Содержание

- 2. Attribution Theory deals with how the social perceiver uses information to arrive at causal explanations for

- 3. Attribution Theory Attribution theory, the approach that dominated social psychology in the 1970s. Attribution theory is

- 4. Heider (1958): ‘Naive Scientist’ Jones & Davis (1965): Correspondent Inference Theory Kelley (1973): Covariation Theory Theories

- 5. Errors Fundamental Attribution Error Ultimate Attribution Error Biases Self-serving bias Negativity bias Optimistic Bias Confirmation Bias

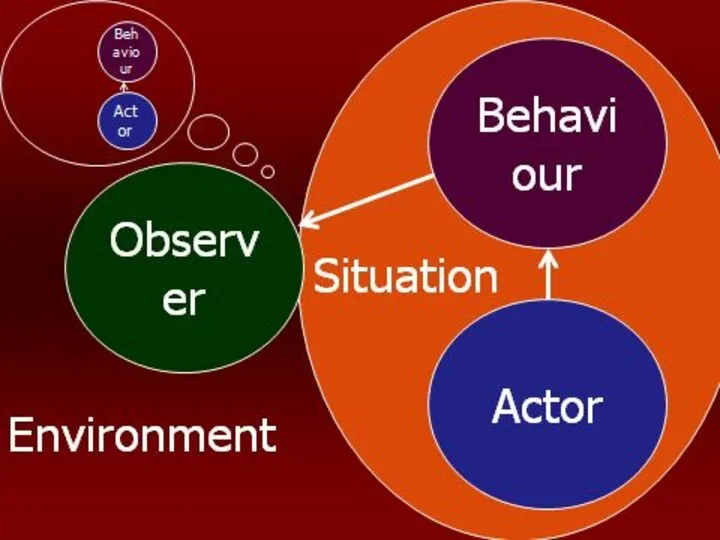

- 6. Tendency to attribute others’ behaviour to enduring dispositions (e.g., attitudes, personality traits) because of both: Underestimation

- 8. Explanations: Behavior is more noticeable than situational factors. People are cognitive misers. Richer trait-like language to

- 9. FAE applied to in- and out- groups Bias towards: internal attributions for in-group success and external

- 10. There is a pervasive tendency for actors to attribute their actions to situational requirements, whereas observers

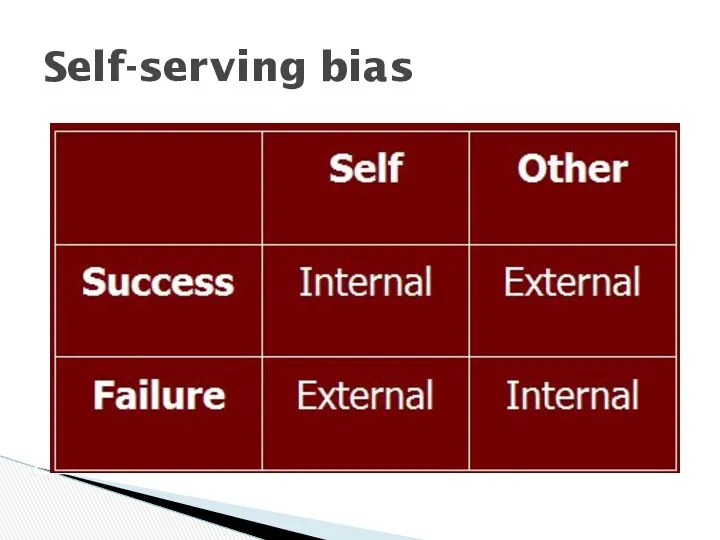

- 11. Self-serving bias

- 12. Motivational: Self-esteem maintenance. Social: Self-presentation and impression formation. Explanation of Self-serving bias

- 13. We pay more attention to negative information than positive information (often deliberately, sometimes automatically). NEGATIVITY BIAS

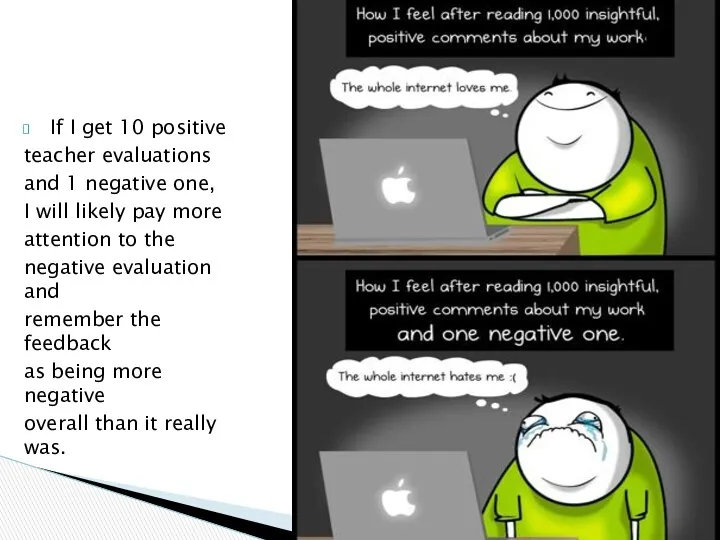

- 14. If I get 10 positive teacher evaluations and 1 negative one, I will likely pay more

- 15. Evolutionary Rationale Threats need to be dealt with ASAP EXPLANATIONS OF NEGATIVITY BIAS

- 16. The Optimistic Bias Believing that bad things happen to other people and that you are more

- 17. The Optimistic Bias (continued) Do you think you will be in a car accident this weekend?

- 18. The tendency to test a proposition by searching for evidence that would support it. CONFIRMATION BIAS

- 19. The tendency to test a proposition by searching for evidence that would support it. ○ If

- 20. The tendency to test a proposition by searching for evidence that would support it. ○ If

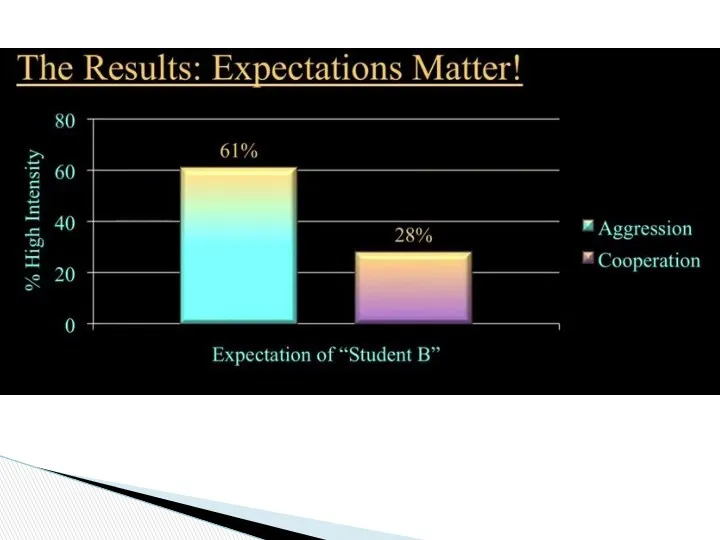

- 21. Snyder & Swann, 1978 ○ Introduced a person to the participants of the experiment ○ Had

- 22. When people were asked to determine if someone was introverted, asked questions like, “Do you enjoy

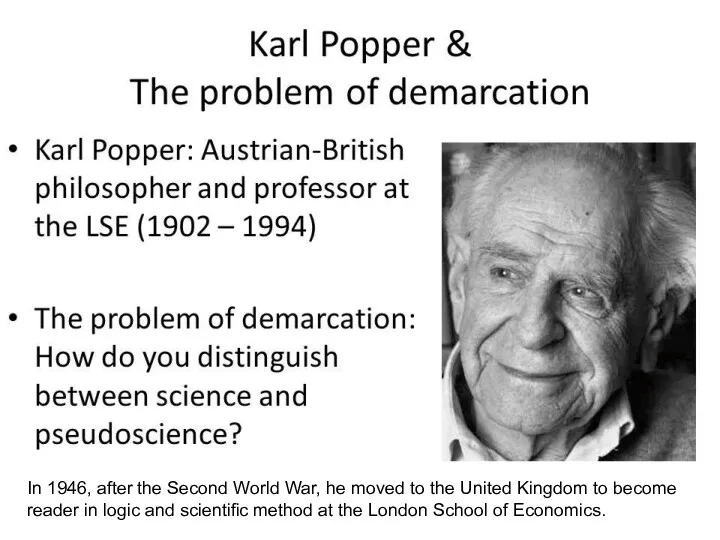

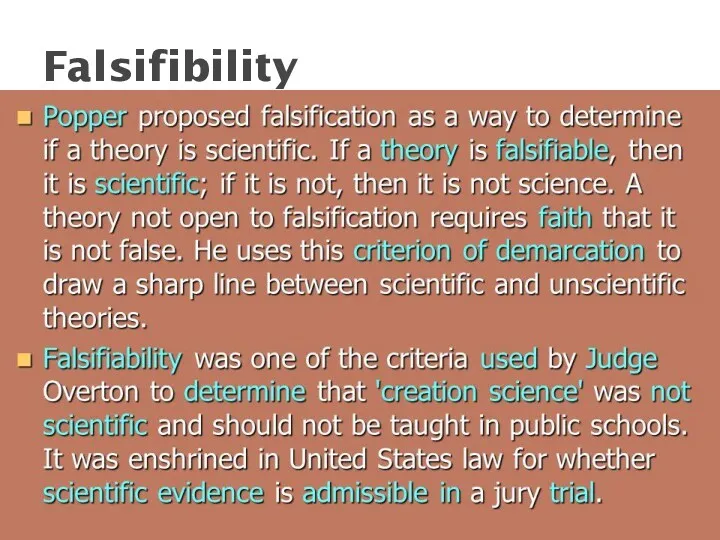

- 24. In 1946, after the Second World War, he moved to the United Kingdom to become reader

- 25. Falsifibility

- 26. Falsifibility

- 27. We remember schema-consistent information better than schema-inconsistent behavior. ● Because schemas influence attention, also influence memory.

- 28. Schemas Guide Attention ○ Attention is a limited resource. ○ We automatically allocate attention to relevant

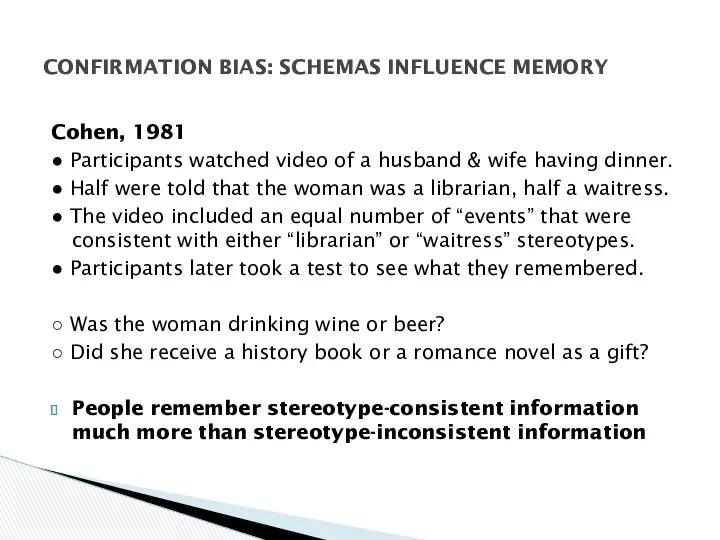

- 29. Cohen, 1981 ● Participants watched video of a husband & wife having dinner. ● Half were

- 30. Culture influence attribution processes. Social psychologists have widely studied the use of fundamental attribution error across

- 31. Individualist culture emphases the individual, and therefore, its members are predisposed to use individualist or dispositional

- 32. Causal Attribution Across Cultures Singh et al. (2003) studied the role of culture in blame attribution.

- 33. Causal Attribution Across Cultures Cross-cultural differences have been reported in the attribution of success and failure

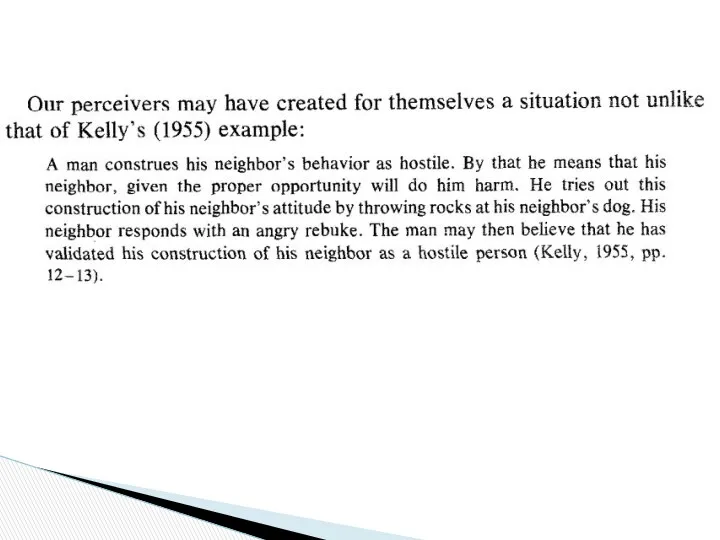

- 34. A self-fulfilling prophecy is a prediction that directly or indirectly causes itself to become true, by

- 35. Although examples of such prophecies can be found in literature as far back as ancient Greece

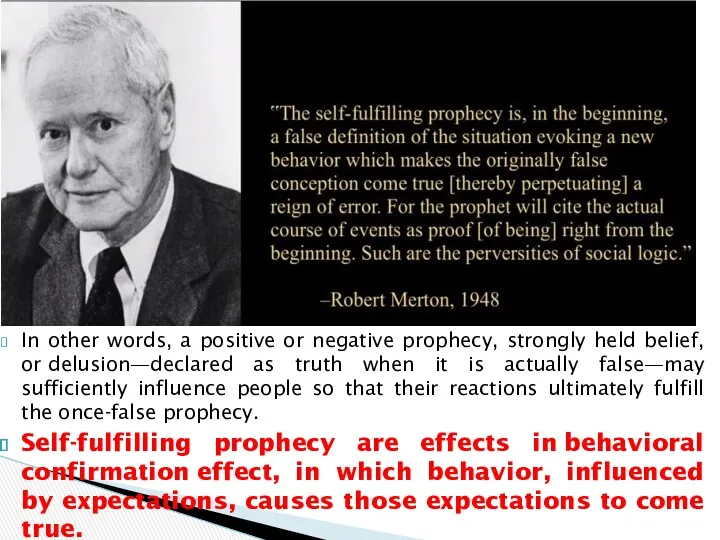

- 36. In other words, a positive or negative prophecy, strongly held belief, or delusion—declared as truth when

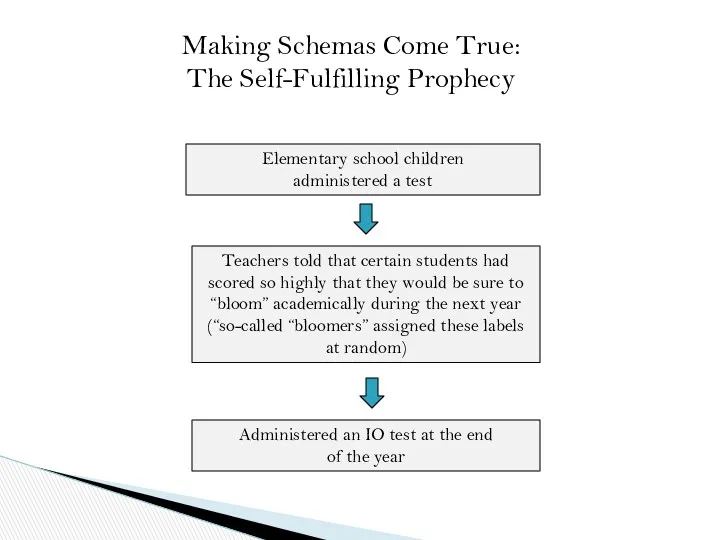

- 48. Making Schemas Come True: The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Elementary school children administered a test

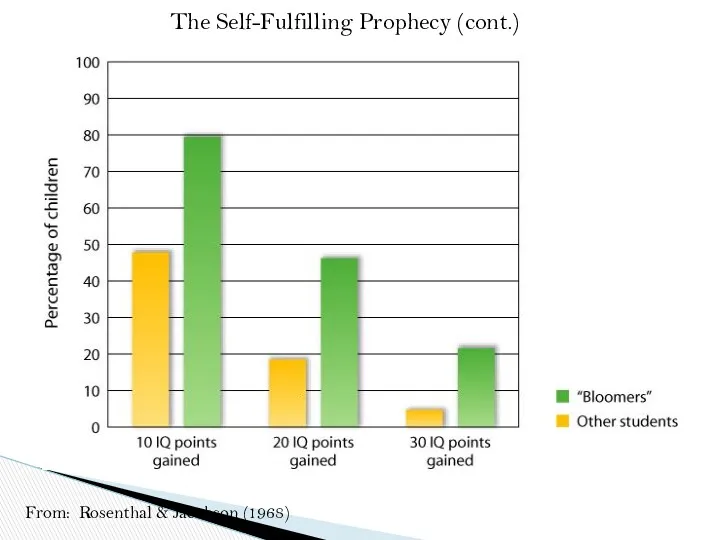

- 49. From: Rosenthal & Jacobson (1968) The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (cont.)

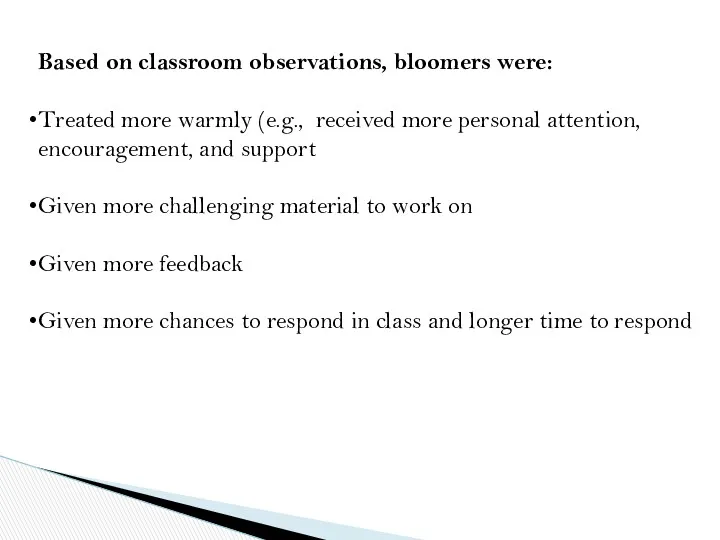

- 51. Based on classroom observations, bloomers were: Treated more warmly (e.g., received more personal attention, encouragement, and

- 52. Self-Fulfilling Prophecies A person "becomes" the stereotype that is held about them Selective filtering Paying attention

- 53. Heuristics: Mental shortcuts in social cognition

- 54. Heuristics are rules or principles that allow us to make social judgments more quickly and with

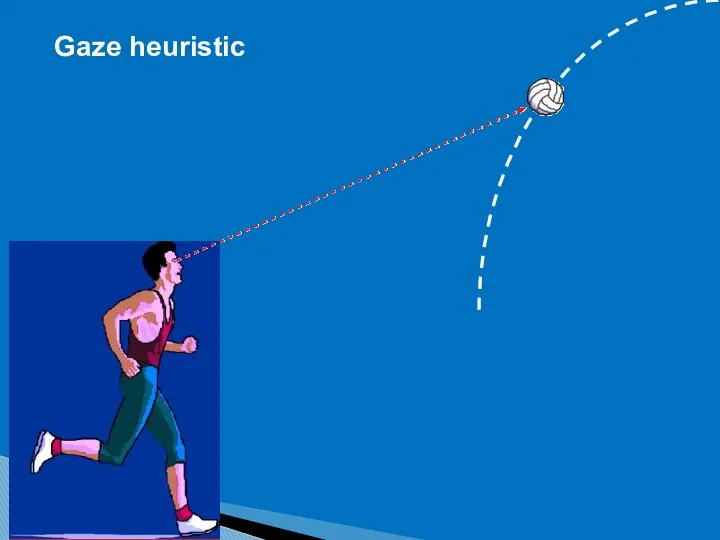

- 55. Experimental studies have shown that if people ignore the fact they were solving a system of

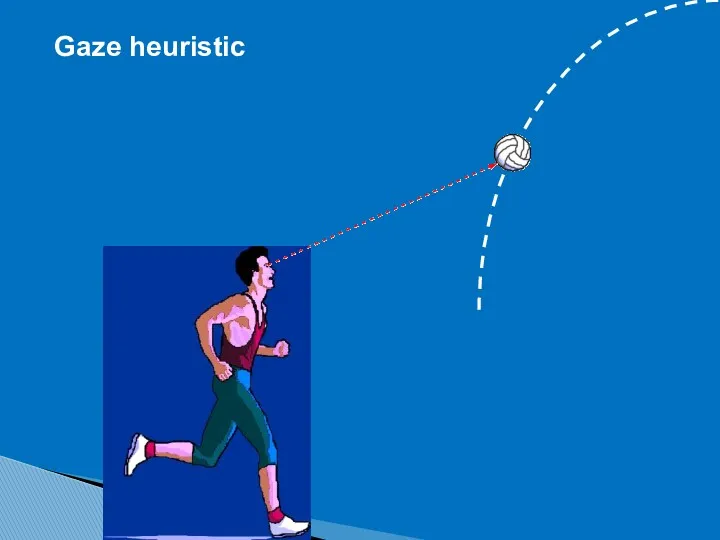

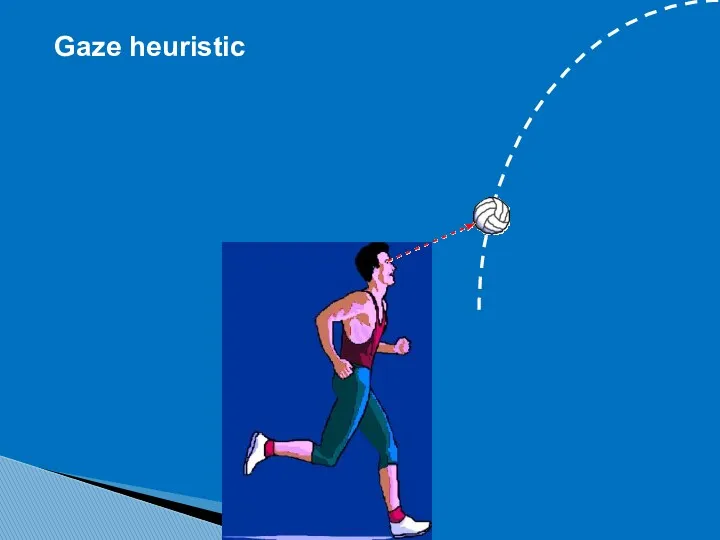

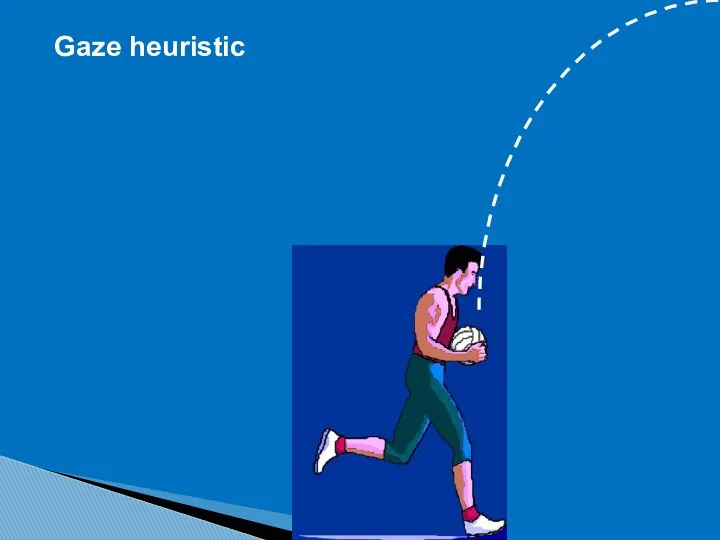

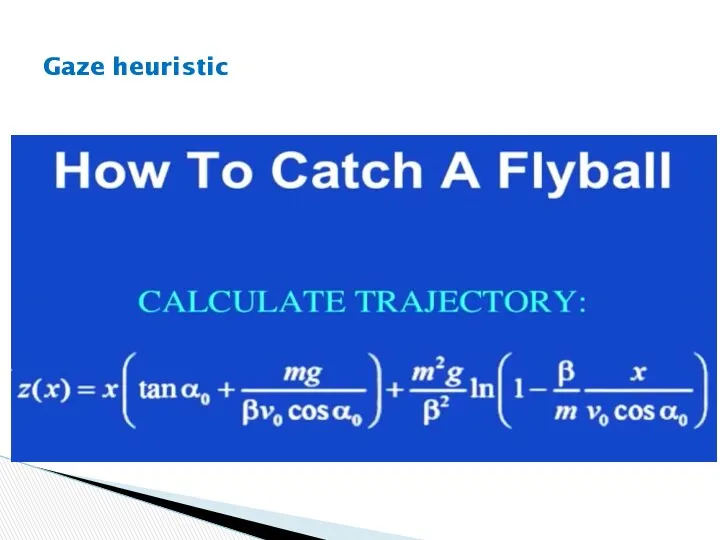

- 56. Gaze heuristic

- 57. Gaze heuristic

- 58. Gaze heuristic

- 59. Gaze heuristic

- 60. Gaze heuristic

- 61. The gaze heuristic is a heuristic used in directing correct motion to achieve a goal using

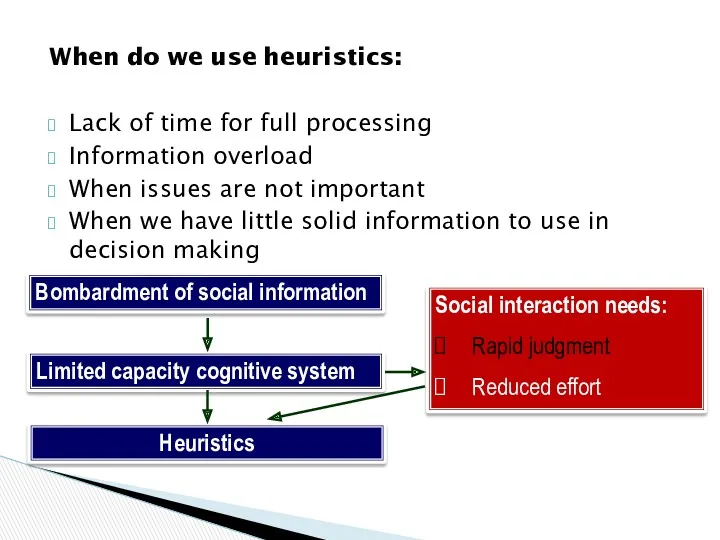

- 62. When do we use heuristics: Lack of time for full processing Information overload When issues are

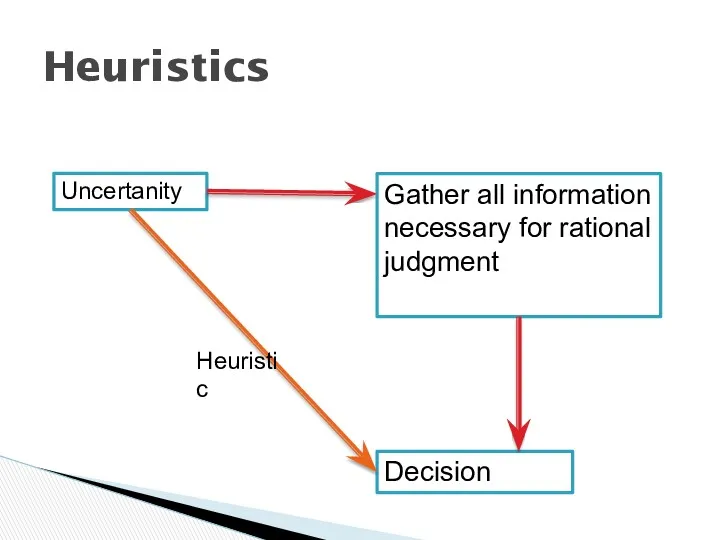

- 63. Heuristics Uncertanity Gather all information necessary for rational judgment Decision Heuristic

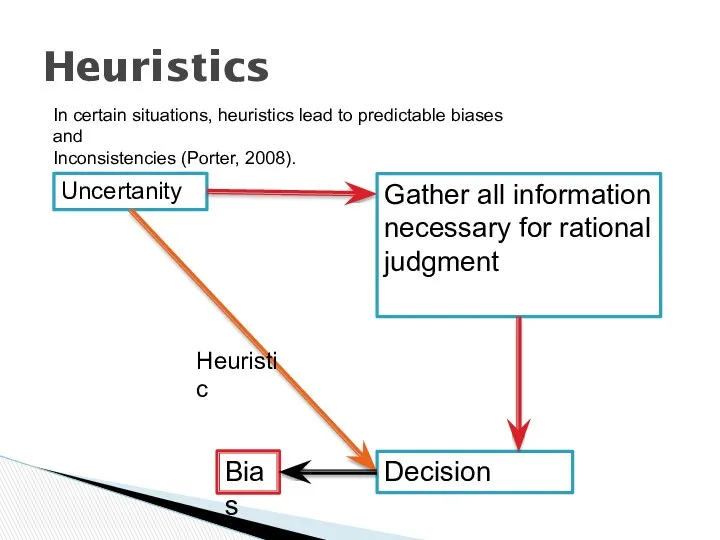

- 64. Heuristics Uncertanity Gather all information necessary for rational judgment Decision Heuristic In certain situations, heuristics lead

- 65. The most famous/popular heuristics: 1. Availability Heuristic 2. Representativeness Heuristic 3. Simulation Heuristic HEURISTICS

- 66. What comes to mind first: “If I think of it, it must be important” Suggests that,

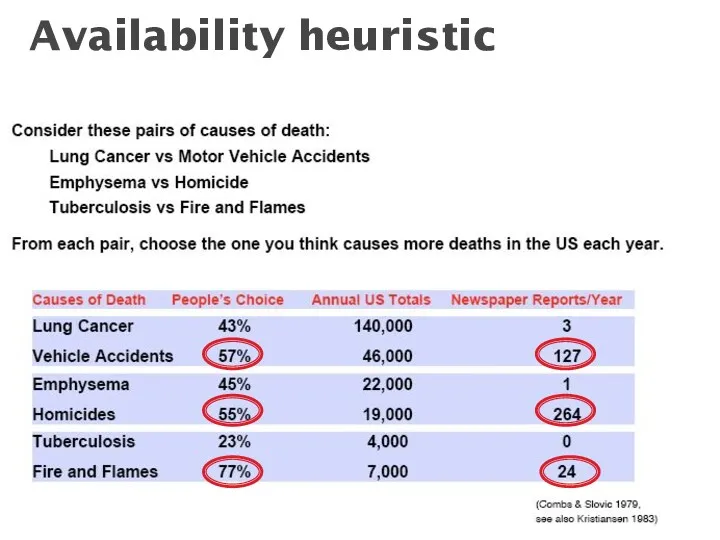

- 67. Availability heuristic The availability heuristic is a phenomenon (which can result in a cognitive bias) in

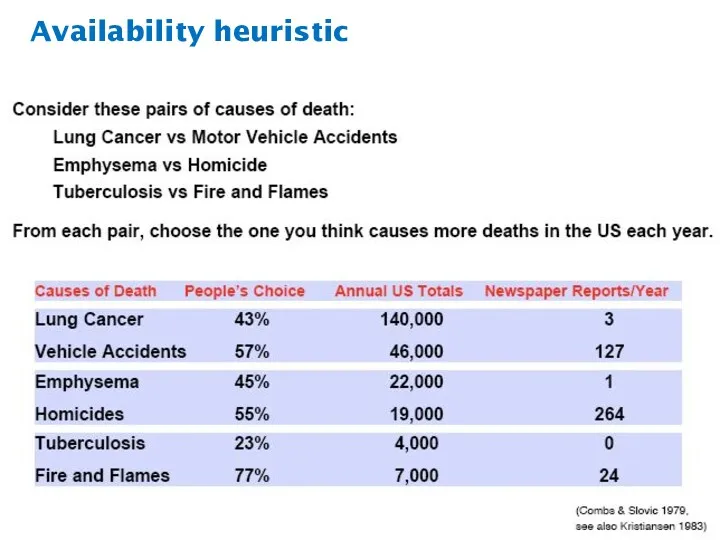

- 68. Availability heuristic

- 69. Availability heuristic

- 70. ○ Group Projects ● Because you worked on your portion of a group project, it’s easy

- 71. Marriage & Chores (Ross & Sicoly, 1979) ● Married couples were asked to give the percentage

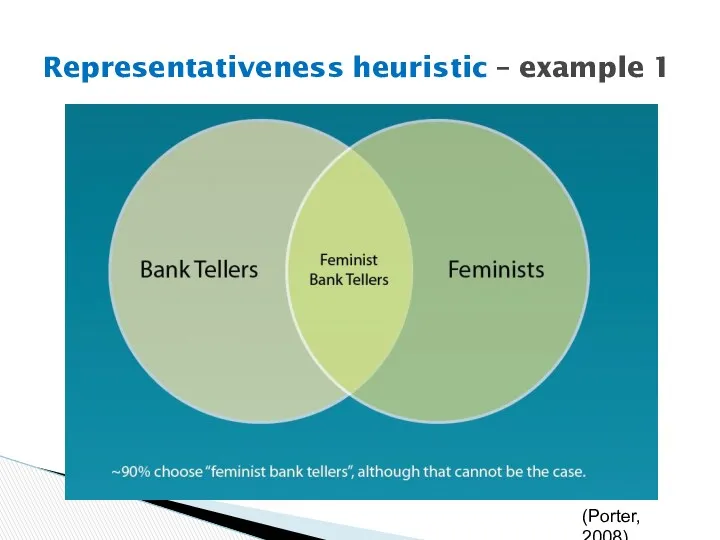

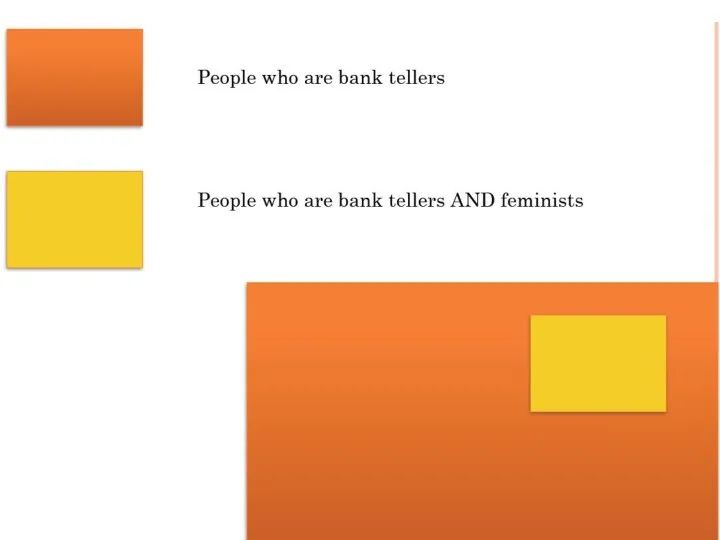

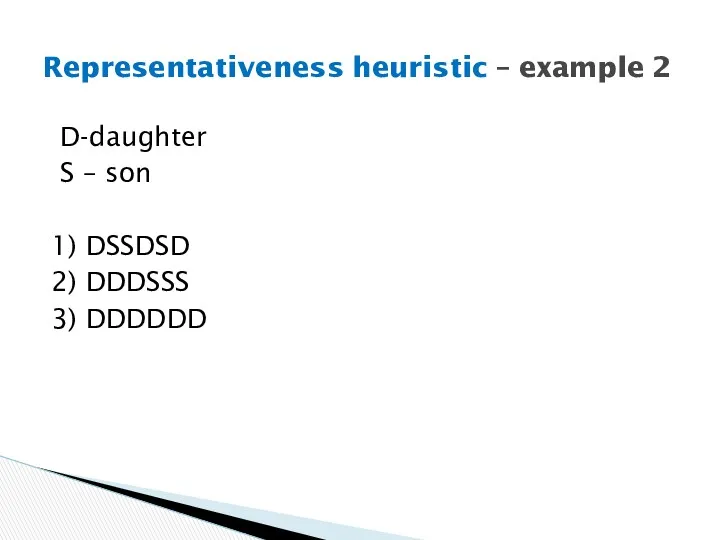

- 72. The tendency to judge frequency or likelihood of an event by the extent to which it

- 74. Representativeness heuristic – example 1 (Porter, 2008)

- 76. D-daughter S – son 1) DSSDSD 2) DDDSSS 3) DDDDDD Representativeness heuristic – example 2

- 77. A third kind of heuristic is the simulation heuristic, which is defined by the ease of

- 78. Example I. "Mr. Crane and Mr. Tees were scheduled to leave the airport on different flight

- 79. So people mentally simulate the event. If it seems easer to undo, then it is more

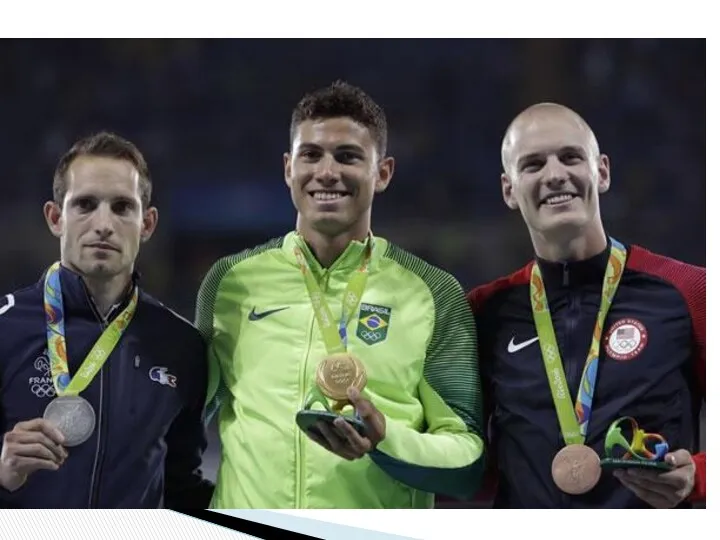

- 80. Example II: In the Olympics, bronze medalists appear to be happier than silver medalists, because it

- 85. Counterfactual Thinking Imagining different outcomes for an event that has already occurred Is usually associated with

- 86. Counterfactual Thinking Upward counterfactuals “If only I had bet on the winning horse!" "If only I’d

- 87. Counterfactual Thinking Downward counterfactuals "I got a C on the test, but at least it’s not

- 89. Скачать презентацию

Эффективная (конструктивная) критика

Эффективная (конструктивная) критика Формирование оценки собственной деятельности обучающимися через приемы рефлексии

Формирование оценки собственной деятельности обучающимися через приемы рефлексии Особенности профессионального общения медика

Особенности профессионального общения медика Концепция развития психологической службы в системе образования в Российской Федерации

Концепция развития психологической службы в системе образования в Российской Федерации Теории личности в зарубежной психологии: краткий обзор

Теории личности в зарубежной психологии: краткий обзор Введение в профессию психолог

Введение в профессию психолог Ел болашағы. Шылау сөздер

Ел болашағы. Шылау сөздер Конфликты и способы их преодоления

Конфликты и способы их преодоления Как следует говорить и слушать. Риторика и речевое поведение человека

Как следует говорить и слушать. Риторика и речевое поведение человека Индивидуально-психологические особенности руководителя

Индивидуально-психологические особенности руководителя Оқушылардың өзін - өзі тануы және өзін - өзі дамытуы педагогикалық қолдау қазіргі білім беру миссиясы

Оқушылардың өзін - өзі тануы және өзін - өзі дамытуы педагогикалық қолдау қазіргі білім беру миссиясы Проблемы специальной психологии и психологии аномального развития

Проблемы специальной психологии и психологии аномального развития Мультимедийная разработка психологического занятия

Мультимедийная разработка психологического занятия Способности. Природа человеческих способностей

Способности. Природа человеческих способностей Анализ социально-психологических особенностей пожилых людей

Анализ социально-психологических особенностей пожилых людей Основные методы, использующиеся в ходе тренинговых занятий

Основные методы, использующиеся в ходе тренинговых занятий Спор, дискуссия, конфликт

Спор, дискуссия, конфликт Убеждающее сообщение

Убеждающее сообщение Психология познания. Воображение. (Тема 5)

Психология познания. Воображение. (Тема 5) Conflict. What is conflict. Sources of conflict. Types of conflict. Ways out of the conflict

Conflict. What is conflict. Sources of conflict. Types of conflict. Ways out of the conflict Психоанализ. Зигмунд Фрейд

Психоанализ. Зигмунд Фрейд Поддержка старшеклассников при сдаче ЕГЭ

Поддержка старшеклассников при сдаче ЕГЭ Общение и источники преодоления обид

Общение и источники преодоления обид Позиции в общении: трансактный анализ Э.Бёрна

Позиции в общении: трансактный анализ Э.Бёрна Родительское собрание Профилактика употребления вредных веществ среди подростков

Родительское собрание Профилактика употребления вредных веществ среди подростков Прикладная экспериментальная психология и психофизика

Прикладная экспериментальная психология и психофизика Классный час: Одиночество – одна из причин жизненных затруднений

Классный час: Одиночество – одна из причин жизненных затруднений История становления психологической службы во Франции

История становления психологической службы во Франции