Содержание

- 2. Ethical issues How should we treat the people on whom we conduct research? Are there activities

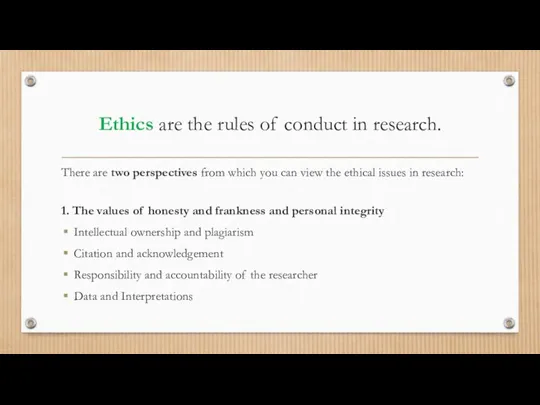

- 3. Ethics are the rules of conduct in research. There are two perspectives from which you can

- 4. 2. Ethical responsibilities to the subjects of research, such as consent, confidentiality and courtesy Anonymity and

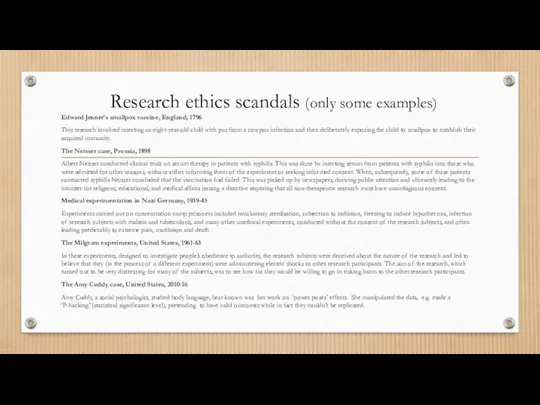

- 5. Research ethics scandals (only some examples) Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine, England, 1796 This research involved injecting

- 6. What is “ethical” research? Based on Diener and Chandall (1978) we can say that behaving ethically

- 7. Asymmetric power relations in research researchers exploit their resources agent provocateur physical harm financial harm social

- 8. How could you harm research participants? Physically By damaging their development or self-esteem By causing stress

- 9. Research participants must know that is what they are and what the research process is But,

- 10. Invasion of privacy Privacy is very much linked to the notion of informed consent The research

- 11. Lies, damned lies and research Deception usually means we represent our research as something other than

- 12. So why should there be a problem? Unfortunately, a lot of writers about ethics in business

- 13. “Research Effects” Hawthorne (Elton Mayo) Placebo John Henry (super-placebo effect) Halo Peacock

- 14. Researcher’s bias researcher is highly biased deep-seated values prejudices – for and against ‘Know thyself’ is

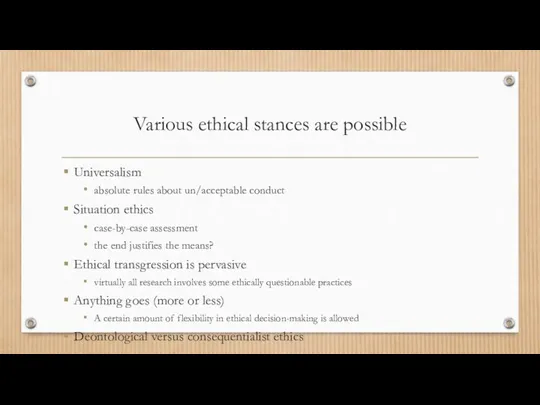

- 15. Various ethical stances are possible Universalism absolute rules about un/acceptable conduct Situation ethics case-by-case assessment the

- 16. Legal considerations The 1998 Data Protection Act* states that personal data must be: obtained only for

- 17. Data Protection Context: IT data storage; state and private sector data banks; personal liberty; IT transfer

- 18. The difficulties of ethical decision-making: a summary The boundary between ethical and unethical practices is not

- 19. New media and ethical considerations Information can be found in many places – blogs, discussion groups,

- 20. Politics in social research Values affect every stage of research process Social research is not conducted

- 21. Politics and Funding Government, organizations and funding bodies have vested interests Which research projects will be

- 22. Gaining access is a political process Gatekeepers mediate access to research settings They can influence how

- 23. Other political issues Research done by a team of researchers can produce conflicting values There may

- 24. Taking sides in social research Becker (1967) values shape social research - inevitable partiality responsibility to

- 25. Doing the right thing….. You can try to do the best you can by making yourself

- 26. Codes of Ethics and legal constraints Ethical codes and guidelines are a means of establishing and

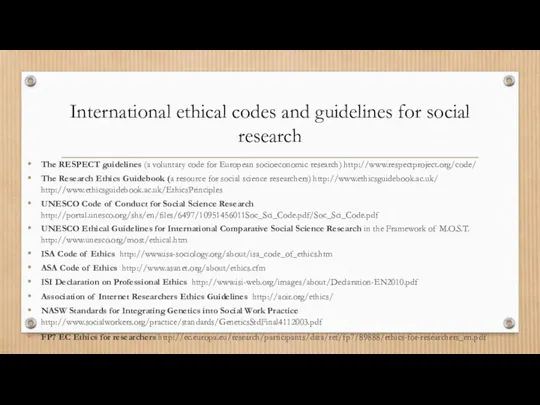

- 27. International ethical codes and guidelines for social research The RESPECT guidelines (a voluntary code for European

- 28. Commonly-used terms Scientific fraud “Fraud” is no longer widely used in this context. It was replaced

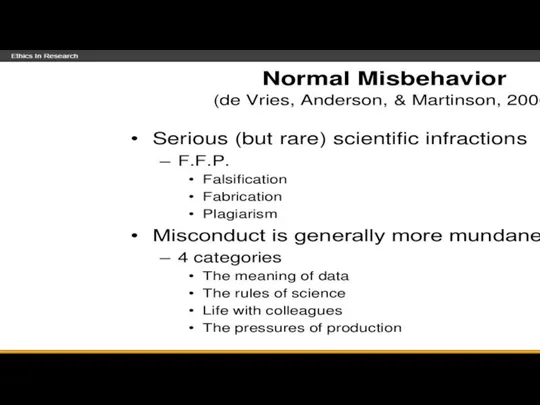

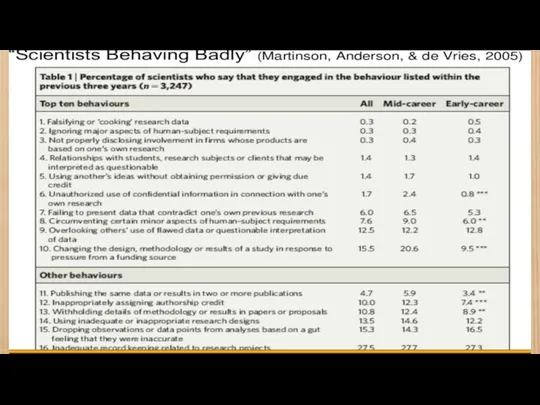

- 29. Questionable research practices Failing to retain significant research data for a reasonable period. Maintaining inadequate research

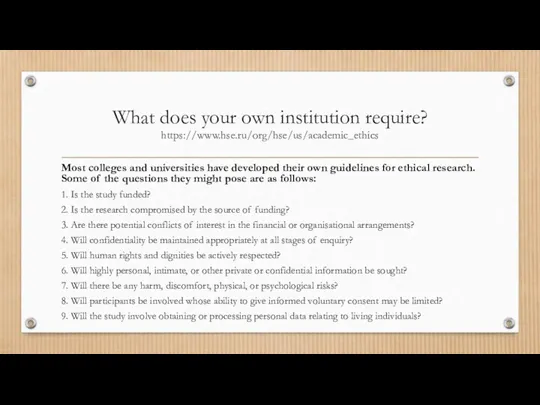

- 33. What does your own institution require? https://www.hse.ru/org/hse/us/academic_ethics Most colleges and universities have developed their own guidelines

- 34. Home reading A. Bryman Social Research Methods 4th edition. Chapter 6 (Dropbox) U. Flick Introducing Research

- 36. Скачать презентацию

Реклама для мужчин и женщин. Различия в подходах

Реклама для мужчин и женщин. Различия в подходах Акция Мама,я тоже хочу немного солнышка

Акция Мама,я тоже хочу немного солнышка Творческое объединение книголюбов Парус

Творческое объединение книголюбов Парус Youth interests in Great Britain

Youth interests in Great Britain Человек и его деятельность. (6 класс)

Человек и его деятельность. (6 класс) Понятие PR: основные субъекты, цели, функции и принципы

Понятие PR: основные субъекты, цели, функции и принципы Національний та етнічний склад населення України

Національний та етнічний склад населення України Семья и быт. 10 класс

Семья и быт. 10 класс Проект Твори добро

Проект Твори добро 1_lektsia

1_lektsia обмен торговля реклама

обмен торговля реклама Социальная структура и социальное пространство современной России

Социальная структура и социальное пространство современной России Выявление уровня осведомлённости людей об инклюзивном туризме

Выявление уровня осведомлённости людей об инклюзивном туризме Проект Дети войны - детям мира

Проект Дети войны - детям мира Гендерные различия феномена лидерства

Гендерные различия феномена лидерства Лагерь досуга и отдыха: Летний экспресс Парма-транзит-Пермь. Гражданско-патриотическая направленность

Лагерь досуга и отдыха: Летний экспресс Парма-транзит-Пермь. Гражданско-патриотическая направленность Образование и самообразование

Образование и самообразование Отчетно-выборная конференция Первичной Профсоюзной Организации

Отчетно-выборная конференция Первичной Профсоюзной Организации Подросток и семья

Подросток и семья Правовой Совет Института Непрерывного Образования имени Н.С. Киселёвой

Правовой Совет Института Непрерывного Образования имени Н.С. Киселёвой Урок-игра Молодежь в современном мире

Урок-игра Молодежь в современном мире Гражданский брак. За или Против

Гражданский брак. За или Против Результаты социологического опроса жителей Васильевского острова о Новосмоленской набережной

Результаты социологического опроса жителей Васильевского острова о Новосмоленской набережной Духовная сфера общества

Духовная сфера общества Структурализм, постструктурализм (постмодернизм) как парадигмы юридических исследований

Структурализм, постструктурализм (постмодернизм) как парадигмы юридических исследований Віддай частинку себе

Віддай частинку себе Презентация. Обществознание 10-11 класс. Девиантное поведение.

Презентация. Обществознание 10-11 класс. Девиантное поведение. Общество как социальная система

Общество как социальная система