Содержание

- 2. Cossacks The name Cossack is derived from the Turkic kazak (free man), meaning anyone who could

- 3. The history of the Ukrainian Cossacks has three distinct aspects:

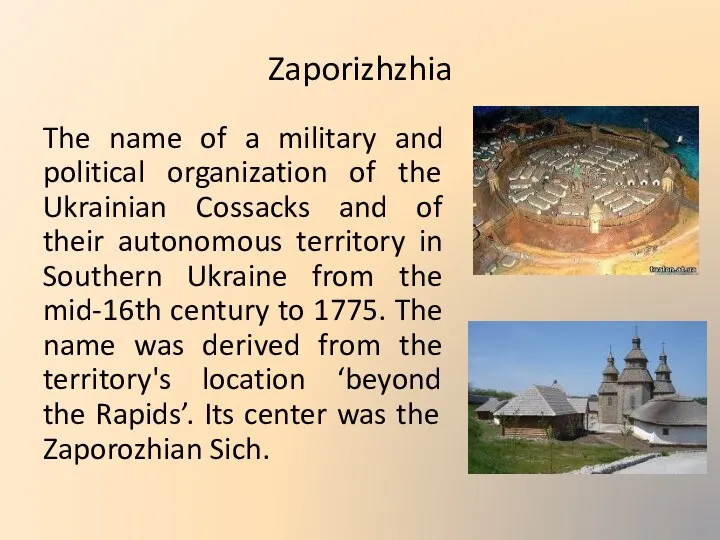

- 4. Zaporizhzhia The name of a military and political organization of the Ukrainian Cossacks and of their

- 5. Brotherhoods Fraternities affiliated with private churches in the Ukraine that performed religious and secular functions. Brotherhoods

- 6. The Ukrainian brotherhoods assumed the task of defending the Orthodox faith and Ukrainian nationality. The schools

- 7. The first schools The first school was established in 1586 by the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood. The

- 8. Studies At first the brotherhood schools adopted the structure and curriculum of the Jesuit schools, using

- 9. Brotherhood schools made a significant contribution to the growth of religious and national consciousness and the

- 10. The Ostrih Academy Founded in 1576 in Ostrih, Volhynia, by a Ukrainian nobleman kniaz Ostrozky –

- 11. The curriculum consisted of Church Slavonic, Greek, Latin, theology, philosophy, medicine, natural science, and the classical

- 12. Kyiv-Mohyla Academy The Academy was first opened in 1615 as the school of the Kyiv brotherhood.

- 13. The Academy educated Ukrainian political and intellectual elite in the 17th and 18th centuries, and it

- 14. Hetmans – leaders of Zaporozhzhian Cossacs - actively supported the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. The school flourished under

- 15. Printing The earliest books printed in the Ukrainian redaction of Church Slavonic and in the Cyrillic

- 16. Ivan Fedorov The first printing press on Ukrainian territory was founded by Ivan Fedorov in Lviv

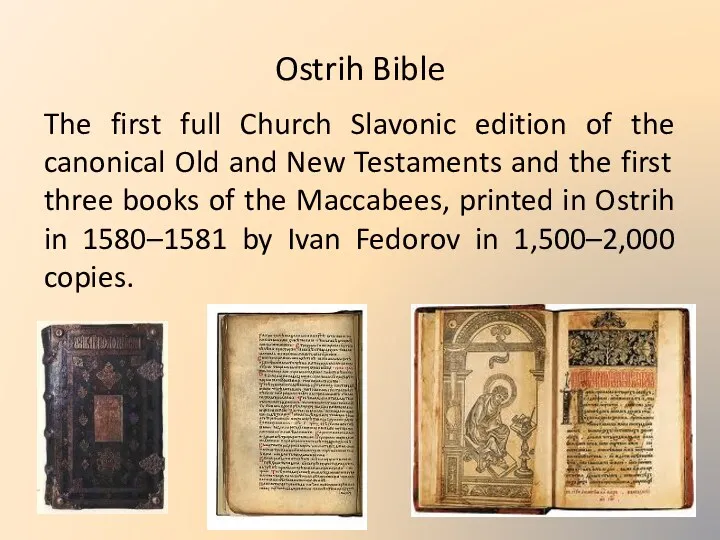

- 17. Ostrih Bible The first full Church Slavonic edition of the canonical Old and New Testaments and

- 18. In Kyiv, printing began with the founding of the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press (1615-1918). In Left-Bank

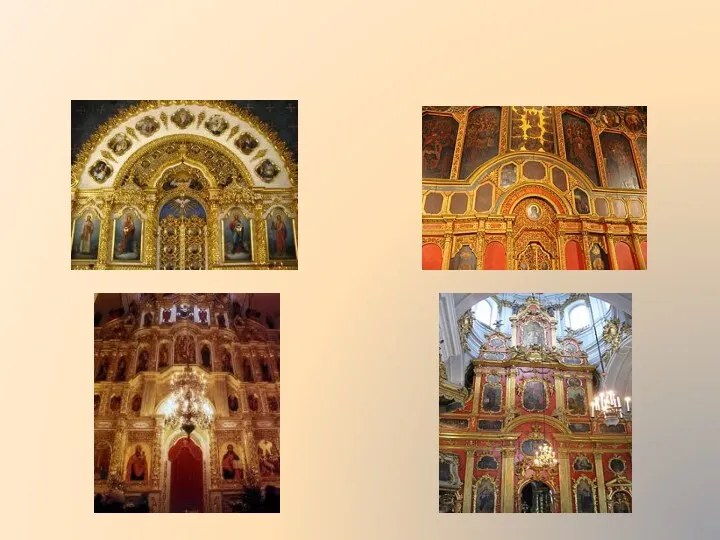

- 19. 2. Architecture Ukrainian Baroque or Cossack Baroque is an architectural style that emerged in Ukraine during

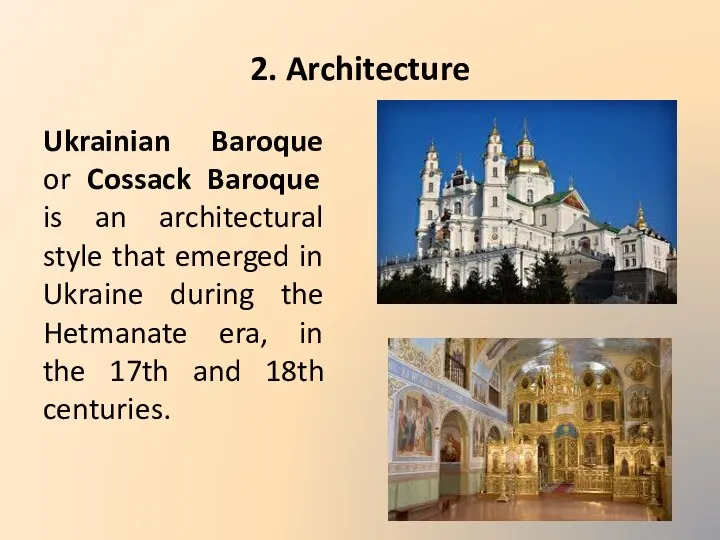

- 20. The works of the period, particularly the architectural works, are marked by rich, flamboyant forms, filled

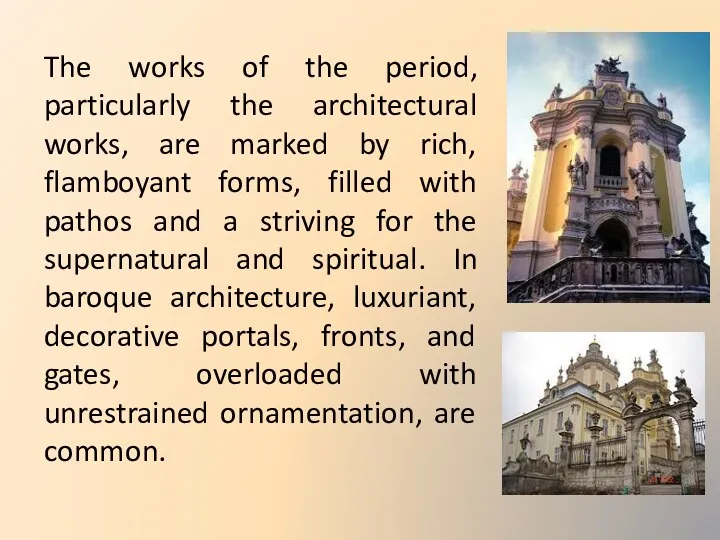

- 21. Features of Baroque Art:

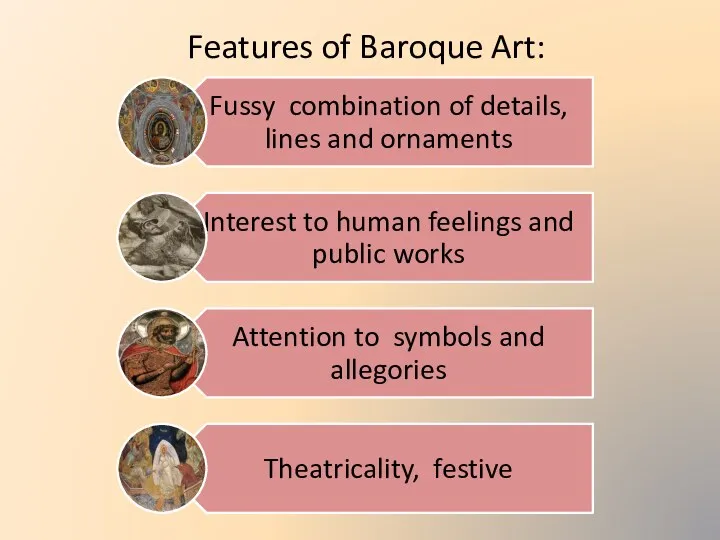

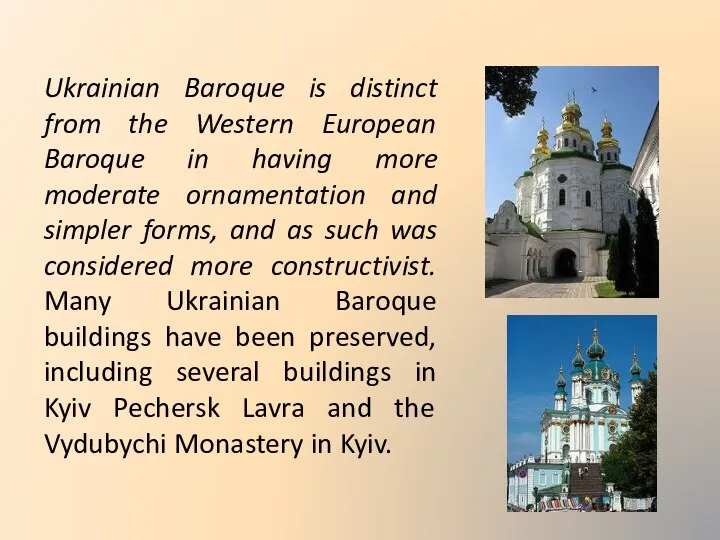

- 22. Ukrainian Baroque is distinct from the Western European Baroque in having more moderate ornamentation and simpler

- 23. Vydubychi Monastery in Kyiv

- 24. Baroque painting The best examples of Baroque painting are the church paintings in the Holy Trinity

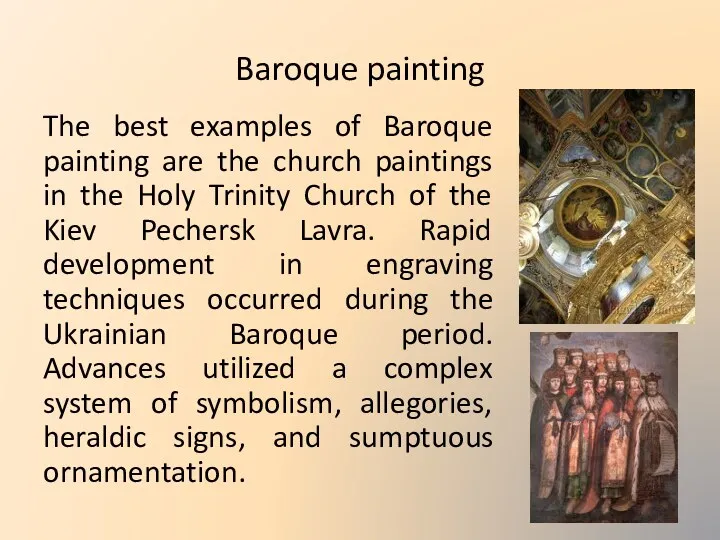

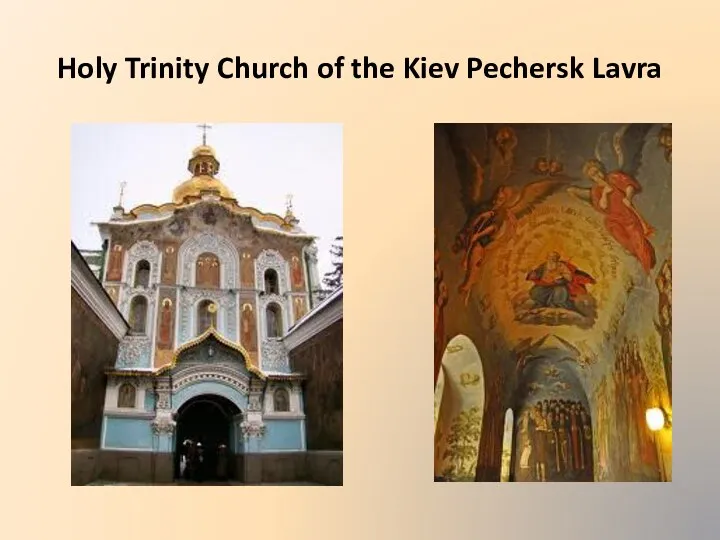

- 25. Holy Trinity Church of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra

- 26. Icon The paint—an emulsion of mineral pigments, egg yolk, and water—is applied with a brush to

- 27. Masters In the 16th century Lviv became the main center of icon painting. The names of

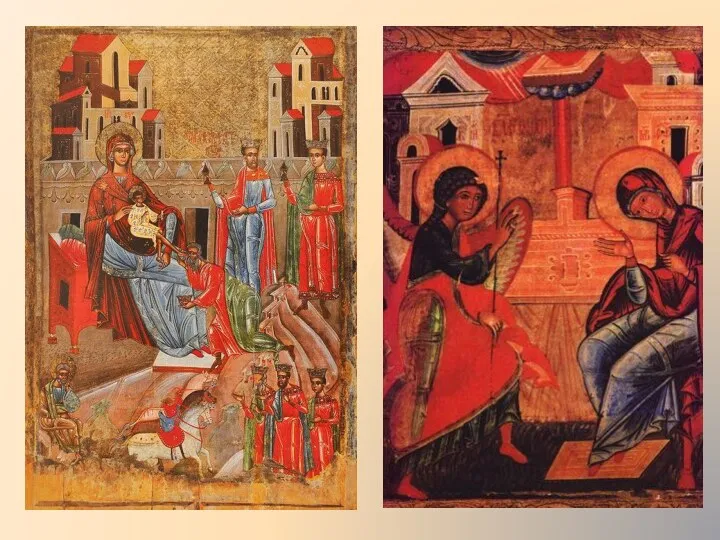

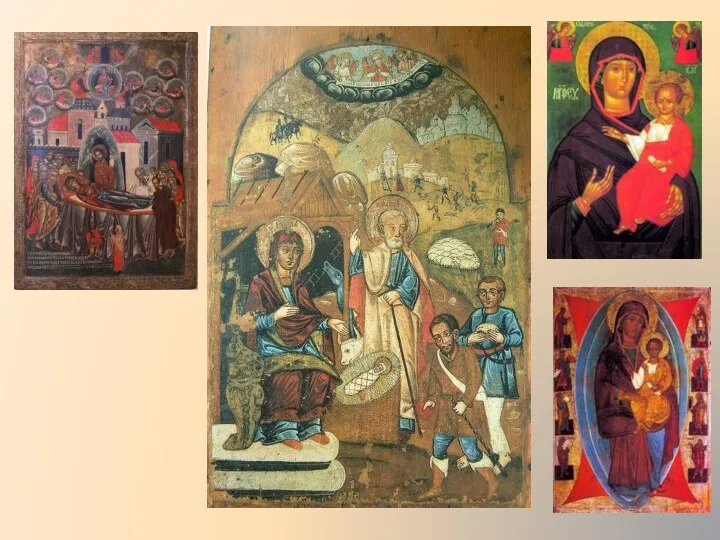

- 28. The Style The style evolved towards a greater emphasis of the graphic element, which became typical

- 29. The colors became livelier. The background was colored solid gold or silver and was ornamented with

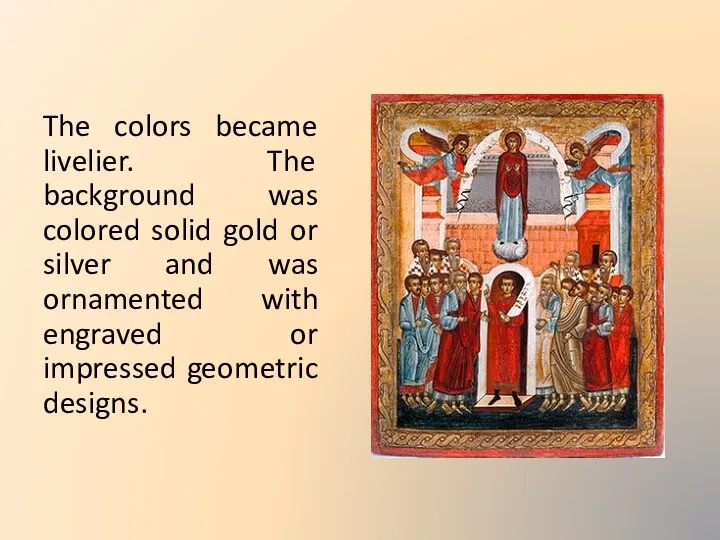

- 30. The chief icon painting schools in Galicia were those of Peremyshl and Lviv. Each of them

- 31. The finest samples: The Nativity of Christ from Trushevychi, The Annunciation from Dalova, The Dormition of

- 34. Icon in the Eastern Ukraine At the beginning of the 17th century icon painting began to

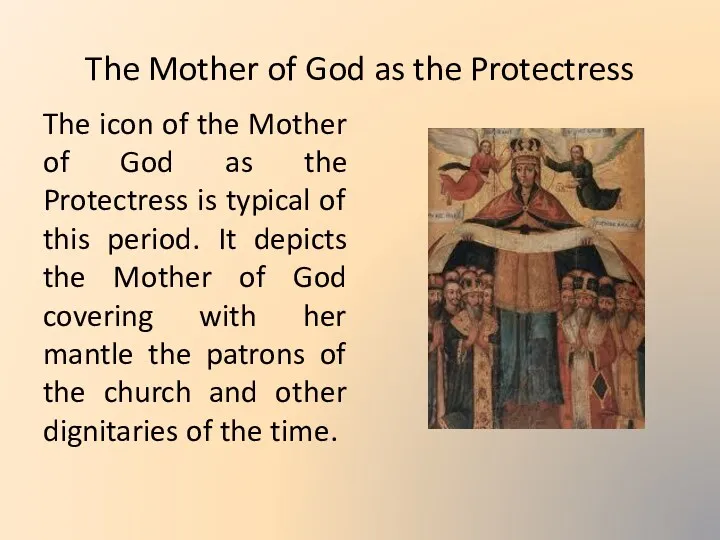

- 36. The Mother of God as the Protectress The icon of the Mother of God as the

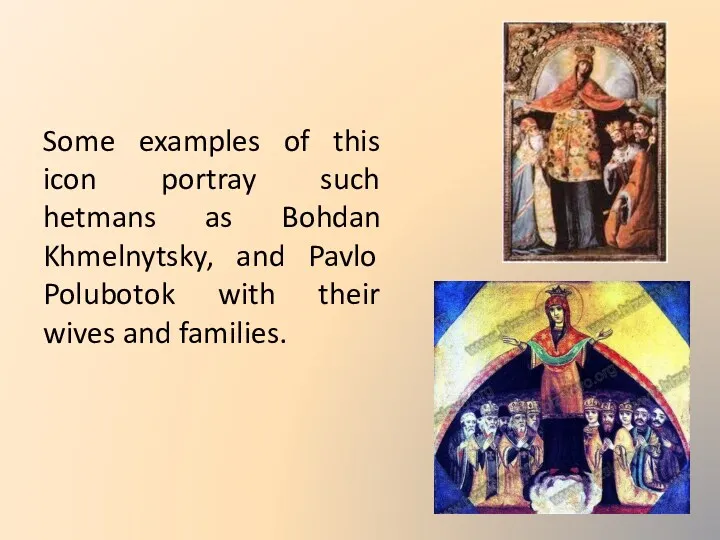

- 37. Some examples of this icon portray such hetmans as Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and Pavlo Polubotok with their

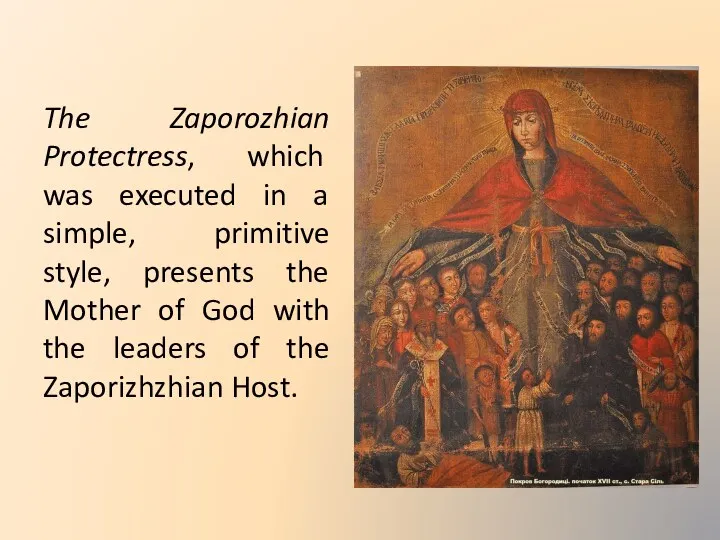

- 38. The Zaporozhian Protectress, which was executed in a simple, primitive style, presents the Mother of God

- 39. By the second half of the 18th century the icon evolved into an ordinary painting on

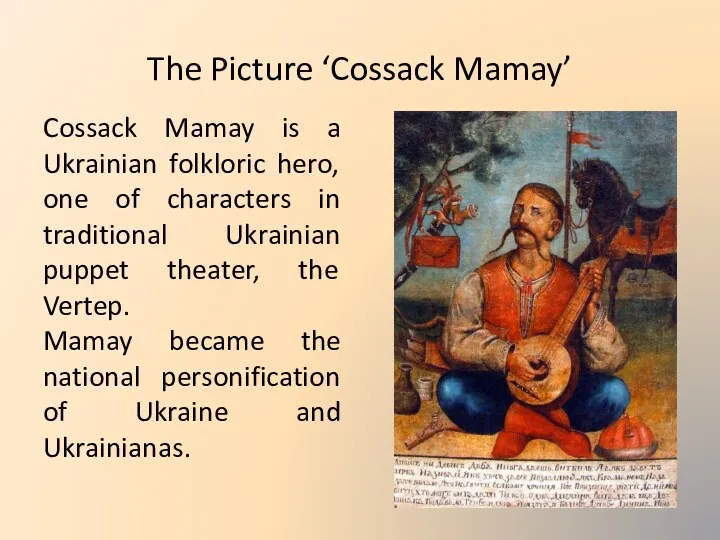

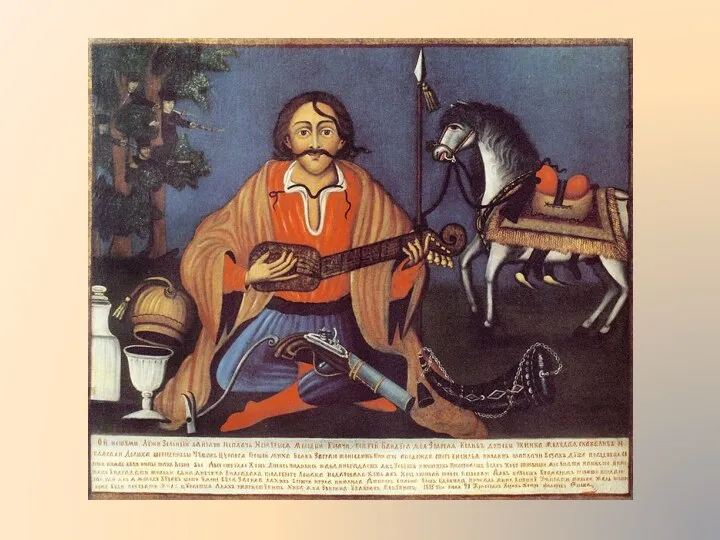

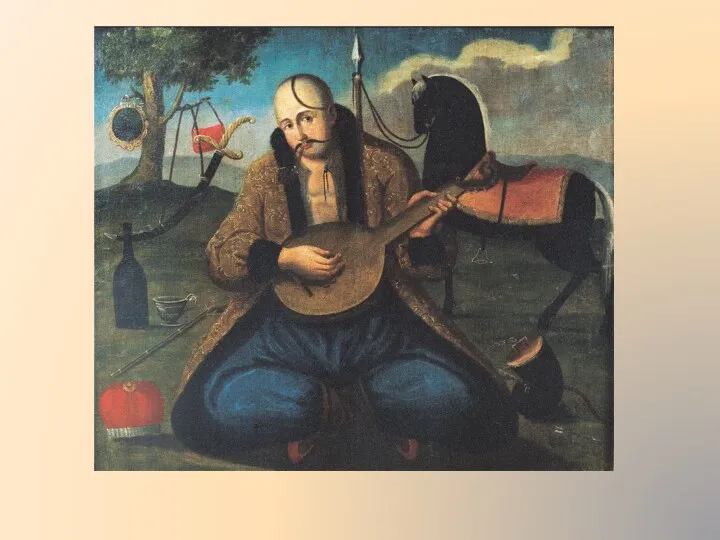

- 40. The Picture ‘Cossack Mamay’ Cossack Mamay is a Ukrainian folkloric hero, one of characters in traditional

- 41. These picture became widely popular after the dissolution of the Zaporizhzhian Sich in 1775. In the

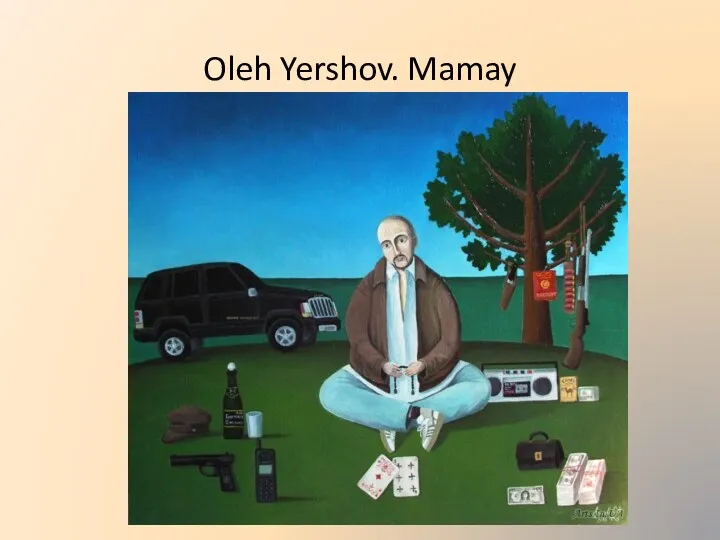

- 44. Oleh Yershov. Mamay

- 45. 3. Literature In Ukraine and Belarus polemical literature dates back to the religious denominational struggles of

- 46. Ivan Vyshenskyj Ivan Vyshenskyj (1550– after 1620) - Ukrainian writer, orthodox monk and religious philosopher, author

- 47. Hryhorij Skovoroda (1722–1794) Brought up in a spirit of philosophical and religious studies, he became an

- 48. "Our kingdom is within us - he wrote - and to know God, you must know

- 49. "Belief in God does not mean - belief in his existence - and therefore to give

- 50. "Sanctity of life lies in doing good to people"

- 51. Works Skovoroda wrote collection of 30 verses (1753-1785) titled ‘Sad bozhestvennykh pesnei’ (Garden of Divine Songs),

- 52. Ivan Kotliarevs’ky Kotliarevs’ky Ivan (1769-1838) – poet and playwright; the ‘founder’ of modern Ukrainian literature. His

- 53. Aeneid The poem ‘Aeneid’ was written at a time when popular memory of the Cossack Hetmanate

- 55. Скачать презентацию

Арабы в VI - VII веках. Возникновение ислама

Арабы в VI - VII веках. Возникновение ислама Восточная Европа во второй половине XX века

Восточная Европа во второй половине XX века Движение Алаш и казахская национальная идея. Личность Алихана Бокейханова

Движение Алаш и казахская национальная идея. Личность Алихана Бокейханова Объекты Всемирного культурного наследия в России

Объекты Всемирного культурного наследия в России Вавилонский царь Хамураппи и его законы

Вавилонский царь Хамураппи и его законы Движение декабристов. Урок истории. 10 класс

Движение декабристов. Урок истории. 10 класс Путешественники и их открытия

Путешественники и их открытия Духовная жизнь СССР в 20-30 годы

Духовная жизнь СССР в 20-30 годы Серебряный век русской культуры

Серебряный век русской культуры Использование проектной технологии на уроках истории и во внеурочной деятельности

Использование проектной технологии на уроках истории и во внеурочной деятельности Древний Египет

Древний Египет Внутренняя политика Александра І в 1812-1825 гг

Внутренняя политика Александра І в 1812-1825 гг Балашиха в годы Великой Отечественной войны

Балашиха в годы Великой Отечественной войны Борьба Шотландии за независимость. Эдуард I, Уильям Уоллес, Роберт Брюс

Борьба Шотландии за независимость. Эдуард I, Уильям Уоллес, Роберт Брюс Внешняя политика Российского государства в I трети XVI века. На юго-восточных границах

Внешняя политика Российского государства в I трети XVI века. На юго-восточных границах Жапония

Жапония Культура Византии

Культура Византии Первая мировая война 1914-1918 гг

Первая мировая война 1914-1918 гг Новые учебники истории: взгляд педагога-практика на содержательную и методическую составляющие

Новые учебники истории: взгляд педагога-практика на содержательную и методическую составляющие Великая греческая колонизация. (Тема 5)

Великая греческая колонизация. (Тема 5) Презентация по истории Герои Русской истории

Презентация по истории Герои Русской истории Первая мировая война. 1914 - 1918 гг. Начало

Первая мировая война. 1914 - 1918 гг. Начало Культура Древней Греции

Культура Древней Греции История как наука

История как наука Отечественная война 1812

Отечественная война 1812 В борьбе за единство и независимость. Эпоха Куликовской битвы

В борьбе за единство и независимость. Эпоха Куликовской битвы Дистанционное обучение как способ формирования ключевых компетенций

Дистанционное обучение как способ формирования ключевых компетенций Петрозаводск

Петрозаводск