Содержание

- 2. This module will enable you to understand Which animals we are concerned about and why Sentience

- 3. Background For thousands of years, humans around the world have been concerned that animals are suffering.

- 4. Definitions (1) Sentience “A sentient being is one that has some ability: to evaluate the actions

- 5. Sentience continued Sentience is the capacity to experience suffering and pleasure It implies a level of

- 6. Definitions (2) Suffering “One or more bad feelings continuing for more than a short period.” (Broom

- 7. Anthropomorphism Anthropomorphism generally criticised Using a “human-based” assessment may be a useful first step (Webster, 2011)

- 8. Which sentient animals are vets concerned about? Species that we keep: domesticated and captive wild species

- 9. Welfare and death Welfare Welfare concerns the quality of an animal’s life, not how long the

- 10. Summary so far Although highly criticised, anthropomorphism can be helpful, but is not enough on its

- 11. Definitions of animal welfare There is still much disagreement about animal welfare because of different ethical

- 12. What is animal welfare? Complex concept with three areas of concern (Fraser et al., 1997) Is

- 13. Three approaches when considering animal welfare After Appleby, M. C. (1999) and Fraser et al. (1997)

- 14. Definitions of animal welfare: ‘physical’ “The welfare of an animal is its state as regards its

- 15. Definitions: ‘mental’ “... Neither health nor lack of stress nor fitness is necessary and/or sufficient to

- 16. Natural behaviour “In principle, we disapprove of a degree of confinement of an animal which necessarily

- 17. ‘Feelings’, ‘naturalness’ and needs (Widowski, 2010) Specific behaviours that animals developed in order to obtain an

- 18. Combined statements (1) World Organisation for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties; OIE). Terrestrial Animal Health

- 19. Combined statements (2) The Five Freedoms (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 1992) are often used as a

- 20. Summary so far Definitions Suffering – “one or more bad feelings continuing for more than a

- 21. History India Ahimsa: do not cause injury to any living being Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism (Taylor, 1999)

- 22. History China: Confucianism Because of one-ness with all beings, the suffering of animals is a source

- 23. Ancient Greece (Fraser, 2008a) The same range of arguments as we have today. For example: Pythagoras

- 24. Britain in 18th and 19th centuries (Fraser, 2008a) Treatment of animals in Britain had been very

- 25. Modern agriculture In Europe and North America, farming became more industrialised in 1950s and 1960s focus

- 26. History Growing public and scientific concern in 1960s onwards, regarding farmed animals UK: Ruth Harrison (1964)

- 27. Animal welfare science Mandated to answer specific questions of public concern (Fraser, 2008a) Brambell Committee (1965)

- 28. Scientific

- 29. International importance (1) World Organisation for Animal Heath (OIE, 2011b) 178 member countries and territories “Takes

- 30. International importance (2) One Health Initiative (2011) “Worldwide strategy for expanding interdisciplinary collaborations and communications in

- 31. Vets and animal welfare science Infectious disease prevention and eradication ~60 vaccines (Mellor et al., 2009)

- 32. In the 21st century (1) Animal welfare science now a recognised discipline in vet schools around

- 33. In the 21st century (2) Many people feel we have an obligation to animals (Broom, 2010)

- 34. Final points Animal welfare is a complex concept Understanding it requires science (how different environments affect

- 35. References Appleby, M.C., (1999) What Should We Do About Animal Welfare? Oxford, Blackwell. Barnard, C.J. &

- 36. References Fraser, D., Weary, D. M., Pajor, E. A., & Milligan, B. N. (1997). A scientific

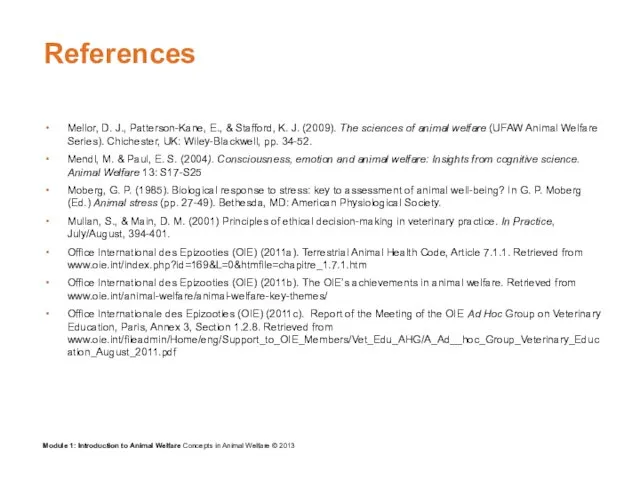

- 37. References Mellor, D. J., Patterson-Kane, E., & Stafford, K. J. (2009). The sciences of animal welfare

- 39. Скачать презентацию

Природные уникумы Урала. Экологические проблемы

Природные уникумы Урала. Экологические проблемы Биологические ресурсы, их рациональное использование

Биологические ресурсы, их рациональное использование Экология Республики Адыгеи

Экология Республики Адыгеи Адамзат үшін ядролық сынақтың салдары. Жер бетінде түрлі мутацияға ұшыраған адамдар мен жануарлардың дүниеге келуі

Адамзат үшін ядролық сынақтың салдары. Жер бетінде түрлі мутацияға ұшыраған адамдар мен жануарлардың дүниеге келуі Концепция экологической безопасности

Концепция экологической безопасности Природные ресурсы и их классификация

Природные ресурсы и их классификация Рациональное питание

Рациональное питание Конспект + презентация занятия по экологии Птицы широколиственного леса для 6 класса коррекционной школы VIII вида.

Конспект + презентация занятия по экологии Птицы широколиственного леса для 6 класса коррекционной школы VIII вида. Наш дом - Земля

Наш дом - Земля Загрязнение и охрана окружающей среды. Антропогенное загрязнение окружающей среды

Загрязнение и охрана окружающей среды. Антропогенное загрязнение окружающей среды Концепция Зеленый дом

Концепция Зеленый дом Учение о биосфере В.И. Вернадского

Учение о биосфере В.И. Вернадского Экологиялық факторлар

Экологиялық факторлар Global water economy complex

Global water economy complex Чистый Берег

Чистый Берег Загрязнение воды. Методы очистки воды

Загрязнение воды. Методы очистки воды Использование технологии проблемного обучения для развития познавательной активности обучающихся.

Использование технологии проблемного обучения для развития познавательной активности обучающихся. Село без свалок. Влияние бытовых отходов на окружающую природу и жизнь человека

Село без свалок. Влияние бытовых отходов на окружающую природу и жизнь человека Введение в экологию. Экология с точки зрения человека. Антропоцентрический и биоцентрический подходы

Введение в экологию. Экология с точки зрения человека. Антропоцентрический и биоцентрический подходы Расчет кратности разбавления сточных вод

Расчет кратности разбавления сточных вод Заповедные острова Республики Башкортостан

Заповедные острова Республики Башкортостан Растения, занесённые в Красную Книгу

Растения, занесённые в Красную Книгу Экологические причины изменения структуры сельскохозяйственных земель Республики Башкортостан

Экологические причины изменения структуры сельскохозяйственных земель Республики Башкортостан How to save the Earth

How to save the Earth Подбор ассортимента растений для озеленения интерьера в зависимости от их экологических особенностей

Подбор ассортимента растений для озеленения интерьера в зависимости от их экологических особенностей Учение о биосфере

Учение о биосфере Экологические системы

Экологические системы От экологических кризисов и катастров к устойчивому развитию

От экологических кризисов и катастров к устойчивому развитию