Содержание

- 2. Key questions Why did ‘settler colonialism’ take root in the territories of modern day Kazakhstan in

- 3. Factors contributing to the rise of settler colonialism PART I

- 4. What is ‘settler colonialism’? The population of England (w/o Scotland and Ireland) doubled from 8.3 million

- 5. Images of 19th century Irkutsk ‘The resettlement [pereselenie] of state peasants has twin purposes: a) so

- 6. What role did the Tsarist state play in encouraging migration across Urals? July 1889: statute authorising

- 7. What was the importance of non-state actors in encouraging migration? Khodoki Numbers of unofficial migrants difficult

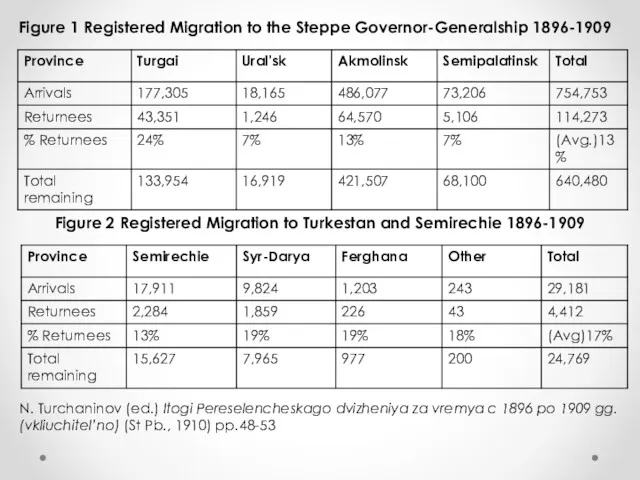

- 8. Figure 1 Registered Migration to the Steppe Governor-Generalship 1896-1909 Figure 2 Registered Migration to Turkestan and

- 9. What made mass migration possible? Bridge over the river Irtysh, Trans-Siberian railway - Official figures show

- 10. ‘In the course of all Russian history, from the very beginning of the Russian land right

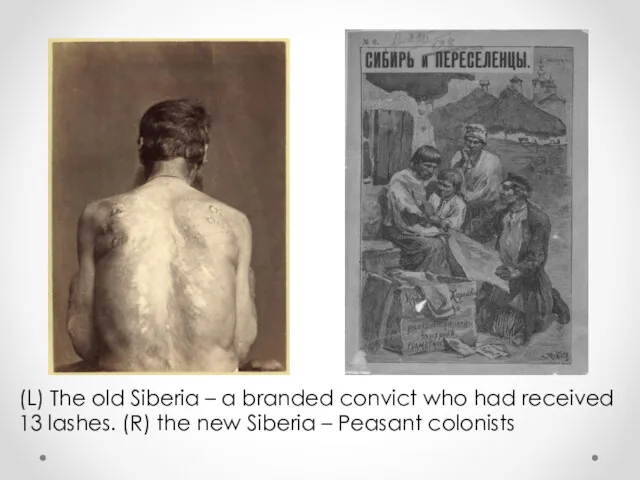

- 11. (L) The old Siberia – a branded convict who had received 13 lashes. (R) the new

- 12. The wooden cathedral in Vernyi (Aziatskaya Rossiya Vol.I facing p.381)

- 13. New divisions in the steppe PART II

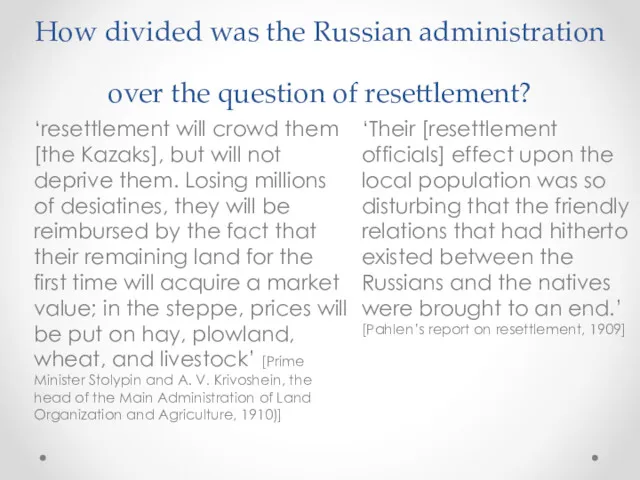

- 14. How divided was the Russian administration over the question of resettlement? ‘Their [resettlement officials] effect upon

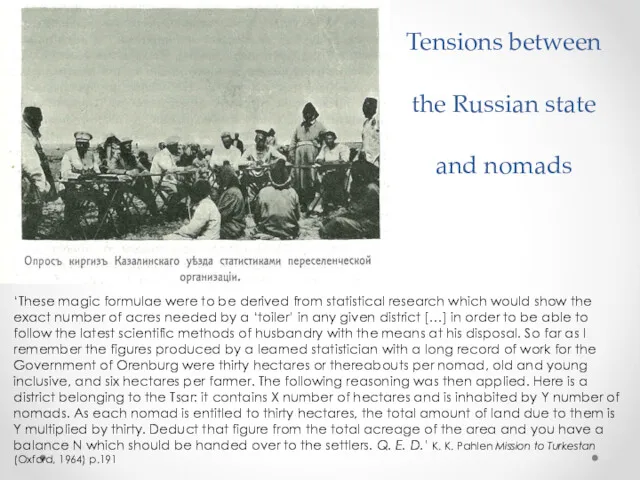

- 15. ‘These magic formulae were to be derived from statistical research which would show the exact number

- 16. Russian administration vs nomads (continued) The so-called izlishki in the steppe are declared state property The

- 17. Settler-nomad divide among Kazakhs

- 18. What socioeconomic divisions emerged in the steppe? ‘Теряя миллионы десятин, они (киргизы) вознаграждаются тем, что остающаяся

- 19. Needs of an industrializing empire vs local environmental and economic concerns

- 20. Ethnic tensions ‘The goal of Russifying the region [tsel’ obruseniya kraya] by means of forcibly disseminating

- 21. Nations as ‘imagined communities’ (Benedict Anderson) Nations are creations because somebody has to tell us that

- 22. Resettlement and the articulation of Kazakh national identity ‘We are convinced that the building of settlements

- 24. Скачать презентацию

![Images of 19th century Irkutsk ‘The resettlement [pereselenie] of state](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/147349/slide-4.jpg)

Афганистан

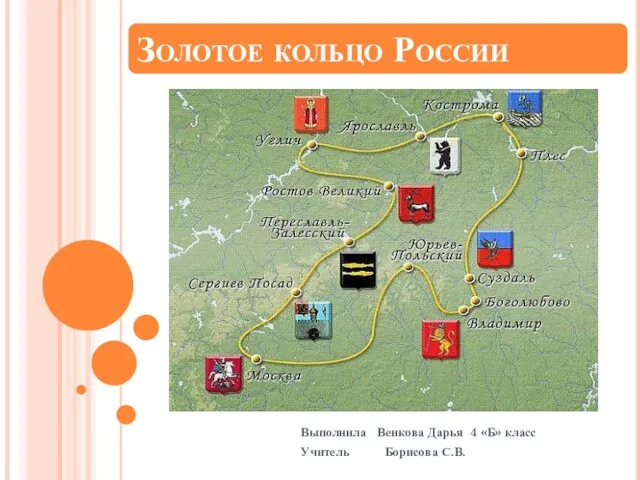

Афганистан Золотое кольцо России

Золотое кольцо России Периодизация современной истории

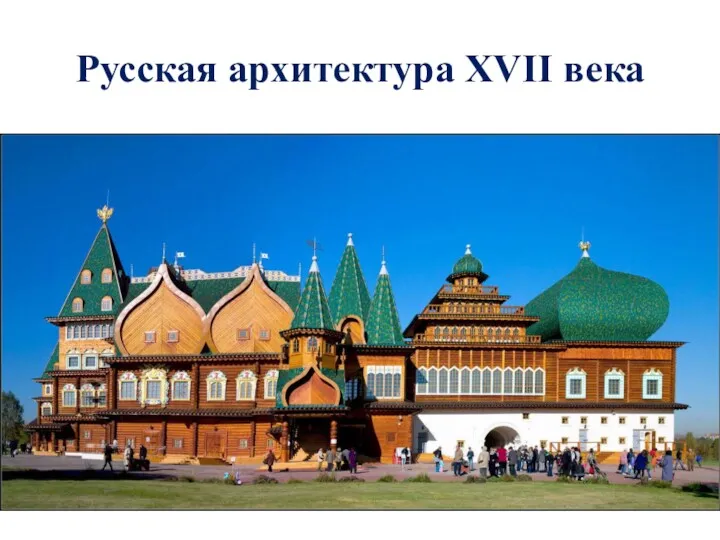

Периодизация современной истории Русская архитектура XVII века

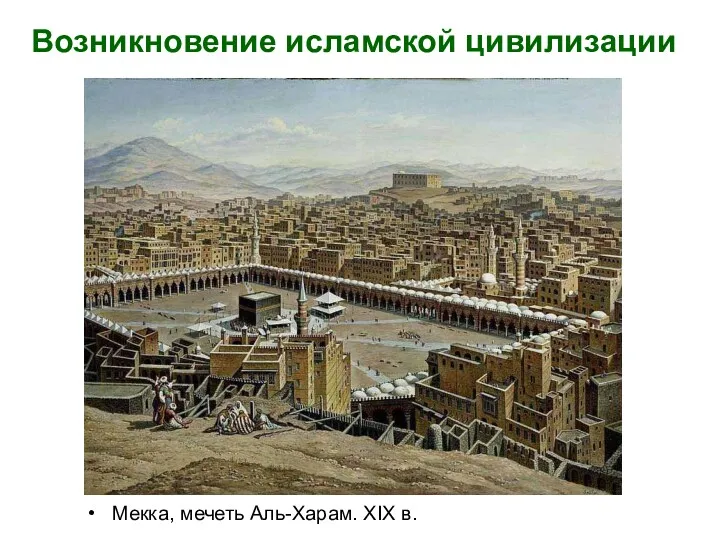

Русская архитектура XVII века Возникновение исламской цивилизации

Возникновение исламской цивилизации Мамыр куні

Мамыр куні Стародавня історія України. Трипільська культура. Кімерійці, скіфи, сармати

Стародавня історія України. Трипільська культура. Кімерійці, скіфи, сармати Открытые уроки. семинары

Открытые уроки. семинары Русские земли на политической карте Европы и мира в начале XV века

Русские земли на политической карте Европы и мира в начале XV века Страны востока и колониальная экспансия европейцев

Страны востока и колониальная экспансия европейцев Появление государства у восточных славян

Появление государства у восточных славян История русской письменности

История русской письменности Перемены в повседневной жизни российских сословий. 8 класс

Перемены в повседневной жизни российских сословий. 8 класс Республиканская акция памяти Поиск солдата

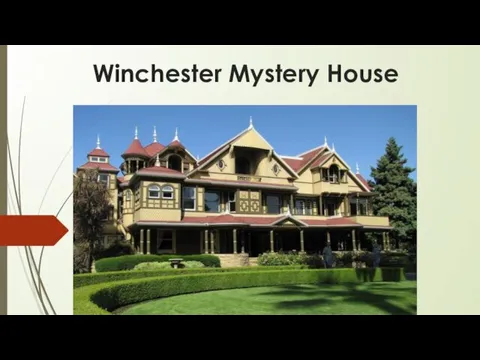

Республиканская акция памяти Поиск солдата Winchester Mystery House

Winchester Mystery House история_6_07.02.22

история_6_07.02.22 Императорское Русское военно-историческое общество (РВИО)

Императорское Русское военно-историческое общество (РВИО) Война 1812 года

Война 1812 года Проект экскурсии “Парадный Петербург”

Проект экскурсии “Парадный Петербург” Государство гуннов

Государство гуннов Губернская Вятка в XVIII - XIX века

Губернская Вятка в XVIII - XIX века Креативность и открытия

Креативность и открытия Международные отношения в XVII в. Тридцатилетняя война (1618 - 1648)

Международные отношения в XVII в. Тридцатилетняя война (1618 - 1648) Империя Великих Моголов

Империя Великих Моголов Классный час Никто не забыт, ничто не забыто. 1 класс

Классный час Никто не забыт, ничто не забыто. 1 класс Возникновение и видоизменение новогодних игрушек

Возникновение и видоизменение новогодних игрушек Россия в первой половине ХIХ века

Россия в первой половине ХIХ века Архитектура Древней Греции

Архитектура Древней Греции