Содержание

- 2. “NO TOPIC IS MORE INTERESTING TO PEOPLE THAN PEOPLE. FOR MOST PEOPLE, MOREOVER, THE MOST INTERESTING

- 3. What is the “self”? In psychology: collection of cognitively-held beliefs that a person possesses about themselves.

- 4. What is the “self”? Most recently, “self” has been further complexified and increasingly seen as: Dynamic

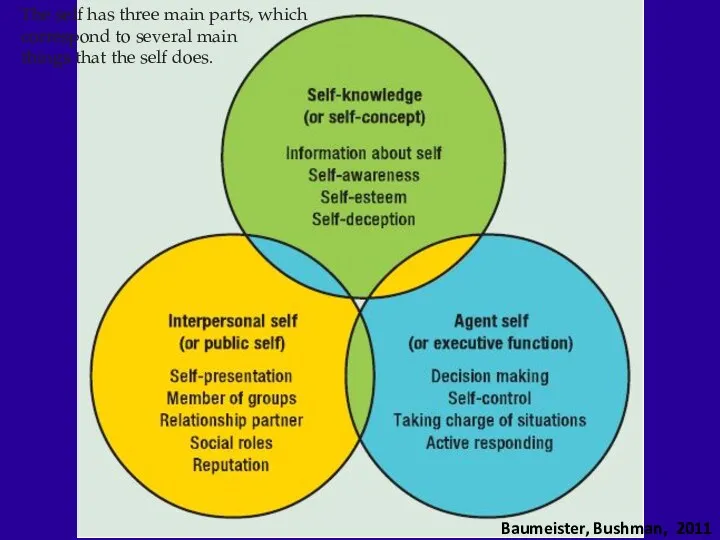

- 5. Baumeister, Bushman, 2011 The self has three main parts, which correspond to several main things that

- 6. Self-concept Human beings have self-awareness, and this awareness enables them to develop elaborate sets of beliefs

- 7. Interpersonal self A second part of the self that helps the person connect socially to other

- 8. Agent Self The third important part of the self, the agent self, or executive function, is

- 9. Self-concept Self-awareness Self-esteem Self-deception Self-efficacy

- 10. Self-awareness Attention directed to the self Usually involves evaluative comparison. In general, people spend little time

- 11. Self-awareness Early in the 1970s social psychologists began studying the difference between being and not being

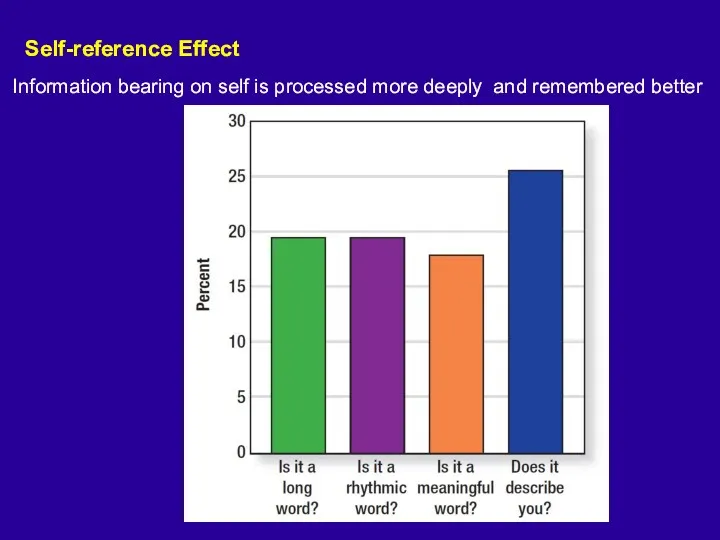

- 12. Self-reference Effect Information bearing on self is processed more deeply and remembered better

- 13. Social Comparison Theory Festinger suggested that people compare themselves to others because, for many domains and

- 16. Social Comparison Theory Festinger suggested that people compare themselves to others because, for many domains and

- 19. self-affirmation theory People seek new favourable knowledge about themselves as well as ways to revise pre-existing

- 20. Self-Evaluation Maintenance Model In order to maintain a positive view of the self, we distance ourselves

- 21. Self-deception strategies Self Serving Bias (mentioned in the previous lecture) More skeptical of bad feedback Comparisons

- 22. Self-awareness Private self-awareness refers to attending to your inner states, including emotions, thoughts, desires, and traits.

- 23. Self-Monitoring Self-monitoring is the degree to which you are aware of how your actions and behaviors

- 24. Self-Monitoring What are the dangers of being a: High Self-Monitor (adjusts behavior to situation; monitors situation)

- 25. Is high or low-self-monitoring related to job success? Research (meta-analysis) has shown that high self-monitoring is

- 26. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps one to overcome bad feelings If they fail, they

- 27. Self-esteem Self-esteem reflects a person's overall subjective emotional evaluation of his or her own worth. It

- 28. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps one to overcome bad feelings If they fail, they

- 29. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps one to overcome bad feelings If they fail, they

- 30. Self-esteem Self-esteem serves as a sociometer for one’s standing in a group. Sociometer theory This theoretical

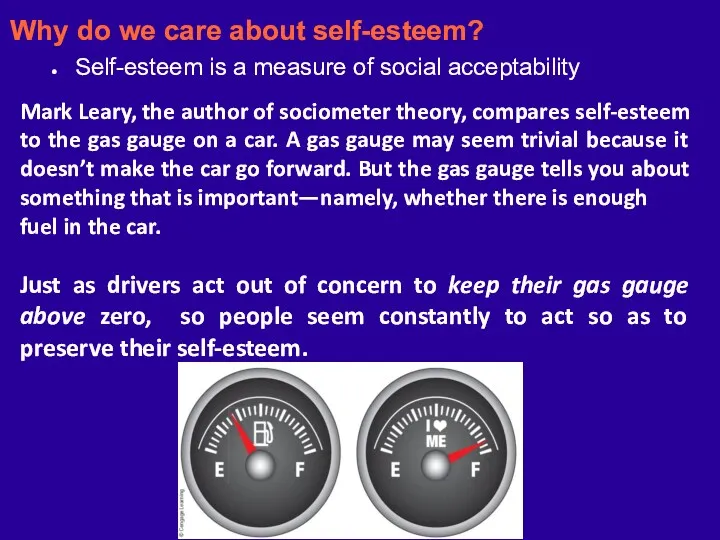

- 31. Why do we care about self-esteem? Self-esteem is a measure of social acceptability A sociometer (made

- 32. Why do we care about self-esteem? Self-esteem is a measure of social acceptability Mark Leary, the

- 33. A common view is that self-esteem is based mainly on feeling competent rather than on social

- 34. Negative aspects of highest self-esteem Narcissism Subset of high self-esteem Tend to be more aggressive and

- 35. Self-efficacy Belief in one’s capacity to succeed at a given task. e.g. Public Speaking Self-Efficacy Bandura

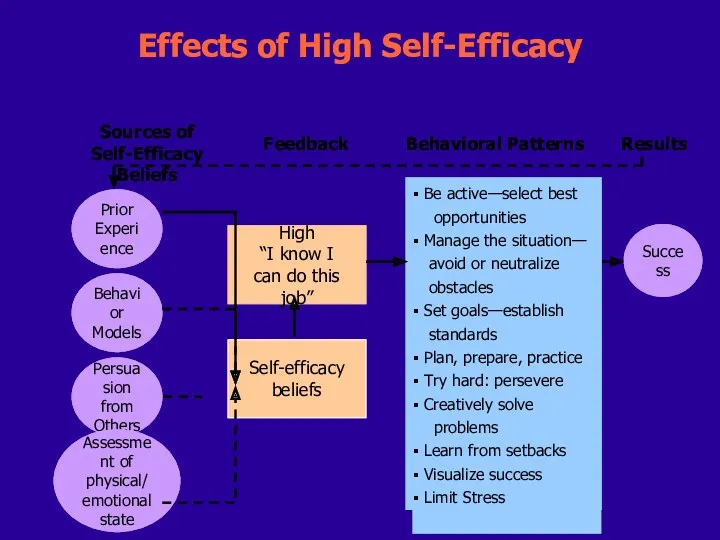

- 36. Effects of High Self-Efficacy Prior Experience Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs Feedback Behavioral Patterns Results High “I

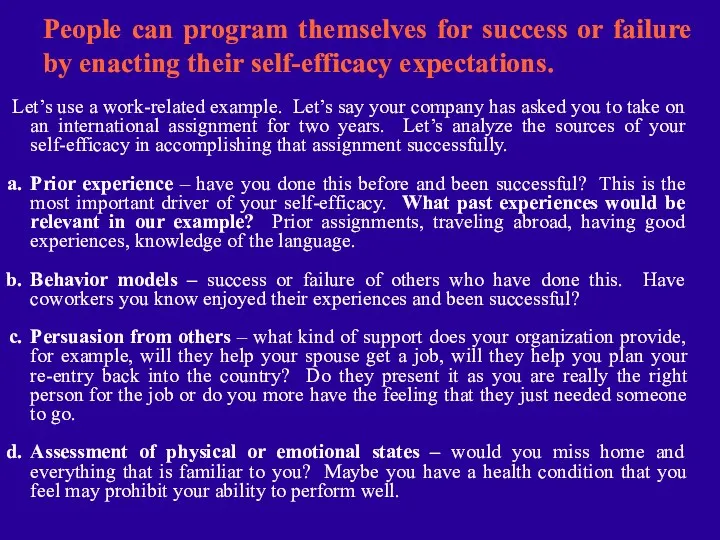

- 37. People can program themselves for success or failure by enacting their self-efficacy expectations. Let’s use a

- 38. Effects of High Self-Efficacy Prior Experience Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs Feedback Behavioral Patterns Results High “I

- 39. Effects of Low Self-Efficacy Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs Feedback Behavioral Patterns Results Self-efficacy beliefs Low “I

- 41. The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)

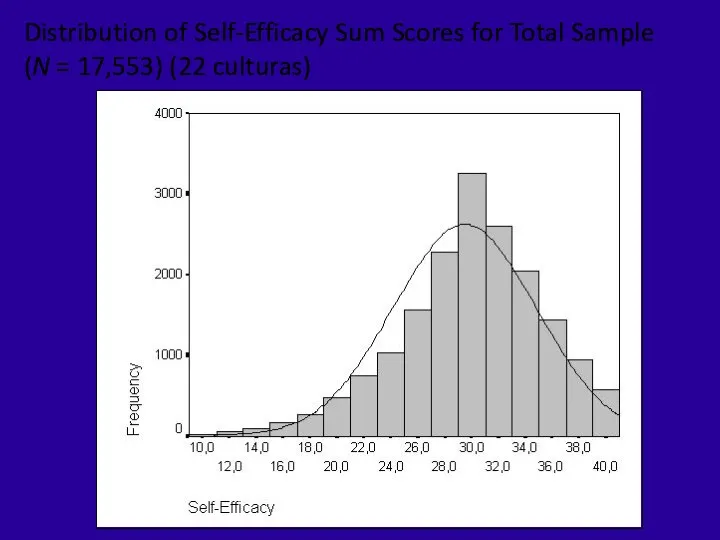

- 42. Distribution of Self-Efficacy Sum Scores for Total Sample (N = 17,553) (22 culturas)

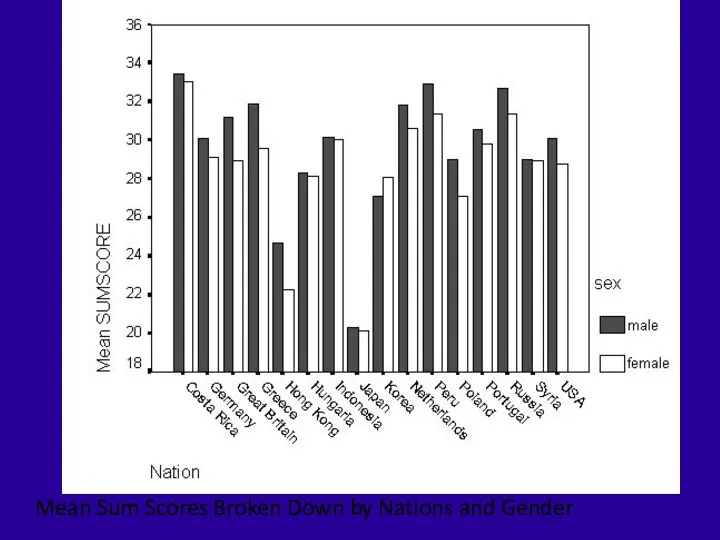

- 43. Mean Sum Scores Broken Down by Nations and Gender

- 44. Interpersonal self self – presentation Behaviors that convey an image to others Public esteem More important

- 45. Functions of self-presentation Social acceptance Increase chance of acceptance and maintain place within the group Claiming

- 46. Interpersonal Self The idea that cultural styles of selfhood differ along the dimension of independence was

- 47. self-construal Markus and Kitayama (1991) published their classic article on culture and the self, proposing that

- 48. self-construal They argued that Western cultures are unusual in promoting an independent view of the self

- 49. Interdependent of Self-Concept In individualistic cultures it is expected that people will develop a self-concept separate

- 50. self-construal They proposed that people with independent self-construals would strive for self-expression, uniqueness, and self-actualization, basing

- 52. self-construal Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) proposals had a dramatic impact on social, personality and developmental psychology,

- 53. self-construal Their work may have added scientific legitimacy to a common tendency to understand culture in

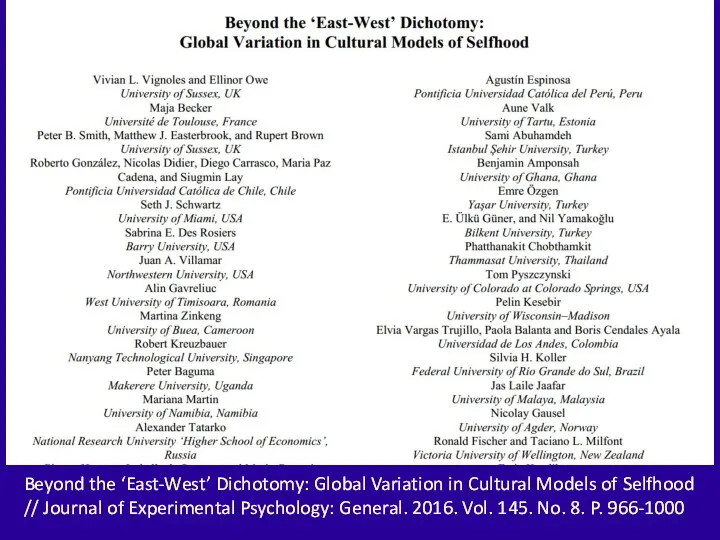

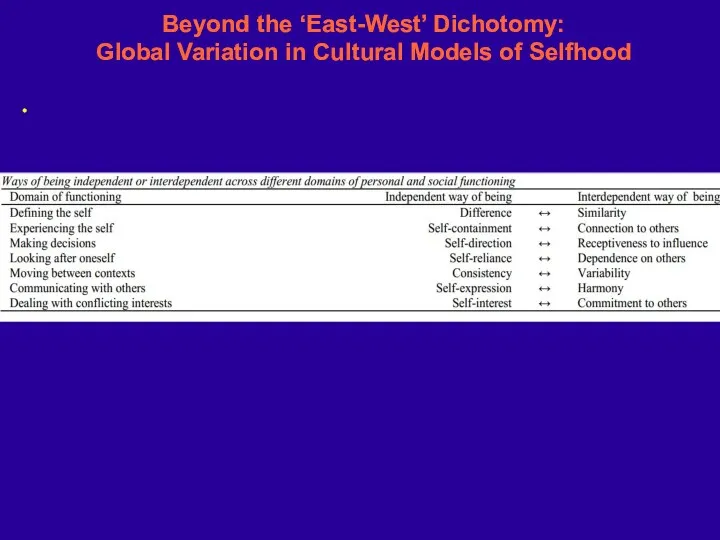

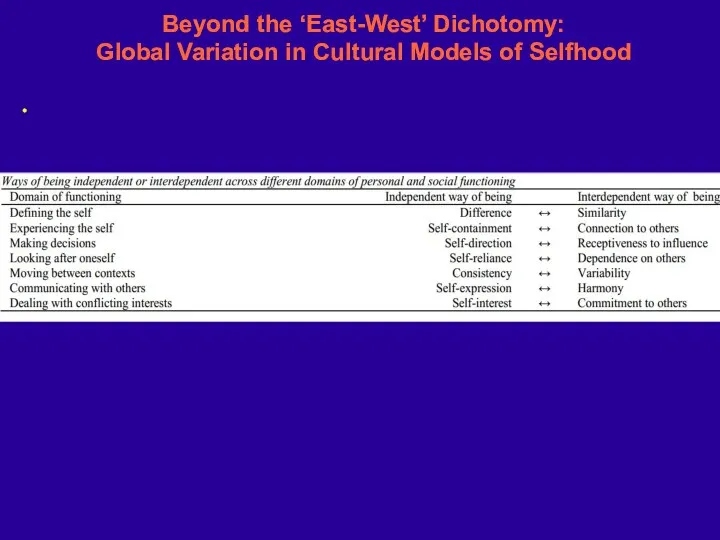

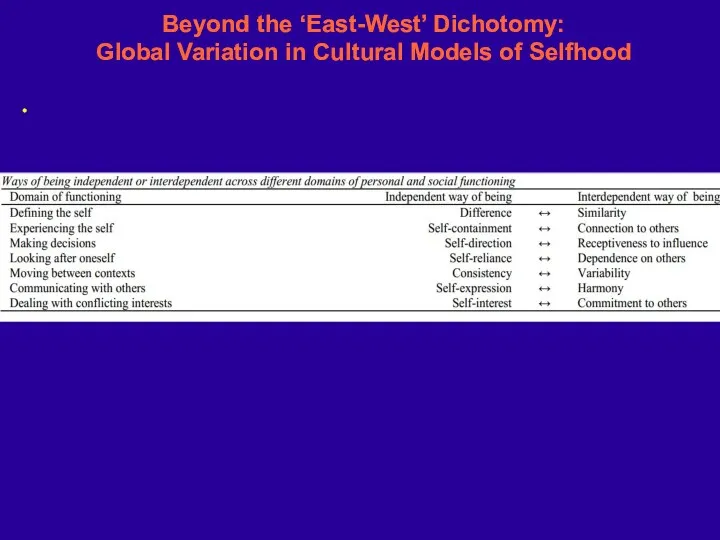

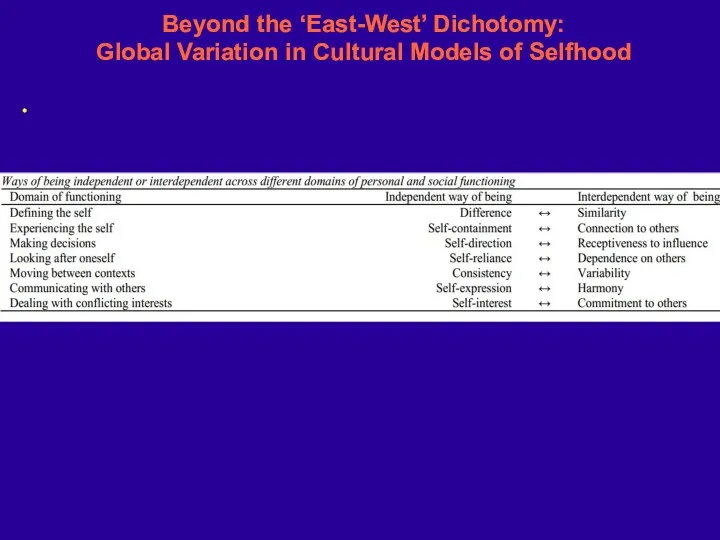

- 54. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood // Journal of Experimental Psychology:

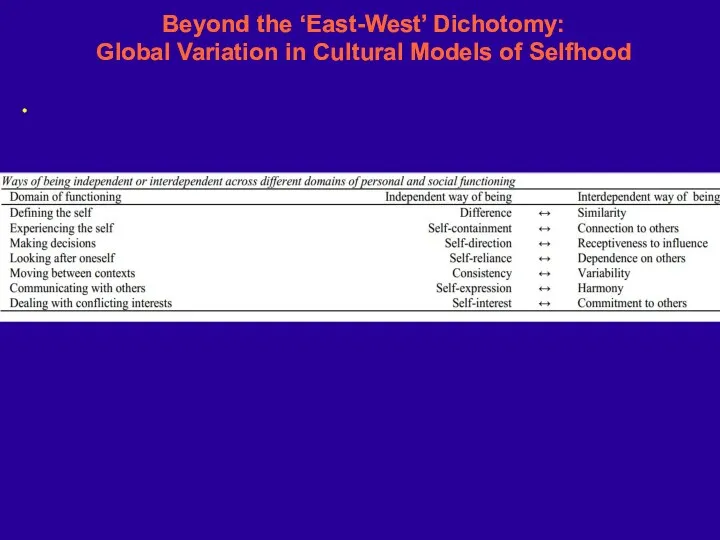

- 55. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood Markus and Kitayama’s original characterization

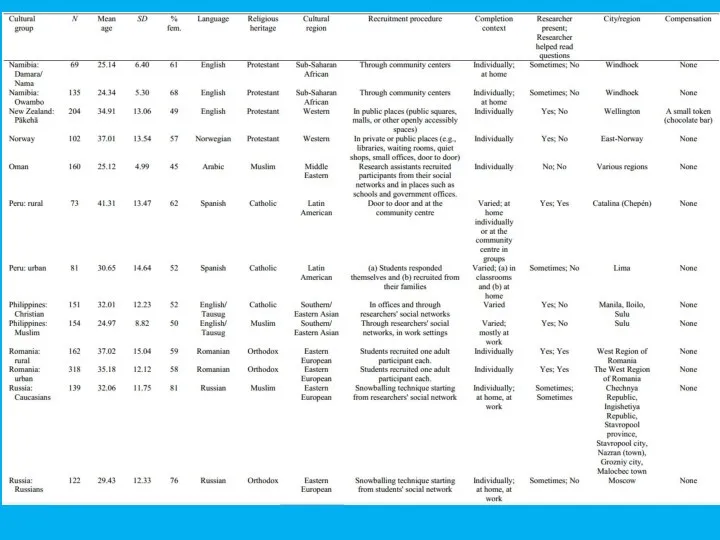

- 56. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood We sampled participants from 16

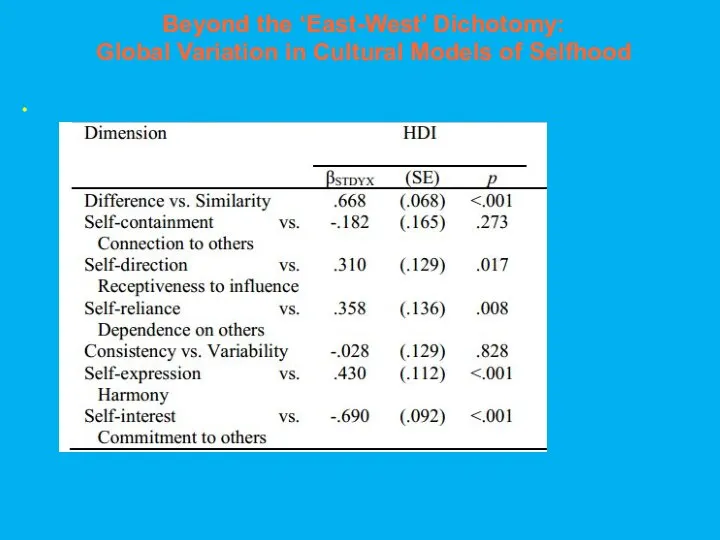

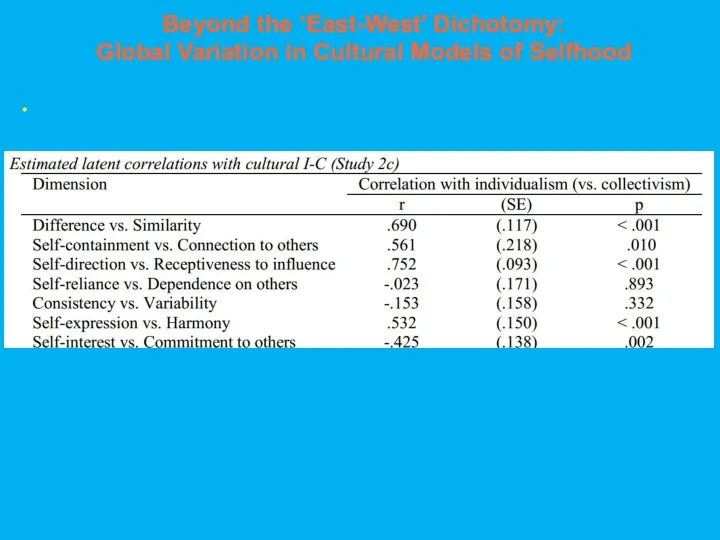

- 57. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood We tested our seven-dimensional model

- 58. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 59. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

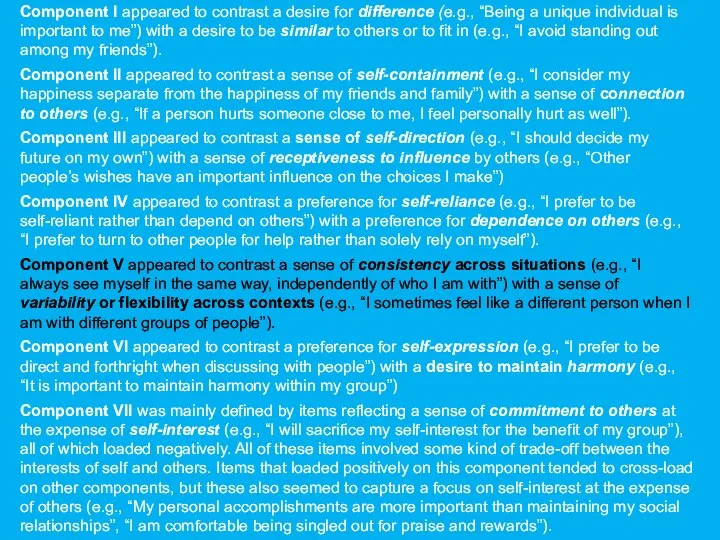

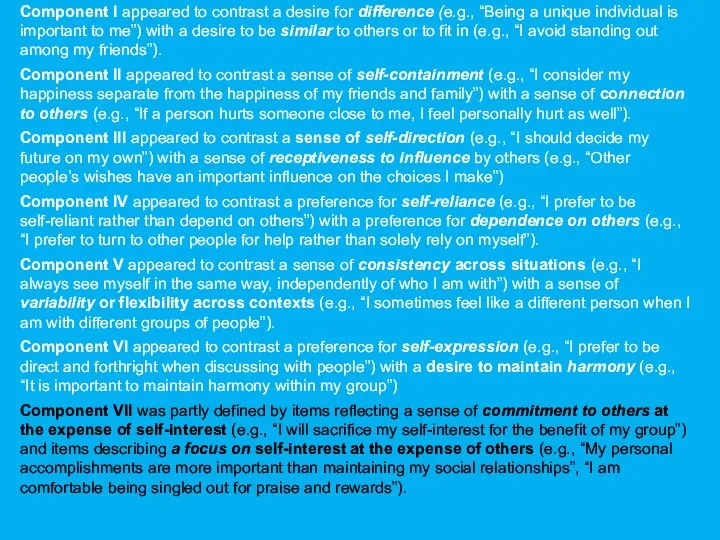

- 60. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 61. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 62. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 63. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 64. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 65. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 66. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 67. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 68. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 69. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 70. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 71. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 72. Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important

- 73. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 74. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 75. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood In closing, we have argued

- 76. Self-Interest

- 77. Self-interest THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

- 78. The Forer effect (also called the Barnum effect after P. T. Barnum's observation that "we've got

- 79. This effect can provide a partial explanation for the widespread acceptance of some beliefs and practices,

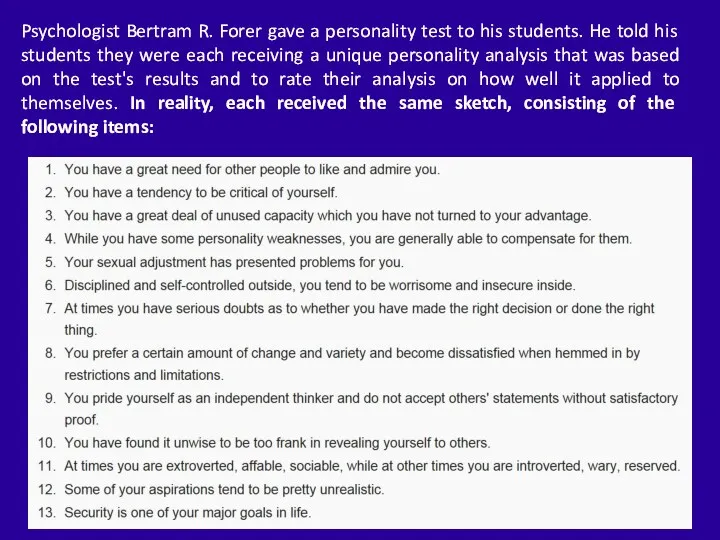

- 80. Psychologist Bertram R. Forer gave a personality test to his students. He told his students they

- 81. On average, the students rated its accuracy as 4.26 on a scale of 0 (very poor)

- 82. THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect) Subjects give higher accuracy ratings if... ○ The subject believes analysis

- 85. Скачать презентацию

Презентация к уроку Роль СМИ в жизни общества

Презентация к уроку Роль СМИ в жизни общества Галактическое движение. Работа в радость

Галактическое движение. Работа в радость Гражданское общество

Гражданское общество Команда “Семейка SHI”. Семейные традиции

Команда “Семейка SHI”. Семейные традиции Взаимоотношения в семье

Взаимоотношения в семье Социальный проект Социальная гостиница

Социальный проект Социальная гостиница Социальная политика в Германии

Социальная политика в Германии Профсоюзный отчет Кубанскостепного сельского поселения

Профсоюзный отчет Кубанскостепного сельского поселения Проектирование программ социального обслуживания семей имеющего ребенка-инвалида

Проектирование программ социального обслуживания семей имеющего ребенка-инвалида Volunteers wanted

Volunteers wanted Роль СМИ в политической жизни.

Роль СМИ в политической жизни. ММО Волонтёры

ММО Волонтёры Волгоградский областной социально-реабилитационный центр для несовершеннолетних, проект Ключи от дома

Волгоградский областной социально-реабилитационный центр для несовершеннолетних, проект Ключи от дома Социология молодежи

Социология молодежи Международные организации

Международные организации Человек в системе социальных связей. Социальное поведение

Человек в системе социальных связей. Социальное поведение План работы студенческого отряда с мая 2019 года по май 2020 года

План работы студенческого отряда с мая 2019 года по май 2020 года Конфликты в обществе

Конфликты в обществе Деятельность волонтёрского отряда Данко. Нытвенский многопрофильный техникум

Деятельность волонтёрского отряда Данко. Нытвенский многопрофильный техникум Презентация Секты

Презентация Секты Молодежь как социальная группа

Молодежь как социальная группа Семья как ведущий фактор социализации личности

Семья как ведущий фактор социализации личности Метод фокус-группа

Метод фокус-группа Рабочая неделя Главы Тракторозаводского района

Рабочая неделя Главы Тракторозаводского района Социальная акция. От идеи к реализации

Социальная акция. От идеи к реализации Изучение состояния доступности объектов социальной инфраструктуры на уровне п. Динамо. 2 класс

Изучение состояния доступности объектов социальной инфраструктуры на уровне п. Динамо. 2 класс Презентация Малая группа

Презентация Малая группа Презентация Уголовная ответственность несовершеннолетних

Презентация Уголовная ответственность несовершеннолетних