Содержание

- 2. Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English, began to become widespread, a process aided by the

- 3. THE AGE OF CHANGES

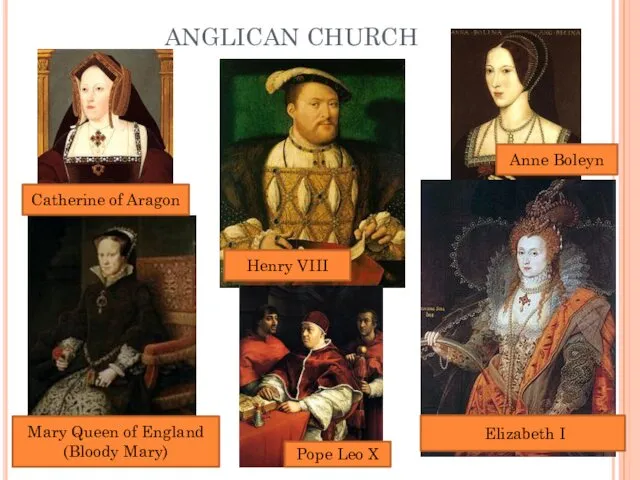

- 4. ANGLICAN CHURCH Henry VIII Catherine of Aragon Mary Queen of England (Bloody Mary) Pope Leo X

- 5. Elizabethian Age Since 1558 Defeated Spanish Armada Britain became a super economic power Colonies, Age of

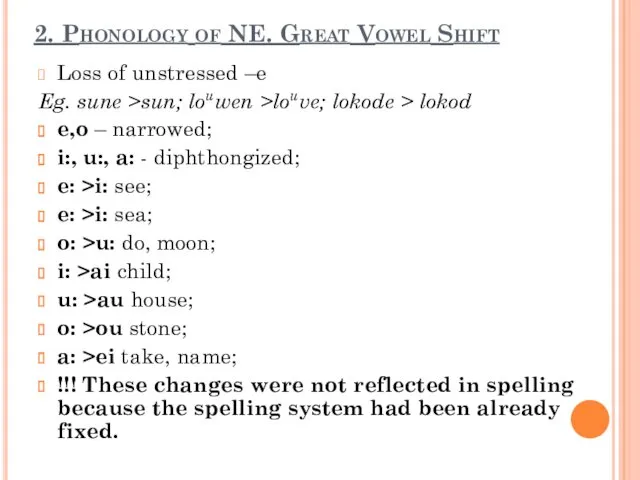

- 6. 2. Phonology of NE. Great Vowel Shift Loss of unstressed –e Eg. sune >sun; louwen >louve;

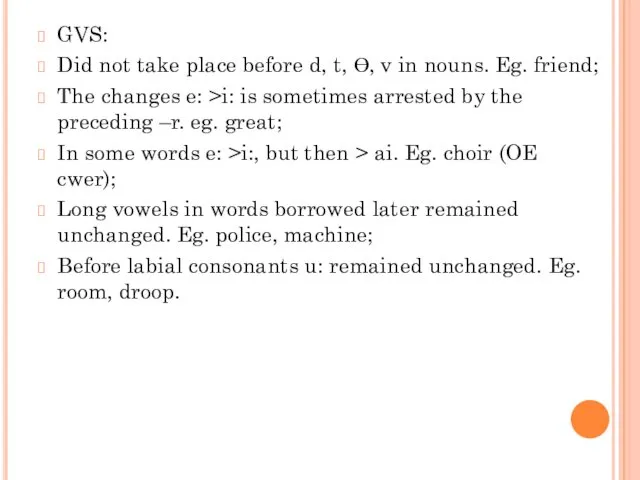

- 7. GVS: Did not take place before d, t, ϴ, v in nouns. Eg. friend; The changes

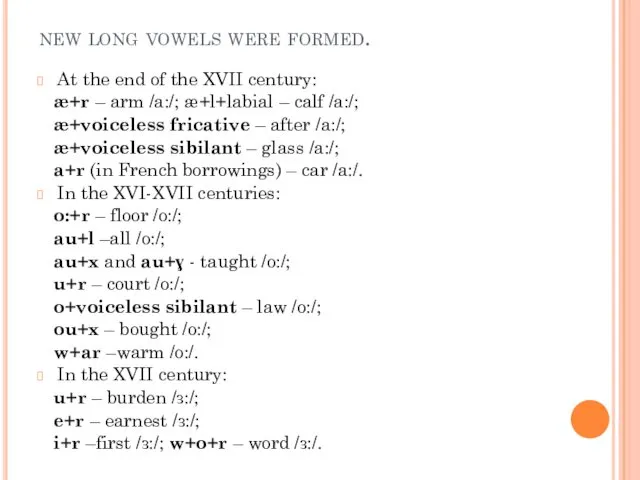

- 8. new long vowels were formed. At the end of the XVII century: æ+r – arm /a:/;

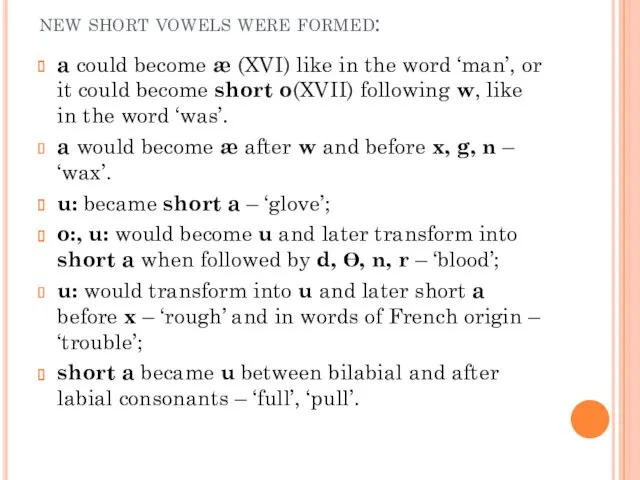

- 9. new short vowels were formed: a could become æ (XVI) like in the word ‘man’, or

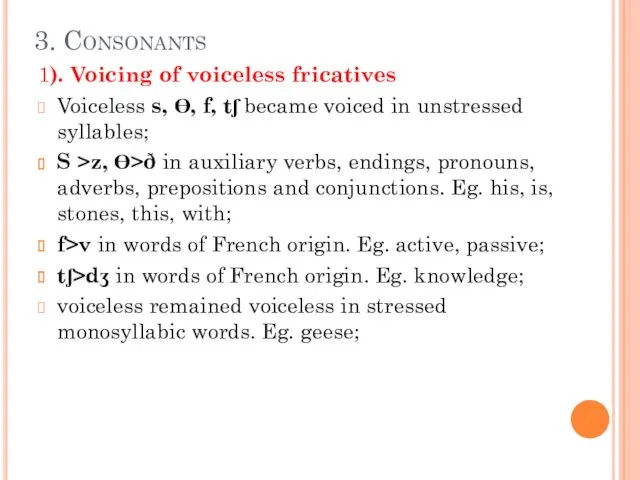

- 10. 3. Consonants 1). Voicing of voiceless fricatives Voiceless s, ϴ, f, tʃ became voiced in unstressed

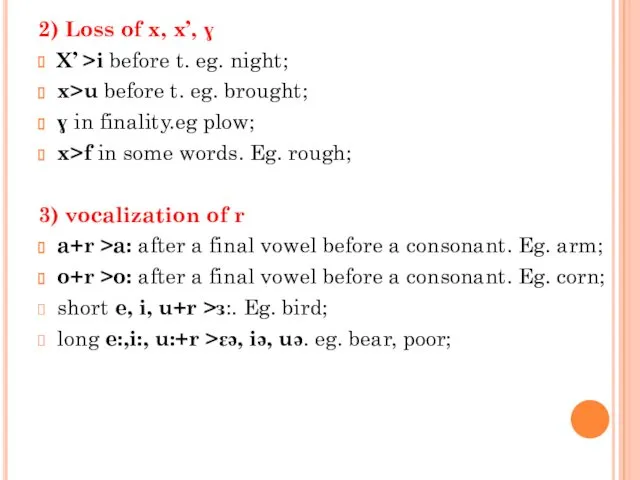

- 11. 2) Loss of x, x’, ɣ X’ >i before t. eg. night; x>u before t. eg.

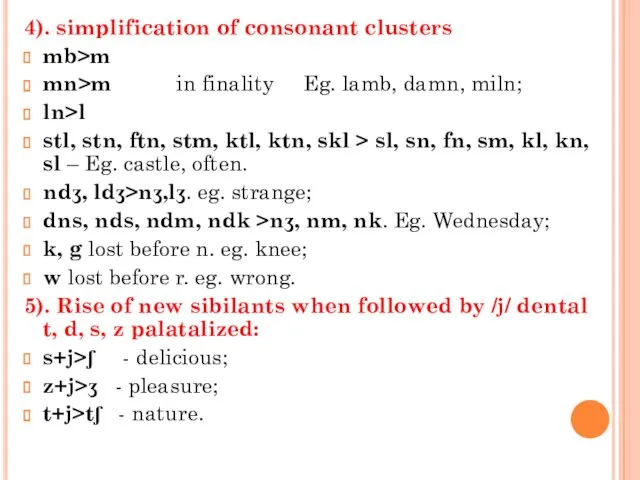

- 12. 4). simplification of consonant clusters mb>m mn>m in finality Eg. lamb, damn, miln; ln>l stl, stn,

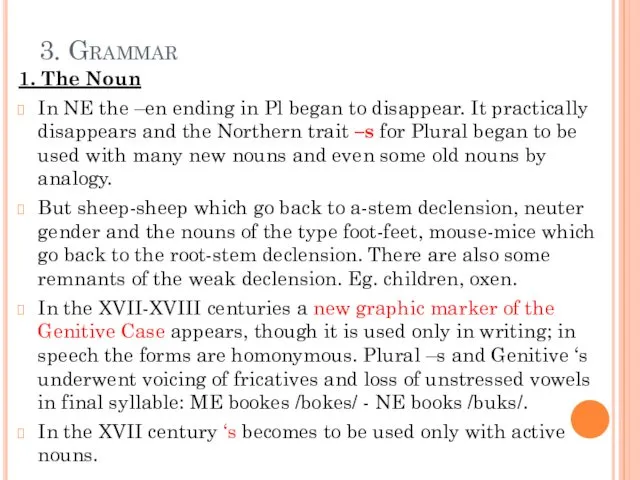

- 13. 3. Grammar 1. The Noun In NE the –en ending in Pl began to disappear. It

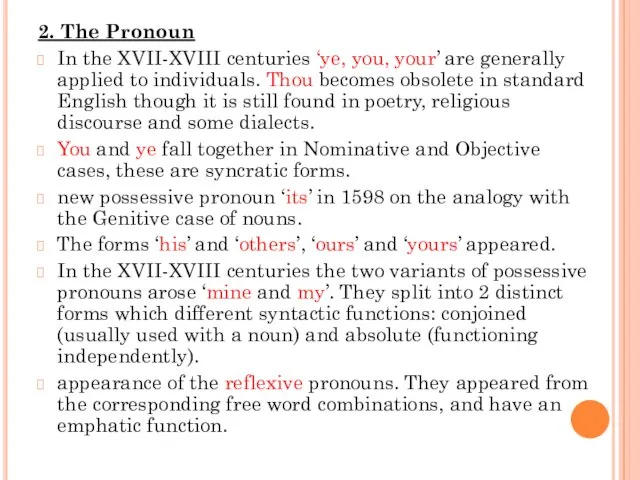

- 14. 2. The Pronoun In the XVII-XVIII centuries ‘ye, you, your’ are generally applied to individuals. Thou

- 15. 3. The Adjective the adjective becomes an entirely uninflected part of speech and looses all the

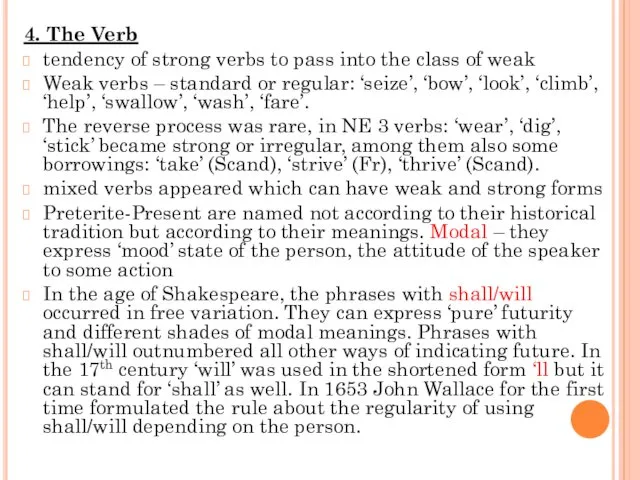

- 16. 4. The Verb tendency of strong verbs to pass into the class of weak Weak verbs

- 18. Скачать презентацию

Australian music

Australian music Давайте вспомним, что мы узнали в прошлом году. Повторение

Давайте вспомним, что мы узнали в прошлом году. Повторение Clownfish

Clownfish Does Russia have the same ecological problems as the rest of the world

Does Russia have the same ecological problems as the rest of the world Minions race simple teacher switcher

Minions race simple teacher switcher Prepositions of time in, on, at

Prepositions of time in, on, at Halloween

Halloween Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers English Language Day

English Language Day Различие глаголов Do и Make в английском языке

Различие глаголов Do и Make в английском языке School rules

School rules Организация обучения чтению на уроке английского языка по методике Jolly Phonics

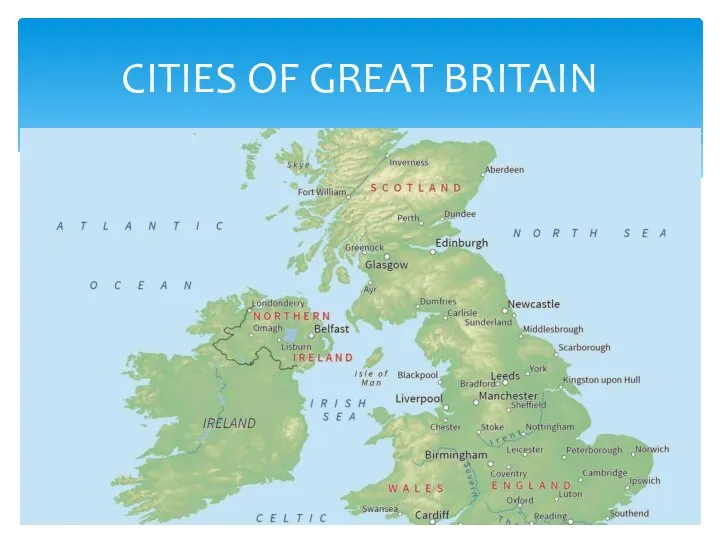

Организация обучения чтению на уроке английского языка по методике Jolly Phonics Cities Of Great Britain

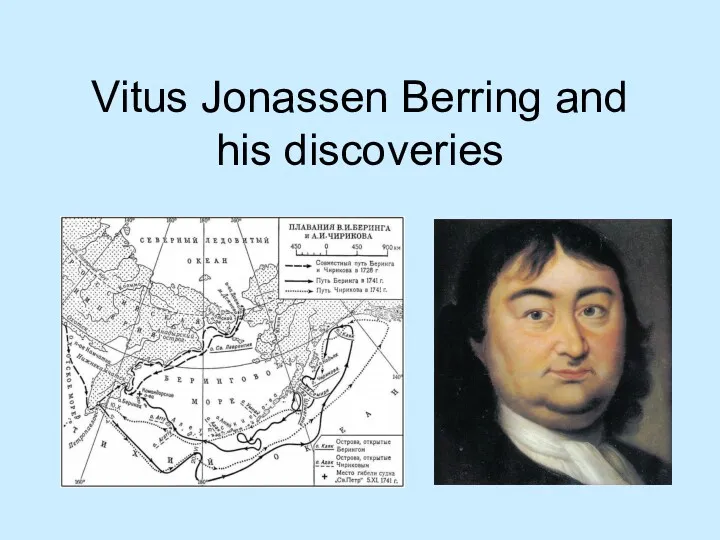

Cities Of Great Britain Vitus Jonassen Berring and his discoveries

Vitus Jonassen Berring and his discoveries My mobile phone Samsung Galaxy J1 mini

My mobile phone Samsung Galaxy J1 mini My house

My house Irregular Verbs. Same forms

Irregular Verbs. Same forms Gerunds and infinitives

Gerunds and infinitives Perfect Tenses

Perfect Tenses The capital of Ukraine is Kyiv

The capital of Ukraine is Kyiv Global environmental problems and solutions

Global environmental problems and solutions Why do we study English

Why do we study English English grammar

English grammar What is a cell

What is a cell Why i love me school

Why i love me school Opposites. Game

Opposites. Game Английский марафон

Английский марафон ABC book

ABC book