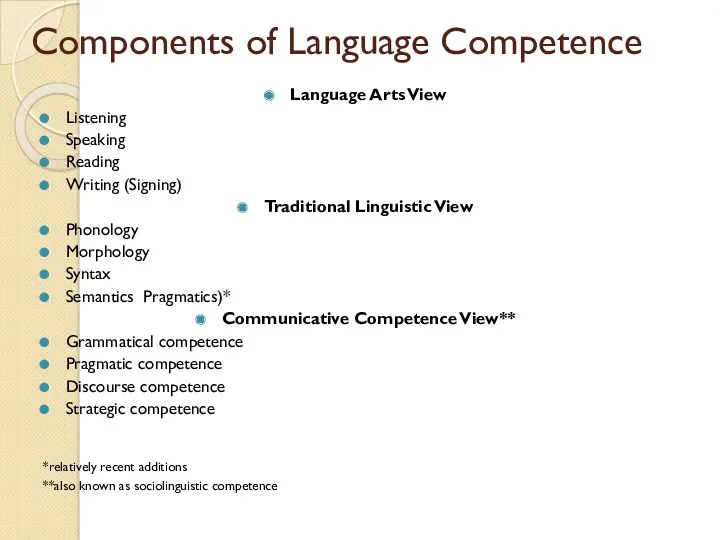

- 14. Components of Language Competence Language Arts View Listening Speaking Reading Writing (Signing) Traditional Linguistic View Phonology

- 15. Linguistic (Grammatical) Competence Linguistic Competence refers to the ability to use the language code or system

- 16. Pragmatic Competence Pragmatic Competence refers to the ability to use language appropriately in different social situations.

- 17. A. Language Functions The notion of function is commonly used in ELT textbooks and materials. We

- 18. For example, examine the uses of the imperative verb form Keep quiet! (order from a teacher)

- 19. B. Register Register is a term that relates to the words or expressions that are appropriate

- 20. Discourse Competence Discourse Competence refers to the way ideas are linked across sentences (in written discourse)

- 21. Strategic Competence Strategic Competence refers to a person’s ability to keep communication going when there is

- 22. Language Varieties The term language varieties refers to any form of a language—whether a regional or

- 23. Translation as a product refers to consideration of the text and discourse and their features

- 24. Text Is any verbalized communicative event performed via human language, no matter whether this communication is

- 25. Discourse is a complex communicative phenomenon which includes, besides the text itself, other factors of interaction

- 26. Text vs. discourse The text is a structured sequence of linguistic expressions forming a unitary whole,

- 27. Context the words that are used with a certain word or phrase and that help to

- 28. Types of contexts Macro context is the subject field world and the world in general Communicative

- 29. Contextual relationships Anaphoric /“backward” relationships. The meaning of an element becomes clear though the reference to

- 30. Text processing knowledge Two kinds of knowledge Procedural (knowing how to do smth.) Factual (knowing that

- 31. Three interlocking levels of linguistic knowledge Syntactic –limited to the means for creating clauses, the systems

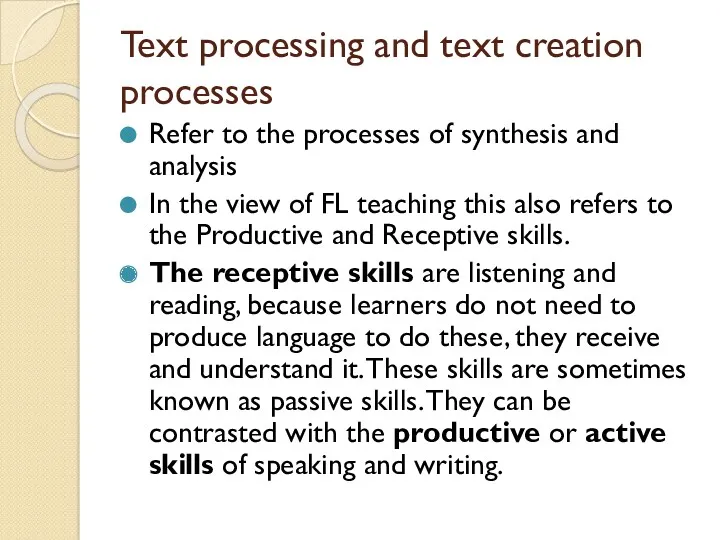

- 32. Text processing and text creation processes Refer to the processes of synthesis and analysis In the

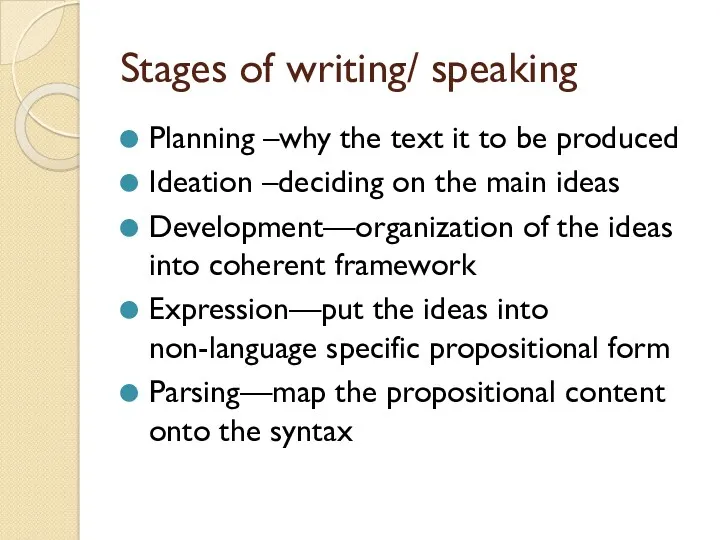

- 33. Stages of writing/ speaking Planning –why the text it to be produced Ideation –deciding on the

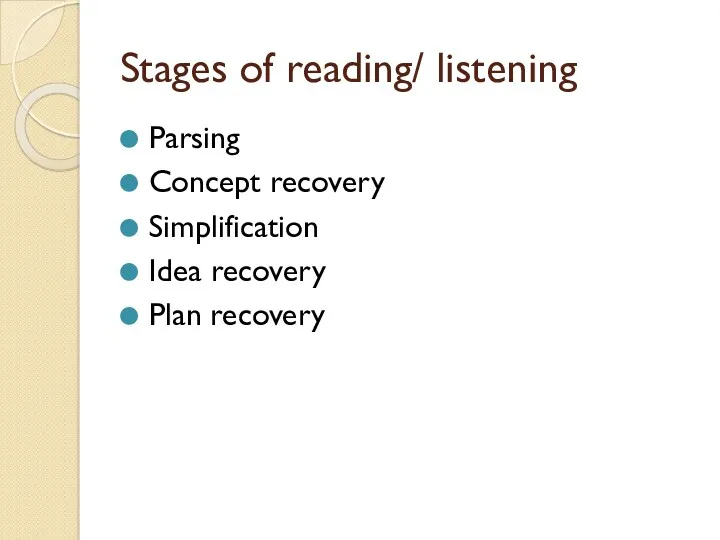

- 34. Stages of reading/ listening Parsing Concept recovery Simplification Idea recovery Plan recovery

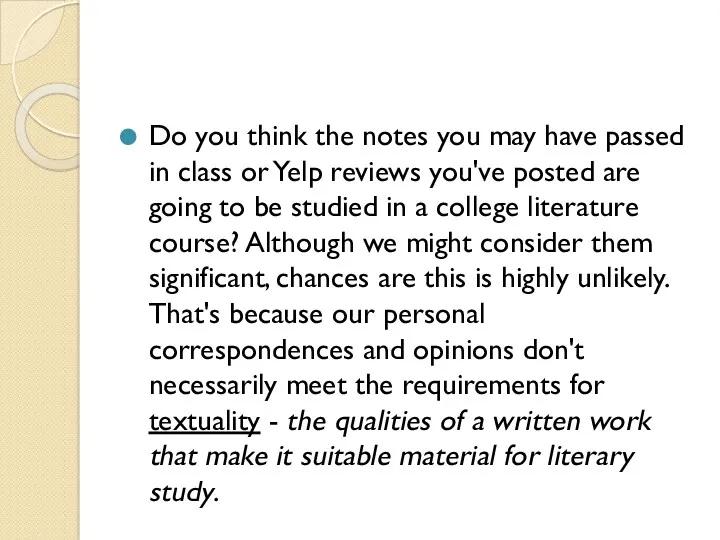

- 35. Do you think the notes you may have passed in class or Yelp reviews you've posted

- 36. The concept of textuality came about in the mid-20th century as a critical element in structuralism,

- 37. Barthes theorized that we can view literature through two different lenses: as a collection of 'works'

- 38. Regulative principles for the texts Efficiency—minimal efforts by the participants Effectiveness—success in creating the conditions for

- 39. “A text will be defined as a communicative occurrence which meets seven standards of textuality.”

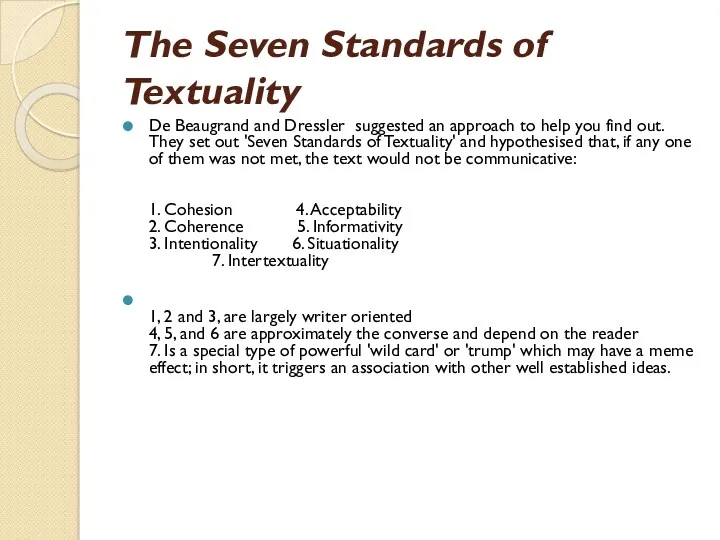

- 40. The Seven Standards of Textuality De Beaugrand and Dressler suggested an approach to help you find

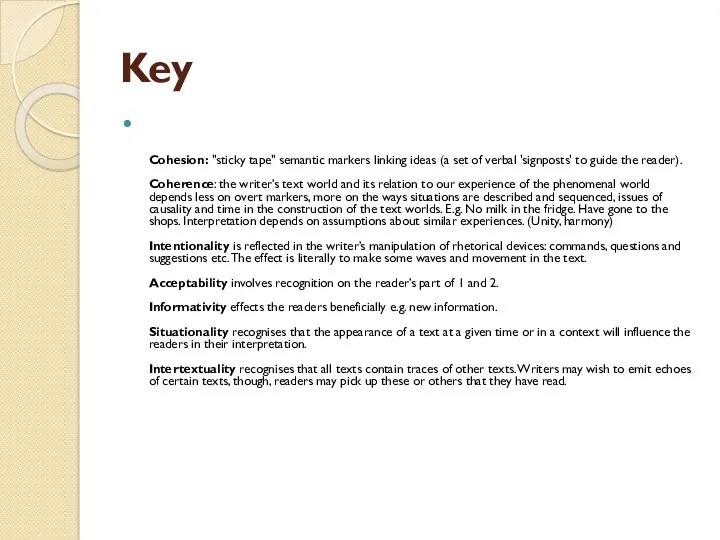

- 41. Key Cohesion: "sticky tape" semantic markers linking ideas (a set of verbal 'signposts' to guide the

- 42. Cohesion The first standard will be called cohesion and concerns the way in which the components

- 43. Cohesion is the network of lexical, grammatical, and other relations that provide links between various parts

- 44. Halliday and Hasan (1976) establish five cohesion categories: reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunctions, and lexical cohesion. In

- 45. Here, the two sentences, in each example, are linked to each other by a cohesive link.

- 46. In (b) My axe is blunt. I have to get a sharper one this relation is

- 47. In example (d) They fought a battle. Afterwards, it snowed none of the above relations exist;

- 48. Main cohesion category is called lexical cohesion (Halliday and Hasan) “There is a boy climbing the

- 49. Coherence coherence concerns the ways in which the components of the textual world, i.e. the configuration

- 50. Coherence: sub-surface feature concerns the ways in which the meanings within a text (concepts, relations among

- 51. Coherence The second standard will be called coherence and concerns the ways in which the components

- 52. Coherence Like cohesion, coherence is a network of relations which organise and create a text: cohesion

- 53. Cohesion and coherence are text-centred notions. "We will assume that cohesion is a property of the

- 54. Coherence Generally speaking, the mere presence of cohesive markers cannot create a coherent text; cohesive markers

- 55. The coherence of a text is a result of the interaction between knowledge presented in the

- 56. COHESION: A TEXT-LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE the way in which the components of the surface text, i.e. the

- 57. Inside the sentence, grammatical dependencies In the text cohesion is realized through the following: reference, substitution,

- 58. The other standards of textuality are user-centred notions.

- 59. Intentionality In addition, we shall require user-centered notions which are brought to bear on the activity

- 60. Intentionality While cohesion and coherence are to a large extent text-centred, intentionality is user-centred. A text-producer

- 61. Acceptability The fourth standard of textuality would be acceptability, concerning the text receiver’s attitude that the

- 62. Acceptability The receiver's attitude is that a text is cohesive and coherent. The reader usually supplies

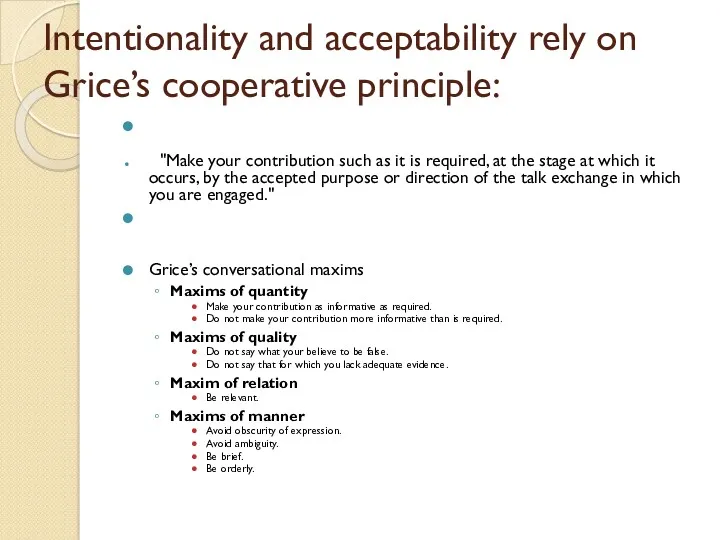

- 63. Intentionality and acceptability rely on Grice’s cooperative principle: "Make your contribution such as it is required,

- 64. Informativity The fifth standard of textuality is called informativity and concerns the extent to which the

- 65. Informativity A text has to contain some new information. A text is informative if it transfers

- 66. C. Shannon and W. Weaver's information theory (based on a statistic notion): the greater the number

- 67. syntactically probable, conceptually improbable: All our yesterdays have lighted fools to dusty death (Macbeth V v

- 68. Situationality The sixth standard of textuality can be designated situationality and concerns the factors which make

- 69. Situationality A text is relevant to a particular social or pragmatic context. Situationality is related to

- 70. Intertextuality The seventh standard is to be called intertextuality and concerns the factors which make the

- 71. Intertextuality A text is related to other texts. Intertextuality refers "to the relationship between a given

- 73. Скачать презентацию

презентация по теме Глобализация

презентация по теме Глобализация Види помилок в письмових роботах учнів

Види помилок в письмових роботах учнів Урок №1 немецкого языка во втором классе. Учебник Шаги Бим И.Л.

Урок №1 немецкого языка во втором классе. Учебник Шаги Бим И.Л. Становление фонематической стороны речи в онтогенезе

Становление фонематической стороны речи в онтогенезе Звуки [р] і [р']. Позначення їх буквами р и Р

Звуки [р] і [р']. Позначення їх буквами р и Р Засоби милозвучності української мови

Засоби милозвучності української мови Экзамены грядут

Экзамены грядут глагол to be в Past Simple глагол to be в Past Simple

глагол to be в Past Simple глагол to be в Past Simple Comparison of American and British Versions of English

Comparison of American and British Versions of English Специфіка синтаксичних характеристик наукового стилю

Специфіка синтаксичних характеристик наукового стилю Иксез-чиксез синең байлыгың

Иксез-чиксез синең байлыгың Интерактивный кроссворд Лексика сказок

Интерактивный кроссворд Лексика сказок Intercultural communication and technical translation department

Intercultural communication and technical translation department презентация на тему movement & action.

презентация на тему movement & action. La vie des jeunes en France

La vie des jeunes en France Урок по английскому языку по теме Здоровое питание

Урок по английскому языку по теме Здоровое питание Типология лексических систем английского и русского языков

Типология лексических систем английского и русского языков Проектная деятельность на уроках английского языка по личностно- ориентированной технологии

Проектная деятельность на уроках английского языка по личностно- ориентированной технологии Интерактивная презентация по теме Погода для 4 класса

Интерактивная презентация по теме Погода для 4 класса Ошибки в устной русской речи пятиязычных люксембурженок 6 и 8 лет

Ошибки в устной русской речи пятиязычных люксембурженок 6 и 8 лет учебное занятие The World of Hobbies 6 классУчебник: Английский с удовольствием /Enjoy English для 5-6 классов общеобразовательных учреждений

учебное занятие The World of Hobbies 6 классУчебник: Английский с удовольствием /Enjoy English для 5-6 классов общеобразовательных учреждений Степени сравнения прилагательных

Степени сравнения прилагательных Презентация по теме Притяжательный падеж существительных

Презентация по теме Притяжательный падеж существительных Презентация Menshikov Palace

Презентация Menshikov Palace Язык как знаковая система. Семиотика. (Лекция 3.2)

Язык как знаковая система. Семиотика. (Лекция 3.2) Ф.И.Тютчев в Мюнхене

Ф.И.Тютчев в Мюнхене Літературна мова і професійна діяльність військового. Тема 2

Літературна мова і професійна діяльність військового. Тема 2 Глагол в среднеанглийском языке

Глагол в среднеанглийском языке