Содержание

- 2. Overview What is the Mind? What does it mean to have a mind? How are the

- 3. What is the Mind? What does it mean to have a mind?

- 4. Theories of mind and consciousness

- 5. Study plan Substance dualism Identity theory Functionalism

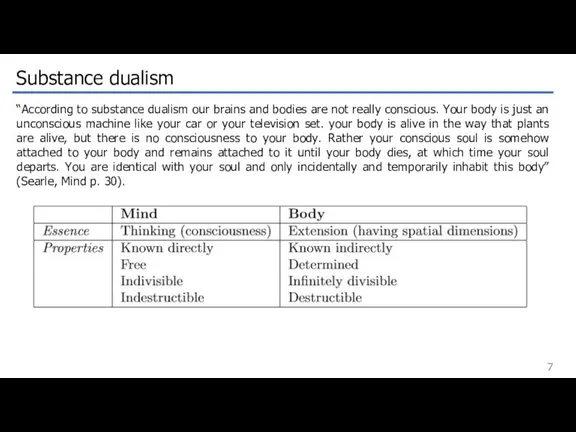

- 6. Substance dualism The mind and body are two different substances. There are two fundamental kinds of

- 7. Substance dualism “According to substance dualism our brains and bodies are not really conscious. Your body

- 8. Argument from doubt Dualism Premise 1. I can doubt the existence of my body. Premise 2.

- 9. Objections Just because Descartes can think of his mind existing without his body, this doesn’t mean

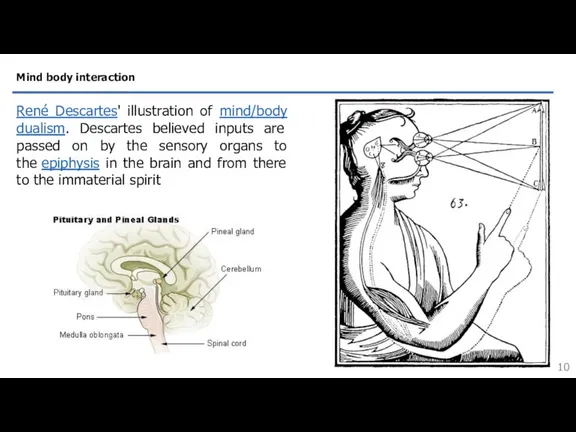

- 10. Mind body interaction René Descartes' illustration of mind/body dualism. Descartes believed inputs are passed on by

- 11. Animals are mindless mechanical automatons

- 12. Privacy and First Person Authority If I desire an apple, I know that I have this

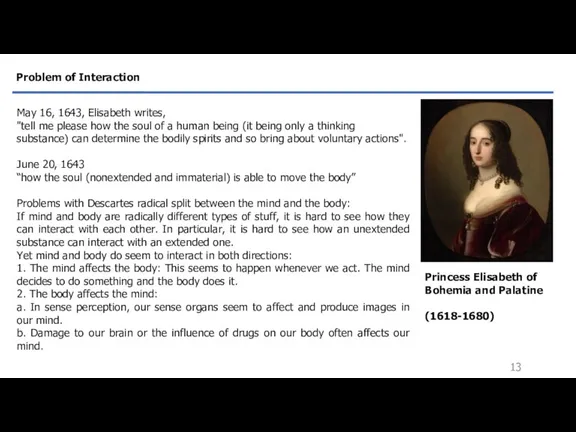

- 13. Problem of Interaction May 16, 1643, Elisabeth writes, "tell me please how the soul of a

- 14. Mental causes If the mind is just thought, not in space, and matter is just extension,

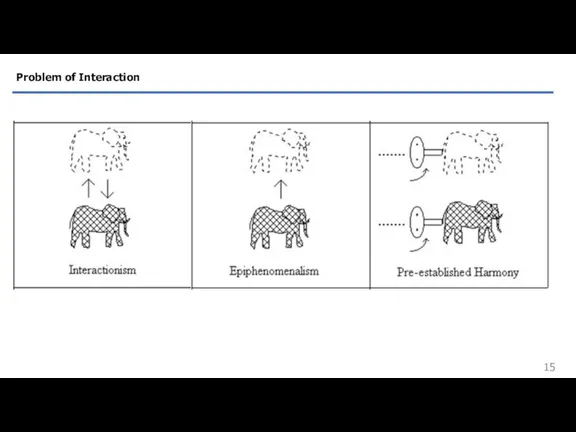

- 15. Problem of Interaction

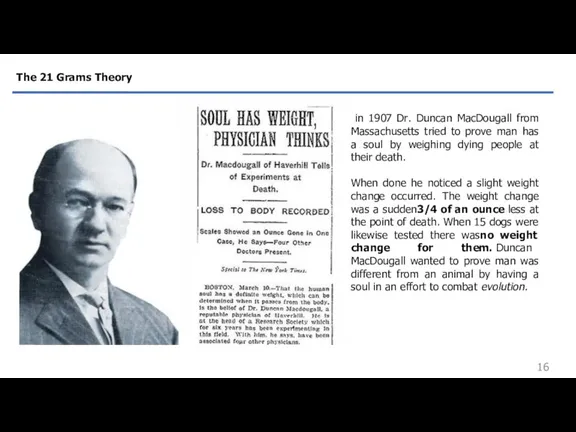

- 16. in 1907 Dr. Duncan MacDougall from Massachusetts tried to prove man has a soul by weighing

- 17. The 21 Grams Theory

- 18. Problem of Interaction The Queerness of the Mental First Person Authority Problems for Dualism

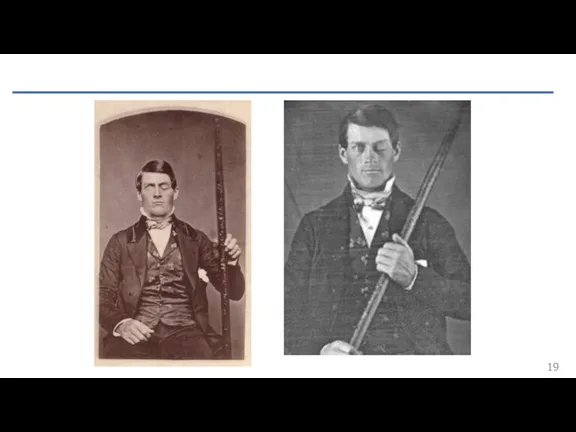

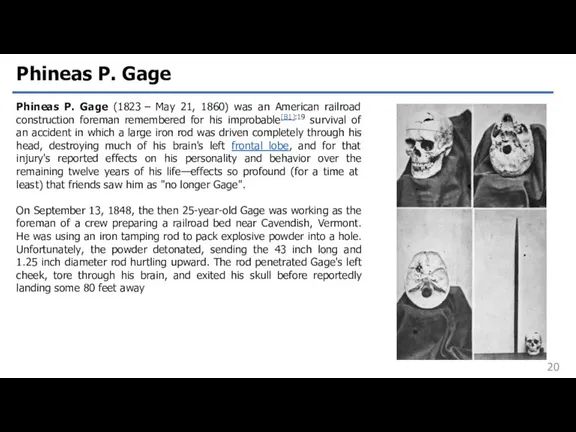

- 20. Phineas P. Gage Phineas P. Gage (1823 – May 21, 1860) was an American railroad construction

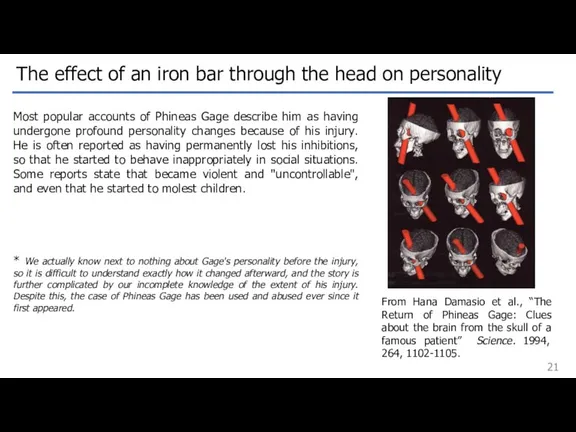

- 21. The effect of an iron bar through the head on personality Most popular accounts of Phineas

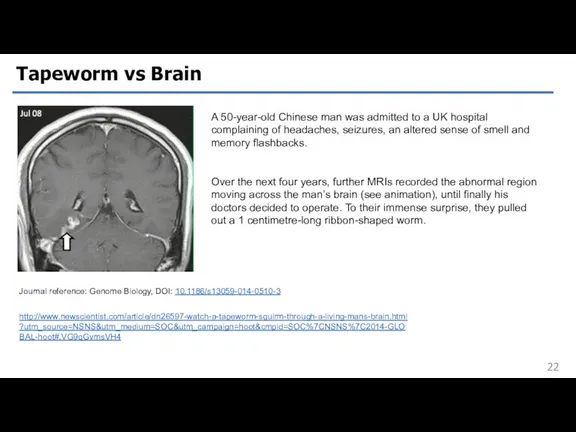

- 22. Tapeworm vs Brain Journal reference: Genome Biology, DOI: 10.1186/s13059-014-0510-3 http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn26597-watch-a-tapeworm-squirm-through-a-living-mans-brain.html?utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=SOC&utm_campaign=hoot&cmpid=SOC%7CNSNS%7C2014-GLOBAL-hoot#.VG9qGvmsVH4 A 50-year-old Chinese man was admitted

- 23. Physicalism Physicalism is the thesis that everything is physical, or as contemporary philosophers sometimes put it,

- 24. Physicalism or materialism? Materialism Materialism – only matter exists -> -> philosophy of mind: mind is

- 25. The Mind/Brain Identity Theory The identity theory of mind holds that states and processes of the

- 26. Identity Theory Identity theory is a family of views on the relationship between mind and body.

- 27. Identity Theory “Pain” and “the firing of C-fibres” both refer to the same thing. Compare Water

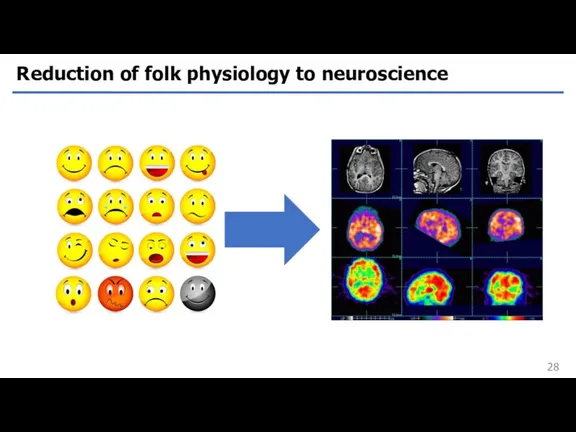

- 28. Reduction of folk physiology to neuroscience

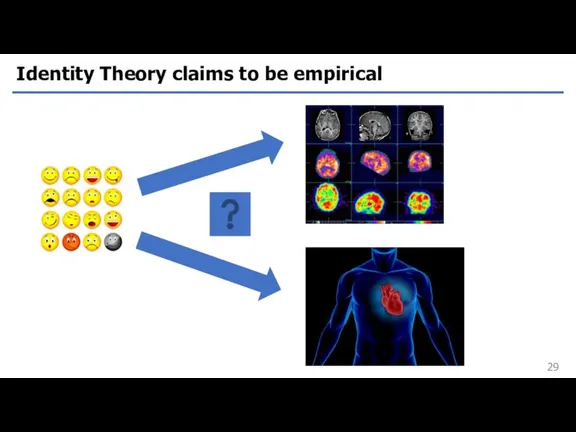

- 29. Identity Theory claims to be empirical

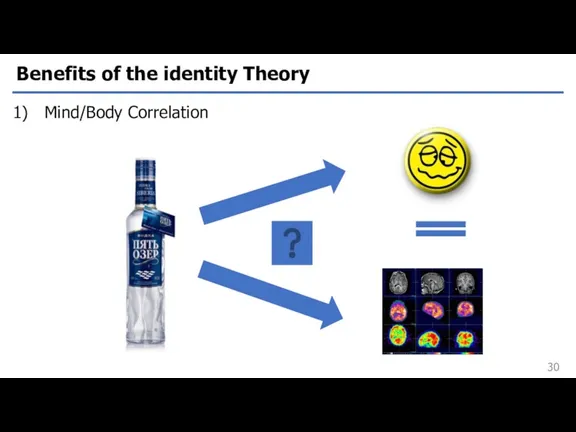

- 30. Benefits of the identity Theory Mind/Body Correlation

- 31. Benefits of the identity Theory 2) Historical parallels: commonsense phenomena have often been reduced by biology,

- 32. Objections to the identity theory What is it like to be a bat? Thomas Nagel (1937-)

- 33. Objections to the identity theory Mental states appear to have many properties that physical states lack

- 34. Objections to the identity theory 2) Philosophical zombies (David Chalmers) A philosophical zombie or p-zombie in

- 35. Philosophical zombies responses Circularity. To believe in P-zombie is to believe that identity theory is fals.

- 36. Objections to the identity theory 3) Multiple realizability Mental properties cannot be identical to physical properties

- 37. Multiple realizability The multiple-realizability thesis implies that mental types and physical types are correlated one-many not

- 38. Multiple realizability Mental types are multiply realizable; If mental types are multiply realizable, then they are

- 39. Functionalism According to functionalism, mental states are identified by what they do rather than by what

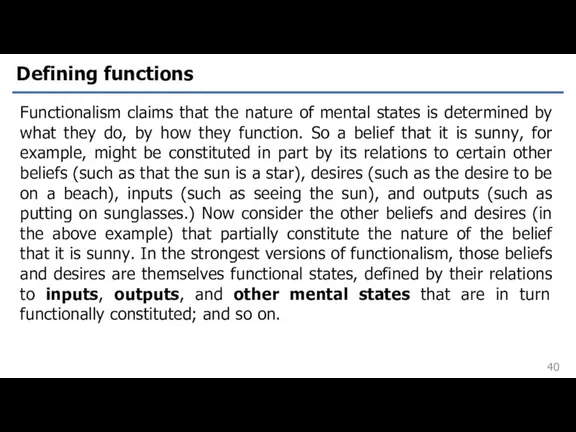

- 40. Defining functions Functionalism claims that the nature of mental states is determined by what they do,

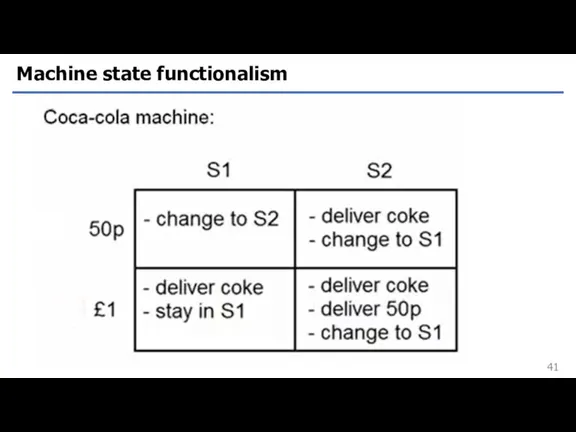

- 41. Machine state functionalism

- 42. Cartesian theater

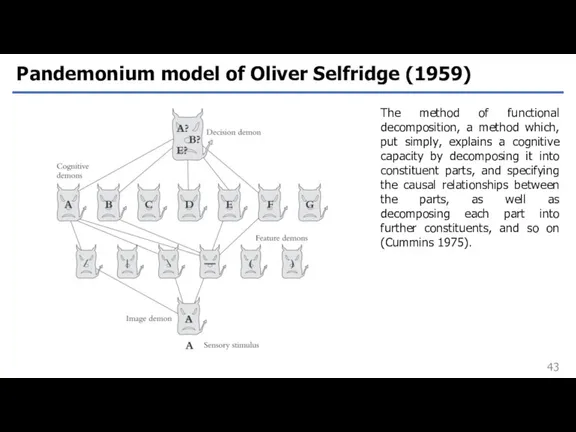

- 43. Pandemonium model of Oliver Selfridge (1959) The method of functional decomposition, a method which, put simply,

- 44. Turing Test (“The Imitation Game”)

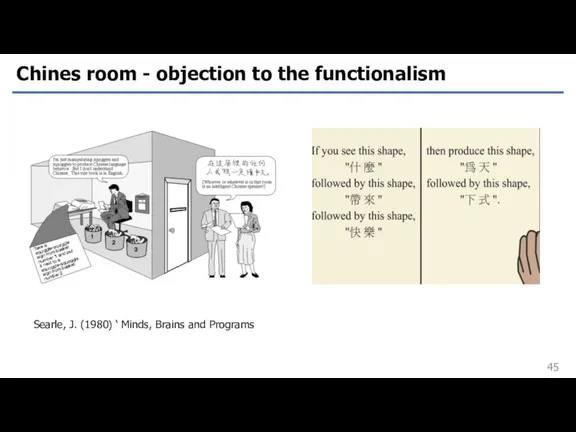

- 45. Chines room - objection to the functionalism Searle, J. (1980) ‘ Minds, Brains and Programs

- 47. Скачать презентацию

Посткласичний період розвитку західноєвропейської філософії xix – xx ст

Посткласичний період розвитку західноєвропейської філософії xix – xx ст Философия Древнего Рима

Философия Древнего Рима Философия Средних веков и эпохи Возрождения

Философия Средних веков и эпохи Возрождения Мораль и ее роль в обществе

Мораль и ее роль в обществе Мыслители, философы, учёные. Материалы для подготовки к олимпиаде по обществознанию

Мыслители, философы, учёные. Материалы для подготовки к олимпиаде по обществознанию Рене Декарт

Рене Декарт Исторические факты зарождения этики, как науки о морали и нравственности

Исторические факты зарождения этики, как науки о морали и нравственности Истина и её критерии

Истина и её критерии Демокріт- давньогрецький філософ

Демокріт- давньогрецький філософ The influence of philosophers on the policies of Barack Obama

The influence of philosophers on the policies of Barack Obama Общество

Общество Трудовая деятельность. Урок обществознания в 10 классе

Трудовая деятельность. Урок обществознания в 10 классе Философы и мыслители

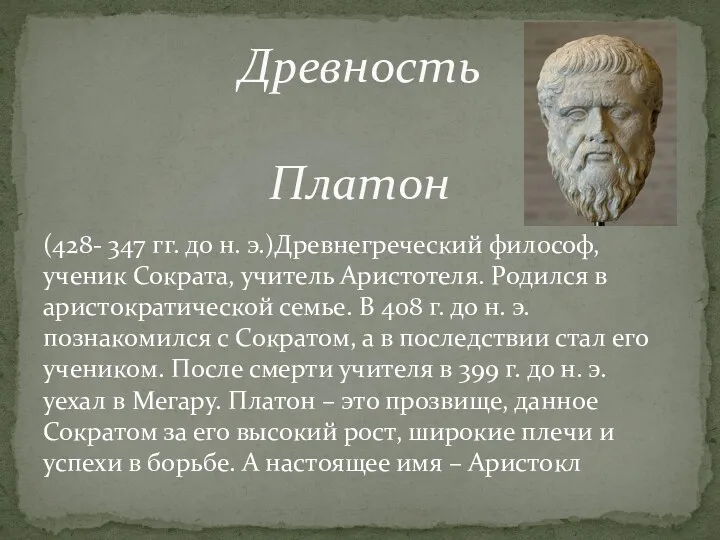

Философы и мыслители Этапы развития античной философии

Этапы развития античной философии Мировоззрение

Мировоззрение Общество (динамический анализ)

Общество (динамический анализ) Русская философия. Характеристика основных идей русских философов

Русская философия. Характеристика основных идей русских философов Гносеология. Проблема познания в философии

Гносеология. Проблема познания в философии Учение буддизм

Учение буддизм Деятельность и ее виды

Деятельность и ее виды Глобальные проблемы человечества

Глобальные проблемы человечества Культура и цивилизация. (Лекция 12)

Культура и цивилизация. (Лекция 12) Содержание и формы духовной деятельности (10 класс)

Содержание и формы духовной деятельности (10 класс) Сократ. Философские взгляды Сократа

Сократ. Философские взгляды Сократа Проблемы человека и его свободы в экзистенциализме. Жан Поль, Сартр, Альбер Камю

Проблемы человека и его свободы в экзистенциализме. Жан Поль, Сартр, Альбер Камю Бытие и сознание человека

Бытие и сознание человека Предмет и основные концепции современной философии науки

Предмет и основные концепции современной философии науки Познание. Процесс получения знаний

Познание. Процесс получения знаний