Содержание

- 2. Qualitative or quantitative methods? Quantitative methods lose some accuracy in measurement. Measure not all the features

- 3. Features of qualitative research Inductive view of relationship between theory and research theories and concepts emerge

- 4. Grounded theory Not actually a theory in itself, it is rather an approach to generating theory

- 5. Research methods used in qualitative research Ethnography / participation observation prolonged immersion in the field Qualitative

- 6. When qualitative methods? If we study uniqueness, a particular social object, the study of the overall

- 7. The main steps of qualitative research

- 8. Concepts in qualitative research Blumer (1954) argued against the use of definitive concepts in qualitative research:

- 9. Approaches to reliability and validity 1. Adapting concepts from quantitative research little change of meaning quality,

- 10. 2. Alternative criteria (Guba & Lincoln, 1994) Trustworthiness Credibility (a parallel for internal validity) Dependability (a

- 11. What is action research? An authentic research method dealing with real problems within an organization Designed

- 12. 3. Midway position (Hammersley, 1992) ‘Validity’ criterion needs to be reformulated: Empirical account must be plausible

- 13. Triangulation & validation Triangulation - use of more than one method. If in the case of

- 14. The main preoccupations of qualitative researchers 1 Seeing through the eyes of those studied Taking the

- 15. The main preoccupations of qualitative researchers 2 Emphasis on social process How patterns of events unfold

- 16. Criticisms of qualitative research Too subjective Researcher decides what to focus on Difficult to replicate Unstructured

- 17. Is it always like this? Some qualitative research departs from these conventions: Focused on a specific

- 18. Contrasting qualitative and quantitative research

- 19. Similarities between quantitative and qualitative research The concern with data reduction The concern with answering research

- 20. Differences between structured and qualitative interviews Qualitative interviews… are less structured/standardized, take the participant’s viewpoint, encourage

- 21. Unstructured or semi-structured? Unstructured interview Few, loosely defined topics Open-ended questions to allow free response Conversational

- 22. Types of interview Informal (allows the researcher to go with the flow and create impromptu questions

- 23. Preparing an interview guide Have a logical but flexible order of topics. Focus on research questions:

- 24. Preparing for the interview Make yourself familiar with the interviewee’s world, so that you will be

- 25. Kvale’s criteria of a successful interviewer Knowledgeable: familiar with the focus of the interview. Structuring: gives

- 26. Make notes after the interview How did the interview go (was interviewee talkative, cooperative, nervous, well-dressed/scruffy,

- 27. Formulating questions for an interview guide

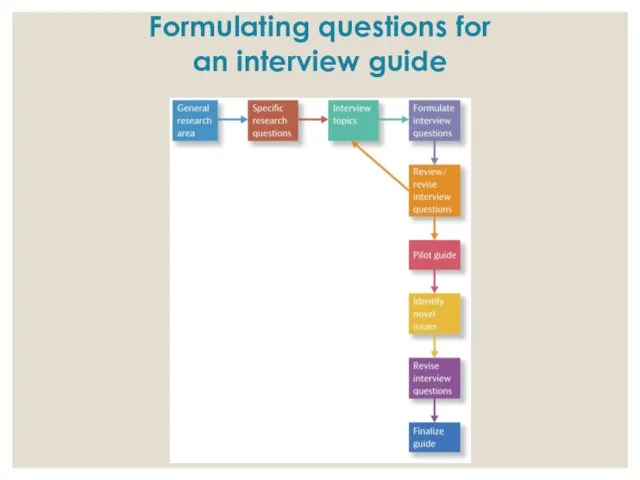

- 28. Interview Format and Types of Questions Background information includes such personal information as demographics (e.g., age,

- 29. Interview Format and Types of Questions 2 The third part of the interview should explore the

- 30. Kinds of questions (Kvale 1996) Introducing (“Tell me about…”) Follow-up (“What do you mean by that?”)

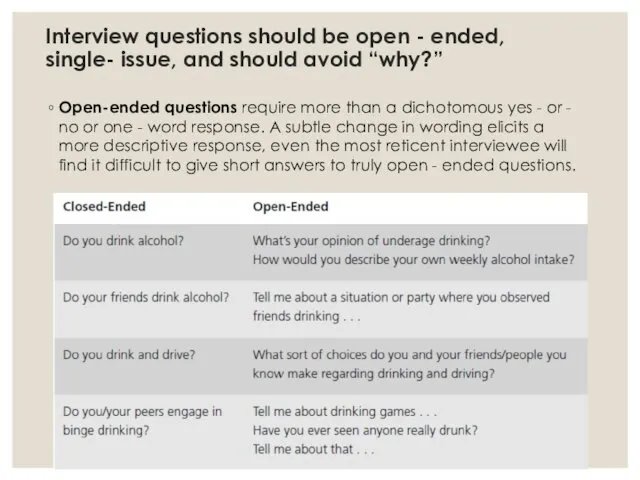

- 31. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?” Open-ended questions require

- 32. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?” 2 Interview questions,

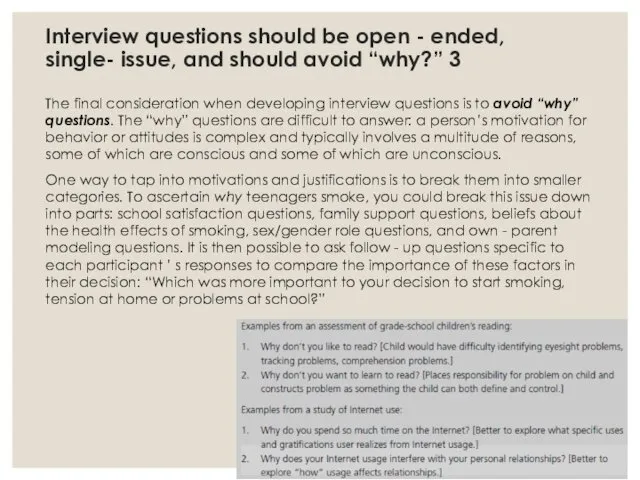

- 33. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?” 3 The final

- 34. Prompts Interviewers need not rely on the interview guide alone and other material can be used

- 35. Sequencing Each interview requires a set up, the building of rapport, and a closing. Each of

- 36. Recording and transcription Audio-recording and transcribing: Researcher is not distracted by note-taking. Can focus on listening

- 37. Telephone interviewing Many advantages to conducting interviews via telephone. Cost – it is much cheaper and

- 38. Special types of qualitative interview Life history interview Subject looks back across their entire life. Reveals

- 39. Online interviewing Online personal interviews for qualitative research Textual in nature: email exchanges, direct messaging, forums.

- 40. Using Skype A form of synchronous interview conducted via webcams available through PCs, tablets, and smartphones.

- 41. Advantages of participant observation over qualitative interviewing Seeing through others’ eyes Learning the native language Taken

- 42. Advantages of qualitative interviewing over participant observation Finding out about issues resistant to observation Interviewees reflect

- 44. Скачать презентацию

Ключови компетентности европейска референтна рамка

Ключови компетентности европейска референтна рамка Особенности, проблемы и возможные альтернативы развития российского общества

Особенности, проблемы и возможные альтернативы развития российского общества Черская библиотека - социокультурный центр

Черская библиотека - социокультурный центр Социологическая концепция М. Вебера (1864-1920)

Социологическая концепция М. Вебера (1864-1920) Итоги за 2016 год и планы на 2017 год ресурсного центра для НКО в ЮВАО Вешняки

Итоги за 2016 год и планы на 2017 год ресурсного центра для НКО в ЮВАО Вешняки Краткая история развития социальной работы

Краткая история развития социальной работы Ценностные приоритеты моего поколения

Ценностные приоритеты моего поколения Природний рух населення

Природний рух населення Опасный путь преступной жзни

Опасный путь преступной жзни Нации и межнациональные отношения

Нации и межнациональные отношения Тренажер: подготовка к ЕГЭ по обществознанию (задания части А)

Тренажер: подготовка к ЕГЭ по обществознанию (задания части А) Модель соціальної політики. Німецька модель. Австрія

Модель соціальної політики. Німецька модель. Австрія Представлення отриманих даних

Представлення отриманих даних Реализация социальных практик и общественных инициатив по направлениям РДШ в образовательном учреждении

Реализация социальных практик и общественных инициатив по направлениям РДШ в образовательном учреждении Культура и субкультура. Специфика молодёжной субкультуры

Культура и субкультура. Специфика молодёжной субкультуры Шаг вперед ресоциализация и интеграция в социум лиц, освободившихся из мест лишения свободы

Шаг вперед ресоциализация и интеграция в социум лиц, освободившихся из мест лишения свободы Трансформація інституту зайнятості, як складова глобальних змін у соціально-трудовій сфері. Феномен прекаризації

Трансформація інституту зайнятості, як складова глобальних змін у соціально-трудовій сфері. Феномен прекаризації Основные понятия

Основные понятия Выявление уровня осведомлённости людей об инклюзивном туризме

Выявление уровня осведомлённости людей об инклюзивном туризме Формирование социологической выборки. Типы выборок

Формирование социологической выборки. Типы выборок Чистый поселок. Волонтёрский отряд добровольцев, члены детской общественной организации Рука в руке

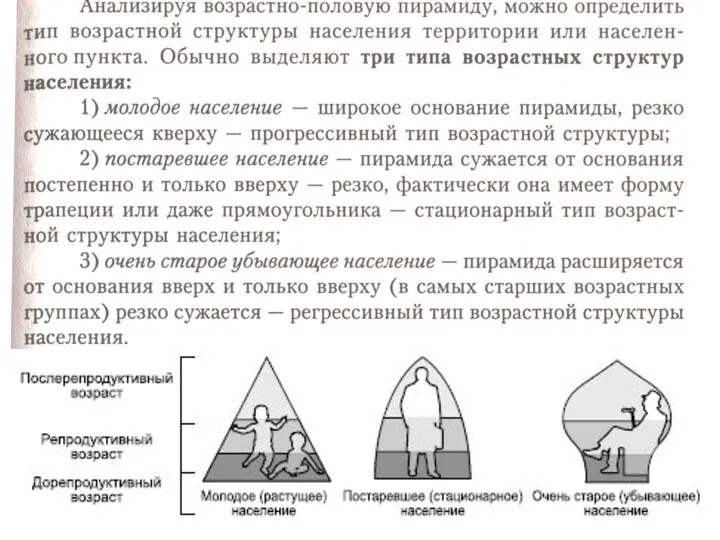

Чистый поселок. Волонтёрский отряд добровольцев, члены детской общественной организации Рука в руке Типы возрастных структур населения

Типы возрастных структур населения Что делает человека человеком

Что делает человека человеком Критическая теория технокапитализма Дугласа Келлнера

Критическая теория технокапитализма Дугласа Келлнера Курс подготовки к экзамену по обществознанию

Курс подготовки к экзамену по обществознанию Презентация к уроку по обществознанию Духовная культура 10 кл.

Презентация к уроку по обществознанию Духовная культура 10 кл. Профбюро Института промышленного менеджмента экономики и торговли (ИПМЭиТ)

Профбюро Института промышленного менеджмента экономики и торговли (ИПМЭиТ) Проблемы и перспективы развития ТСЖ как новые формы социального взаимодействия: социологический анализ

Проблемы и перспективы развития ТСЖ как новые формы социального взаимодействия: социологический анализ