Содержание

- 2. 1. Early Middle Ages (600–1066)

- 3. Political history

- 4. At the start of the Middle Ages, England was a part of Britannia, a former province

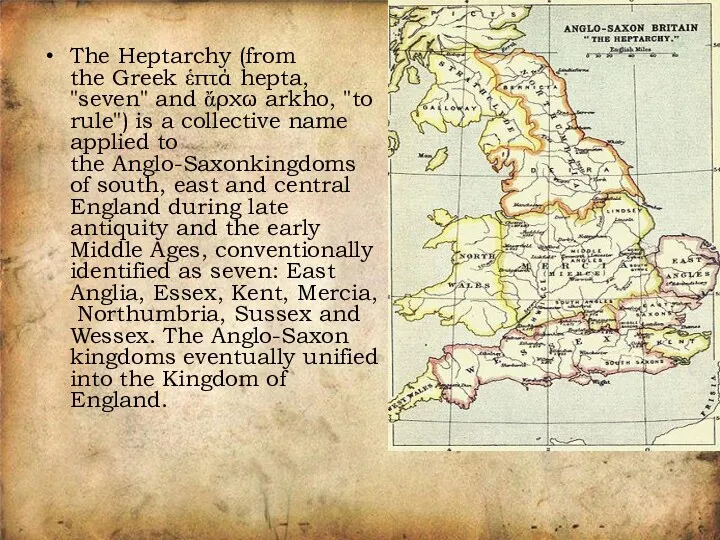

- 5. The Heptarchy (from the Greek ἑπτά hepta, "seven" and ἄρχω arkho, "to rule") is a collective

- 6. In the 7th century, the kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence under the leadership of King

- 7. Stained glass window in the cloister of Worcester Cathedral representing the death of Penda of Mercia

- 8. In 789, however, the first Scandinavian raids on England began. Mercia and Northumbria fell in 875

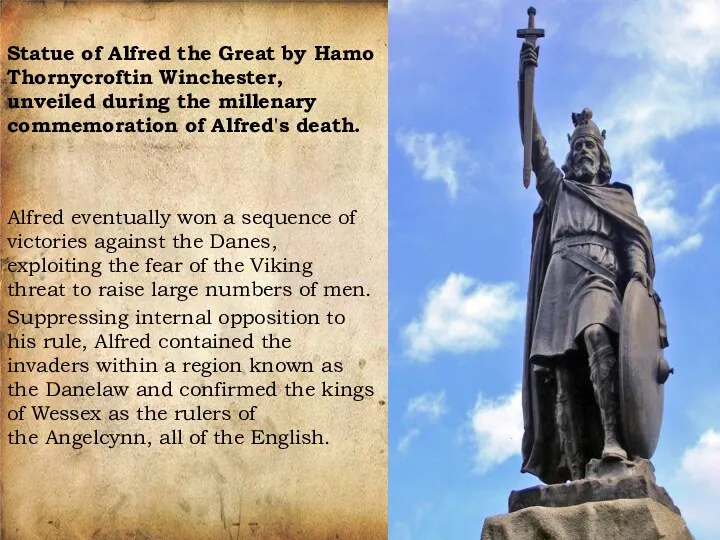

- 9. Statue of Alfred the Great by Hamo Thornycroftin Winchester, unveiled during the millenary commemoration of Alfred's

- 10. Wessex expanded further north into Mercia and the Danelaw, and by the 950s and the reigns

- 11. With the death of Edgar, however, the royal succession became problematic. Æthelred took power in 978

- 12. Sweyn Forkbeard Sweyn Forkbeard was king of Denmark, England, and parts of Norway. His name appears

- 13. Æthelred's son, Edward the Confessor, had survived in exile in Normandy and returned to claim the

- 14. Harold II (or Harold Godwinson; Old English: Harold Godƿinson) was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England.

- 15. Government and society

- 16. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were hierarchical societies, each based on ties of allegiance between powerful lords and

- 18. Freemen, called churls, formed the next level of society, often holding land in their own right

- 20. The Anglo-Saxon kings built up a set of written laws, issued either as statutes or codes,

- 22. High Middle Ages (1066–1272)

- 24. Political history

- 25. In 1066, William, the Duke of Normandy, took advantage of the English succession crisis to invade.

- 26. The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of Duke

- 27. Some Norman lords used England as a launching point for attacks into South and North Wales,

- 28. Norman rule, however, proved unstable; successions to the throne were contested, leading to violent conflicts between

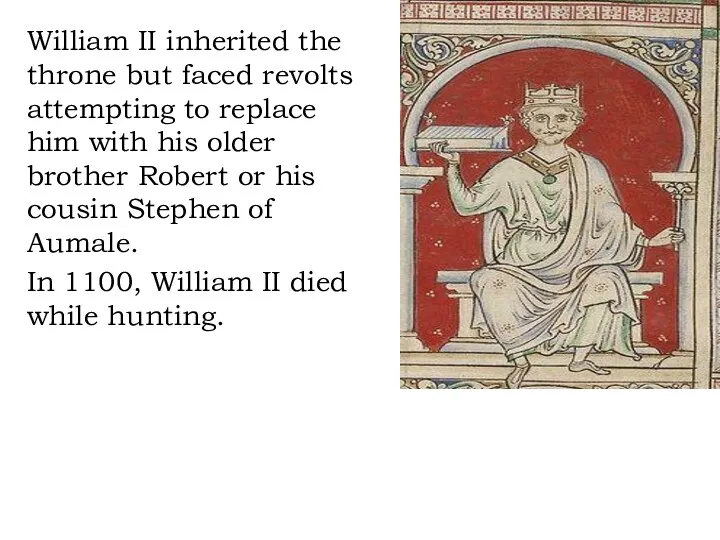

- 29. William II inherited the throne but faced revolts attempting to replace him with his older brother

- 30. Despite Robert's rival claims, his younger brother Henry I immediately seized power. War broke out, ending

- 31. Henry's only legitimate son, William, died aboard the White Ship disaster of 1120, sparking a fresh

- 32. The White Ship was a vessel that sank in the English Channel near the Normandy coast

- 33. Civil war broke out across England and Normandy, resulting in a long period of warfare later

- 34. Henry II was the first of the Angevin rulers of England, so-called because he was also

- 35. Henry reasserted royal authority and rebuilt the royal finances, intervening to claim power in Ireland and

- 36. Richard spent his reign focused on protecting his possessions in France and fighting in the Third

- 37. John's efforts to raise revenues, combined with his fractious relationships with many of the English barons,

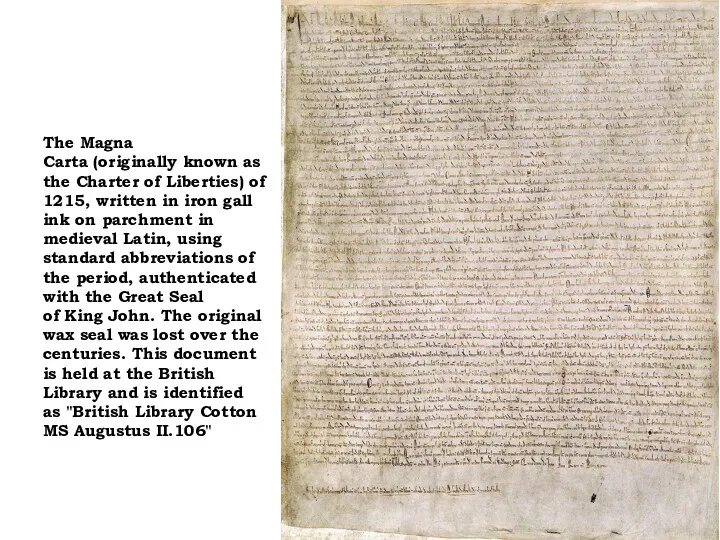

- 38. The Magna Carta (originally known as the Charter of Liberties) of 1215, written in iron gall

- 39. John died having fought the rebel barons and their French backers to a stalemate, and royal

- 40. Government and society

- 41. Within twenty years of the Norman conquest, the former Anglo-Saxon elite were replaced by a new

- 42. Domesday Book is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts

- 43. The method of government after the conquest can be described as a feudal system, in that

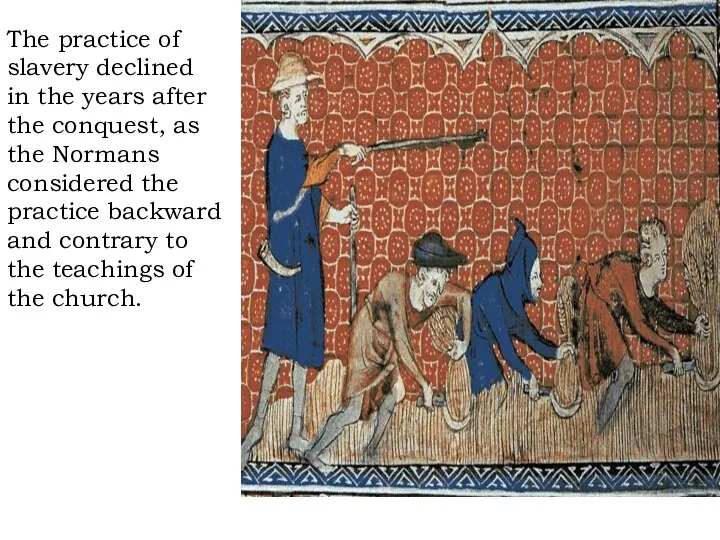

- 44. The practice of slavery declined in the years after the conquest, as the Normans considered the

- 45. At the centre of power, the kings employed a succession of clergy as chancellors, responsible for

- 46. Many tensions existed within the system of government Property and wealth became increasingly focused in the

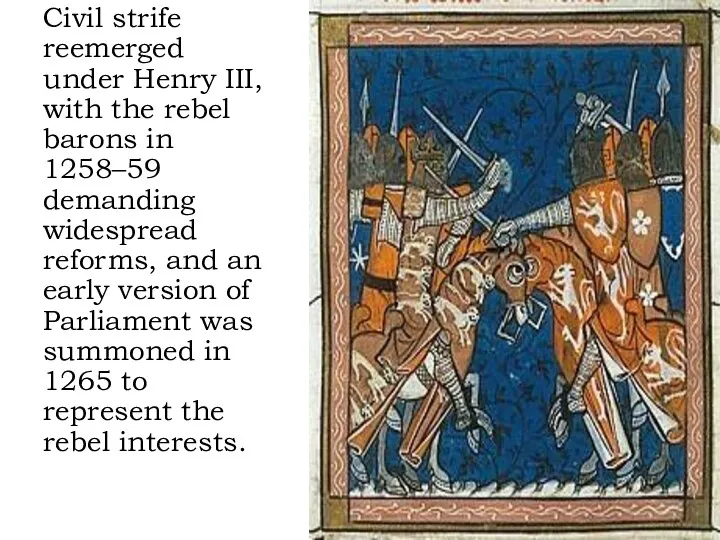

- 47. Civil strife reemerged under Henry III, with the rebel barons in 1258–59 demanding widespread reforms, and

- 48. Late Middle Ages (1272–1485)

- 49. Political history

- 50. On becoming king, Edward I rebuilt the status of the monarchy, restoring and extending key castles

- 51. Edward also fought campaigns in Scotland, but was unable to achieve strategic victory, and the costs

- 52. Edward II inherited the war with Scotland and faced growing opposition to his rule as a

- 53. Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King

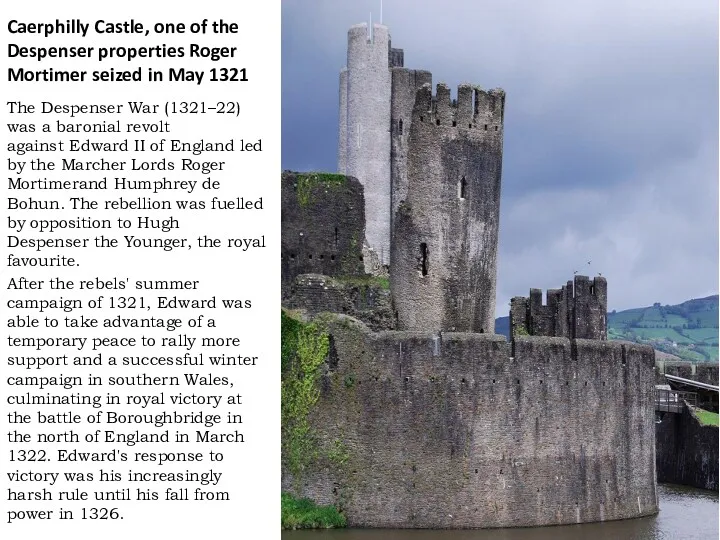

- 54. Caerphilly Castle, one of the Despenser properties Roger Mortimer seized in May 1321 The Despenser War

- 55. Like his grandfather, Edward III took steps to restore royal power, but during the 1340s the

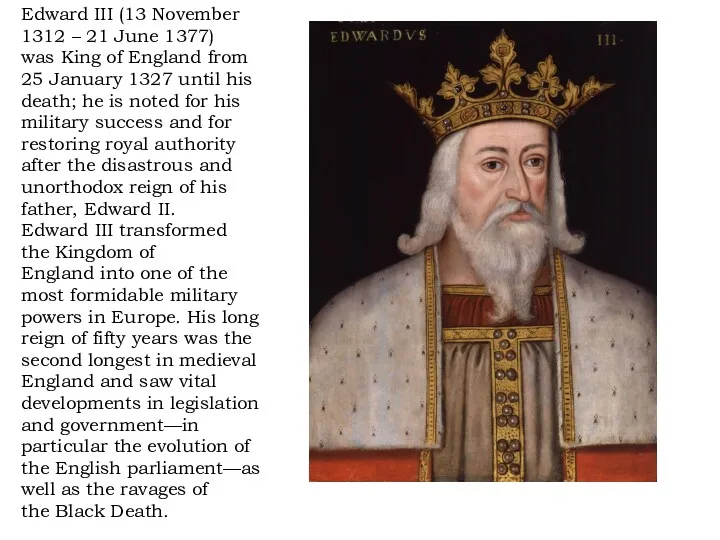

- 56. Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377) was King of England from 25 January

- 57. Edward's grandson, the young Richard II, faced political and economic problems, many resulting from the Black

- 58. Henry of Bolingbroke (15 April 1367[1] – 20 March 1413) born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire,

- 59. Ruling as Henry IV, he exercised power through a royal council and parliament, while attempting to

- 60. A sequence of bloody civil wars, later termed the Wars of the Roses, finally broke out

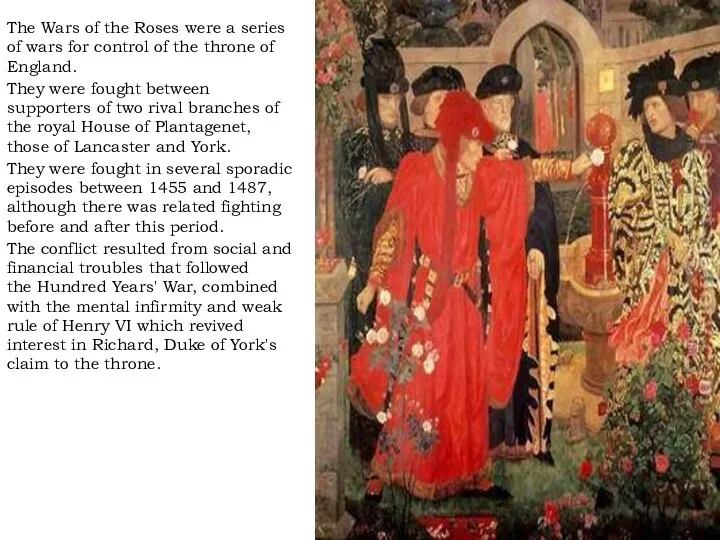

- 61. The Wars of the Roses were a series of wars for control of the throne of

- 62. The White Rose of the House of York The Red Rose of theHouse of Lancaster

- 63. The name Wars of the Roses refers to the heraldic badges associated with the two royal

- 64. By 1471 Edward was triumphant and most of his rivals were dead. On his death, power

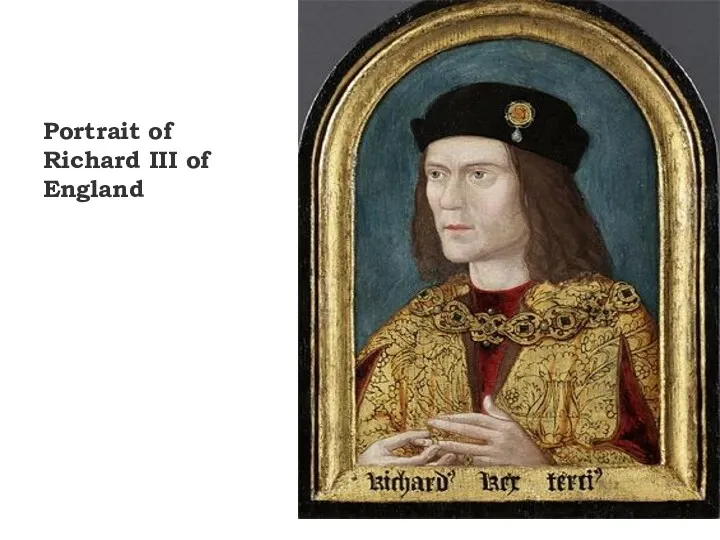

- 65. Portrait of Richard III of England

- 66. Government and society

- 67. On becoming king in 1272, Edward I reestablished royal power, overhauling the royal finances and appealing

- 68. Edward used Parliament even more than his predecessors to handle general administration, to legislate and to

- 69. Society and government in England in the early 14th century were challenged by the Great Famine

- 70. A poll tax was introduced in 1377 that spread the costs of the war in France

- 71. By the time that Richard II was deposed in 1399, the power of the major noble

- 73. Скачать презентацию

![Henry of Bolingbroke (15 April 1367[1] – 20 March 1413)](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/246746/slide-57.jpg)

Франция в XVIII в. Причины и начало Французской революции

Франция в XVIII в. Причины и начало Французской революции Истоки химии. Алхимия

Истоки химии. Алхимия Гражданская война в США

Гражданская война в США презентация по истории России

презентация по истории России Скифы: культура и история

Скифы: культура и история Вывод Советских войск из .Афганистана

Вывод Советских войск из .Афганистана Место и роль Руси в Европе

Место и роль Руси в Европе Оформление стендов, фотоальбомов и других материалов для передачи в школьный краеведческий музей

Оформление стендов, фотоальбомов и других материалов для передачи в школьный краеведческий музей Al doilea război mondial (1939-1945). Ofensiva statelor agresoare

Al doilea război mondial (1939-1945). Ofensiva statelor agresoare Образ Александра Невского в искусстве

Образ Александра Невского в искусстве Культура архаической Греции (VIII в.- к. VI в. до н.э.)

Культура архаической Греции (VIII в.- к. VI в. до н.э.) У Победы множество имен Ковровчане – участники Великой Отечественной войны

У Победы множество имен Ковровчане – участники Великой Отечественной войны Гетьманщина в роки правління Івана Виговського та Юрія Хмельницького. Доба Руїни

Гетьманщина в роки правління Івана Виговського та Юрія Хмельницького. Доба Руїни Государство на берегах Нила

Государство на берегах Нила Бессмертие и сила Ленинграда

Бессмертие и сила Ленинграда Испания туралы мәлімет

Испания туралы мәлімет Декоративное искусство Древней Греции

Декоративное искусство Древней Греции Катастрофа на Чорнобильській АЕС

Катастрофа на Чорнобильській АЕС Интеллектуальная игра по истории СЛАВА РОССИИ

Интеллектуальная игра по истории СЛАВА РОССИИ Истоки современной архитектуры. История современной архитектуры

Истоки современной архитектуры. История современной архитектуры Проект Кто твой герой. Мы помним и гордимся

Проект Кто твой герой. Мы помним и гордимся Смута в России в начале XVII века

Смута в России в начале XVII века Исторические сведения о готах

Исторические сведения о готах История книги

История книги Восстание декабристов

Восстание декабристов Культура Древнего Египта. 6 класс

Культура Древнего Египта. 6 класс Древняя Индия

Древняя Индия США в эпоху позолоченного века

США в эпоху позолоченного века