Содержание

- 2. Requirements 4+ homeworks Project Final exam Distribution: 40-20-40 read before class no cheating

- 3. Textbooks J. Gruber "Public Finance and Public Policy," Worth Publishers, 2007 or later editions Russian translation

- 4. Topics 1. Subject and methods of Public Finance. 2. Externalities. Applications to Environment and Health. 3.

- 5. Topics (cont) 6. Social Insurance. Adverse selection and moral hazard. 7. Social security. Unemployment insurance. 8.

- 6. Introduction What is the proper role of government? Expenditure side: What services should the government provide?

- 7. THE FOUR QUESTIONS OF PUBLIC FINANCE When should the government intervene in the economy? How might

- 8. When Should the Government Intervene in the Economy? Normally, private markets are competitive and efficient. Generally

- 9. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures “Problems” for markets: Externalities Private (Asymmetric) Information Small number

- 10. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures In 2003, there were 45 million people without health

- 11. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures Measles epidemic from 1989-1991, caused by low immunization rates

- 12. When Should the Government Intervene? Redistribution Government may care about both the size of the “economic

- 13. When Should the Government Intervene? Redistribution Of the uninsured, for example, roughly three-quarters are in families

- 14. How Might the Government Intervene? If the government wants to intervene in a market, there are

- 15. What Are the Effects of Alternative Interventions? Much of the focus of empirical public finance is

- 16. What Are the Effects of Alternative Interventions? Expanding health insurance Direct effect of government provision of

- 17. The Congressional Budget Office Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides nonpartisan analyses needed for economic decisions of

- 18. Why Do Governments Do What They Do? Governments do not simply behave as benign actors who

- 19. Why Do Governments Do What They Do? For example, substantial variation across developed countries in health

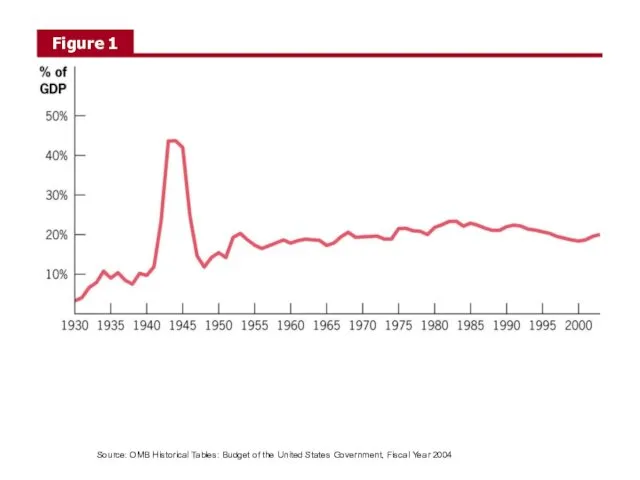

- 20. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT The size and growth of government The “size” of the government is often

- 21. Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

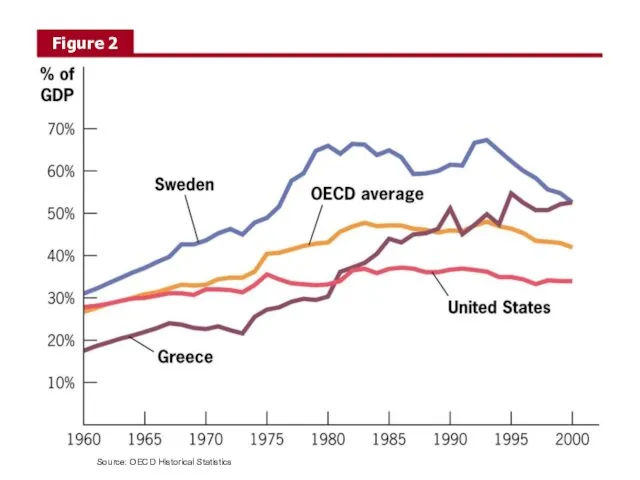

- 22. Source: OECD Historical Statistics

- 23. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Decentralization and budgeting Other features Decentralization: In the United States., local, state and

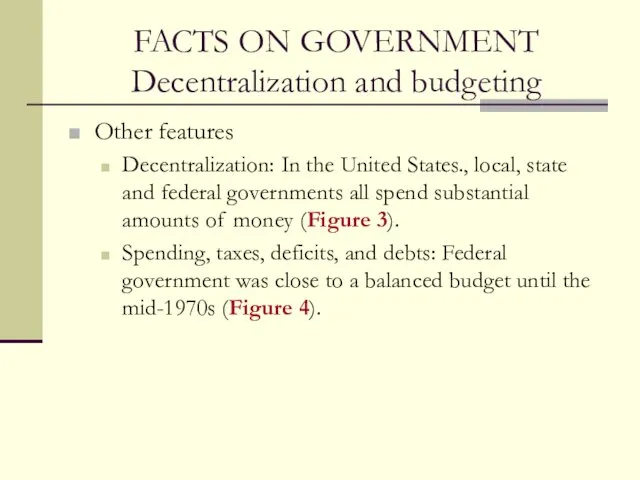

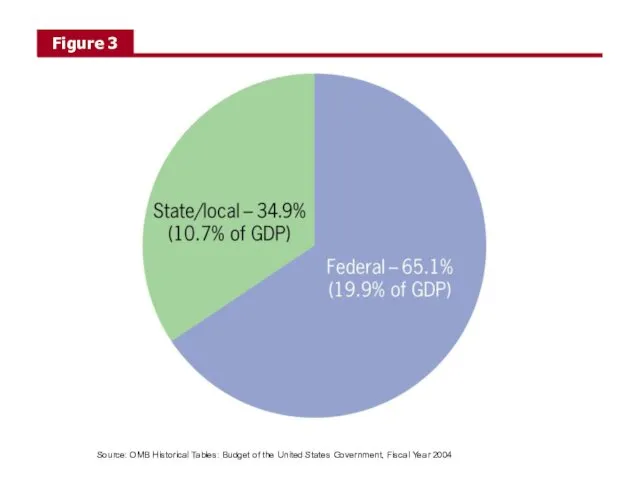

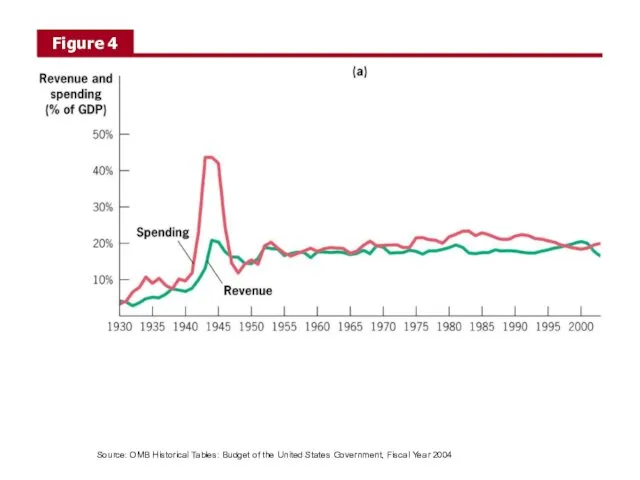

- 24. Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

- 25. Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

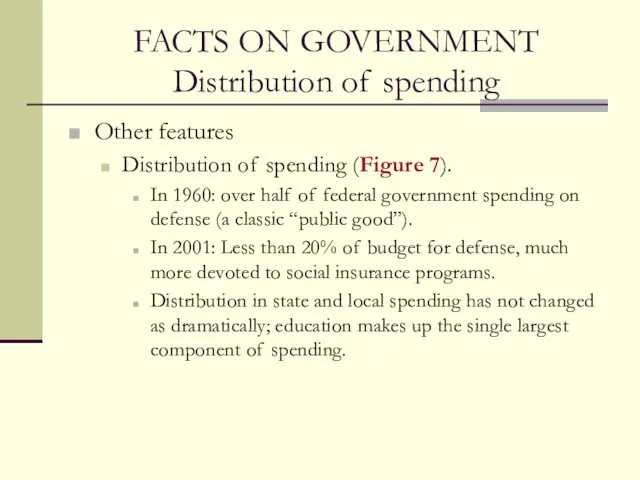

- 26. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of spending Other features Distribution of spending (Figure 7). In 1960: over

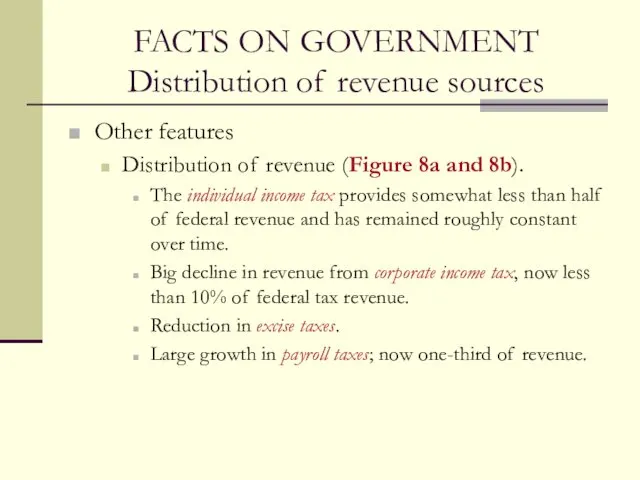

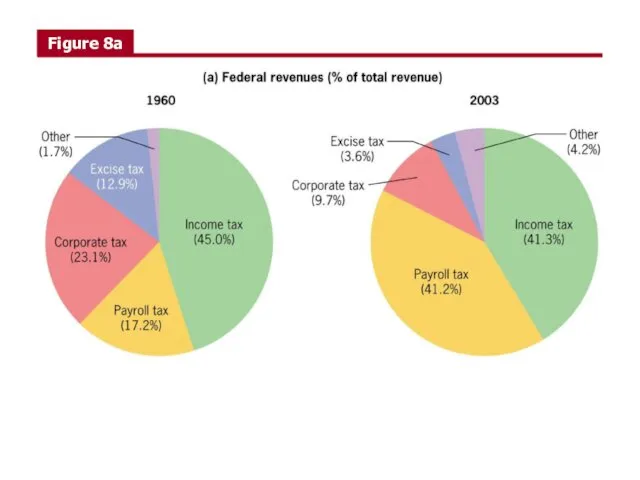

- 28. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of revenue sources Other features Distribution of revenue (Figure 8a and 8b).

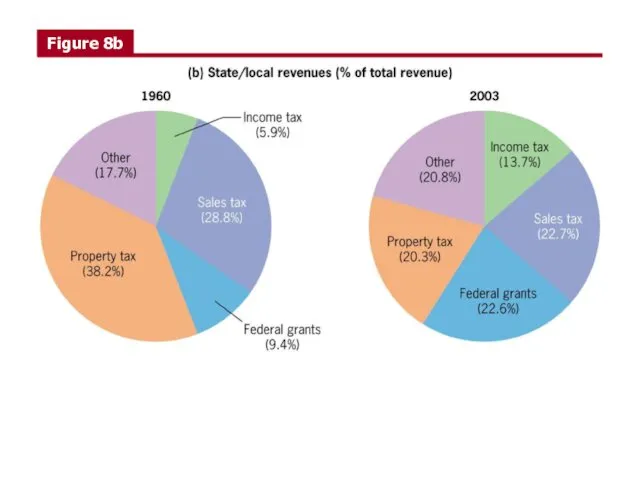

- 29. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of revenue sources Other features Distribution of revenue different at state/local level.

- 32. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Regulatory role of the government Other features Regulatory role–does not usually show up

- 33. Recap Four key questions in public finance When should the government intervene in the economy? How

- 34. Theoretical tools (recap): Income and substitution effects. Equivalent and compensating variations. Consumer surplus. What are the

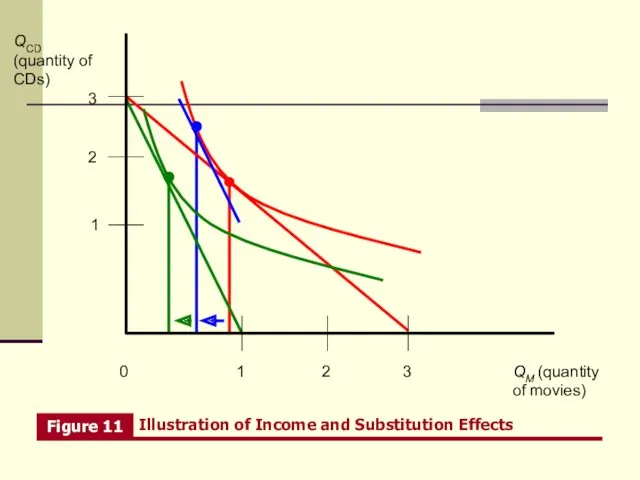

- 35. QM (quantity of movies) QCD (quantity of CDs) 0 1 2 1 2 3 3

- 36. Spectrum auctions: Governments sell licenses to use a certain range of frequencies (electromagnetic spectrum). Many auctions.

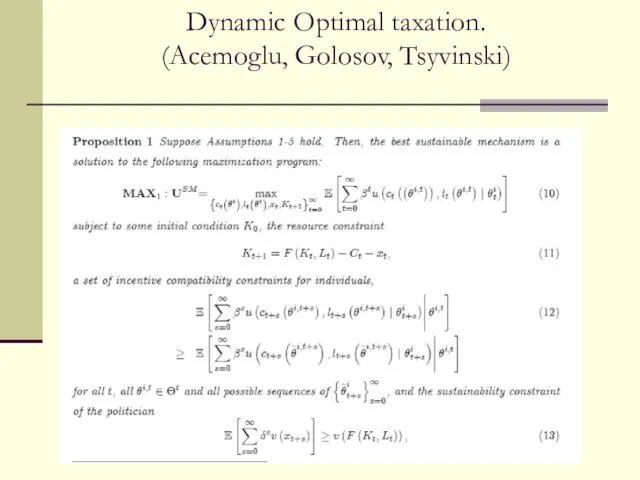

- 37. Dynamic Optimal taxation. (Acemoglu, Golosov, Tsyvinski)

- 38. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK TANF and labor supply among single mothers TANF is “Temporary Assistance

- 39. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK Identifying the budget constraint What does the budget constraint look like?

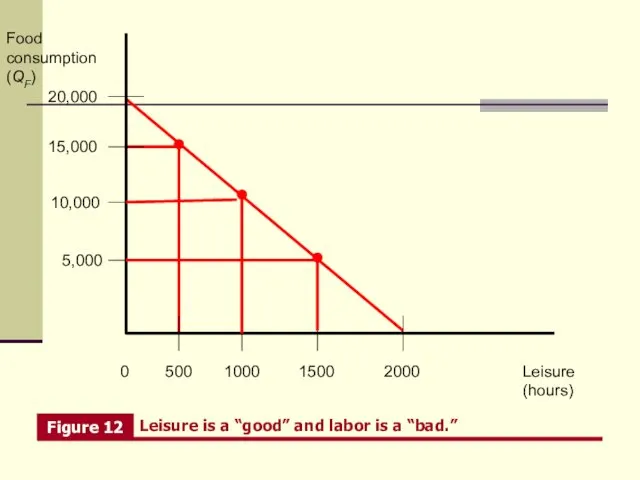

- 40. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK Identifying the budget constraint The “price” of one hour of leisure

- 41. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1000 1500 20,000 2000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000

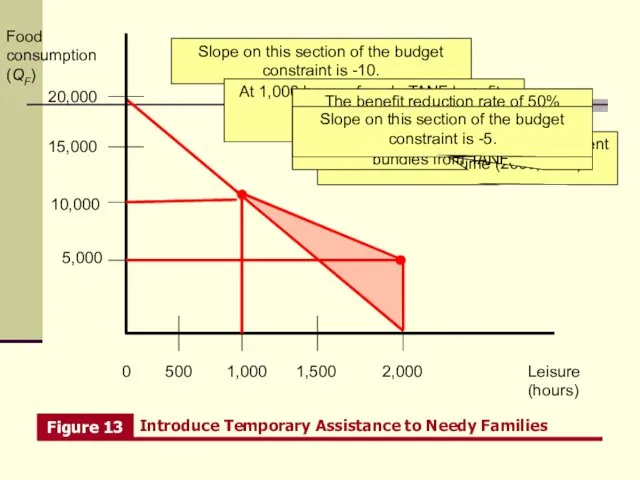

- 42. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of TANF on the budget constraint Now, let’s introduce

- 43. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of TANF on the budget constraint Assume that benefit

- 44. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1,000 1,500 20,000 2,000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000 Slope on

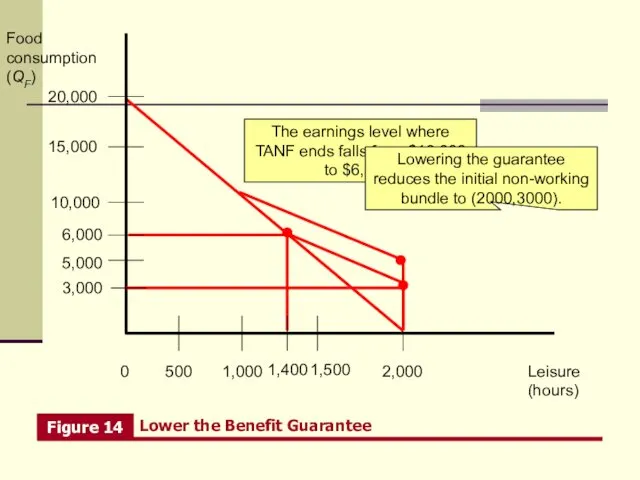

- 45. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of changes in the benefit guarantee One possible “policy

- 46. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1,000 1,500 20,000 2,000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000 3,000 1,400

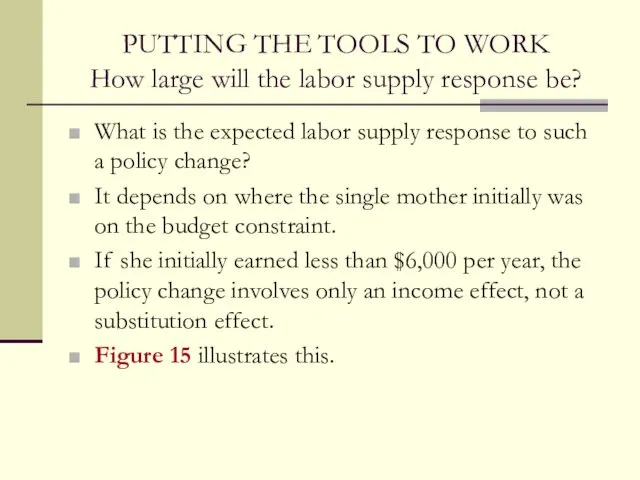

- 47. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be? What is the

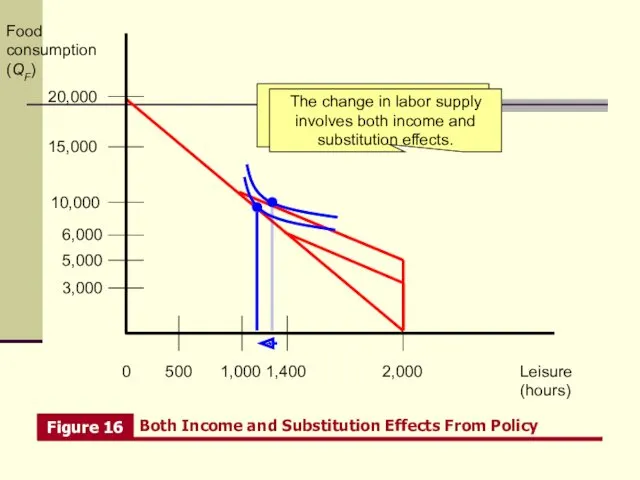

- 48. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1,000 20,000 2,000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000 3,000 1,400 6,000

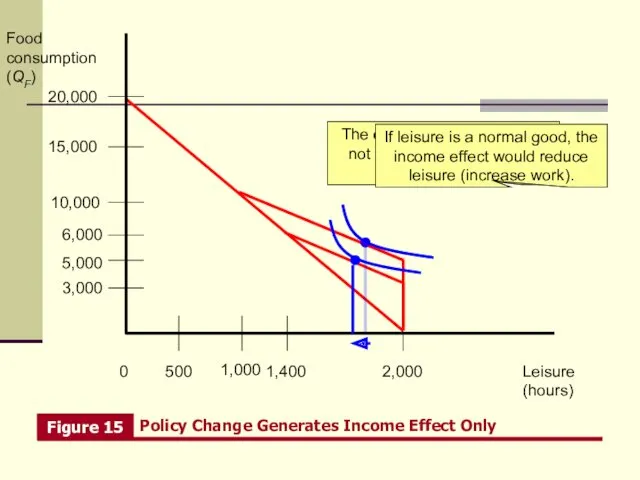

- 49. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be? If she initially

- 50. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1,000 20,000 2,000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000 3,000 1,400 6,000

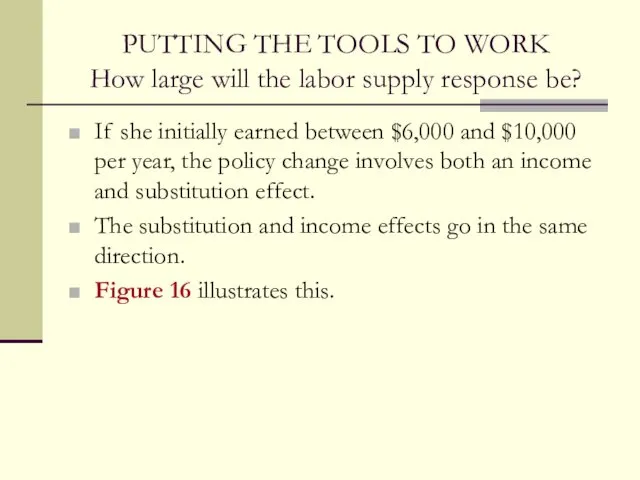

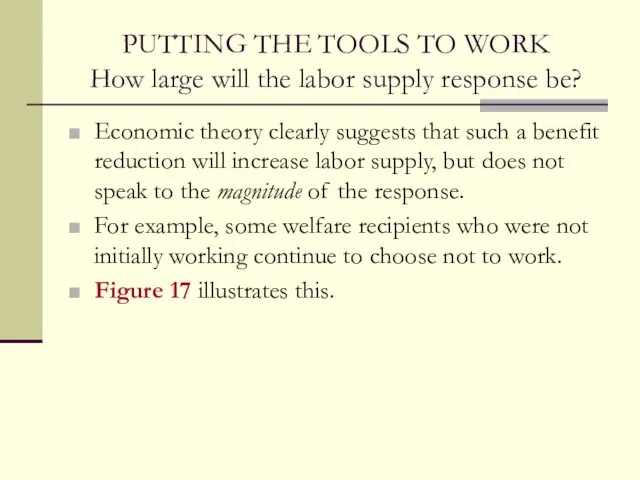

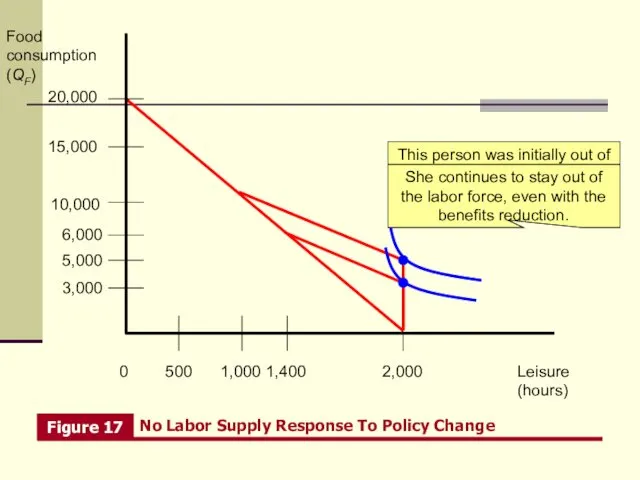

- 51. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be? Economic theory clearly

- 52. Leisure (hours) Food consumption (QF) 0 1,000 20,000 2,000 500 15,000 10,000 5,000 3,000 1,400 6,000

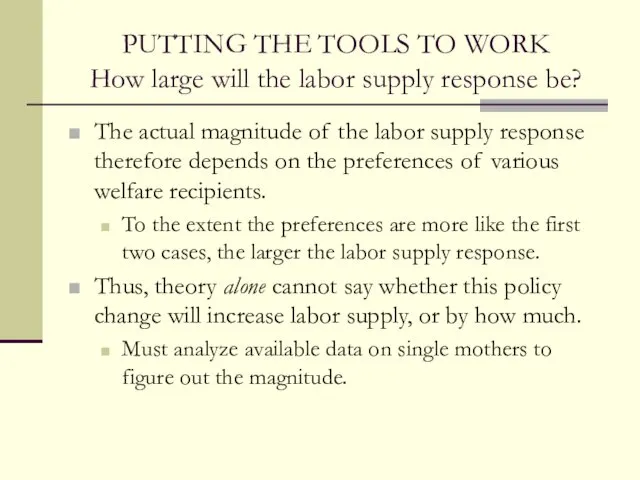

- 53. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be? The actual magnitude

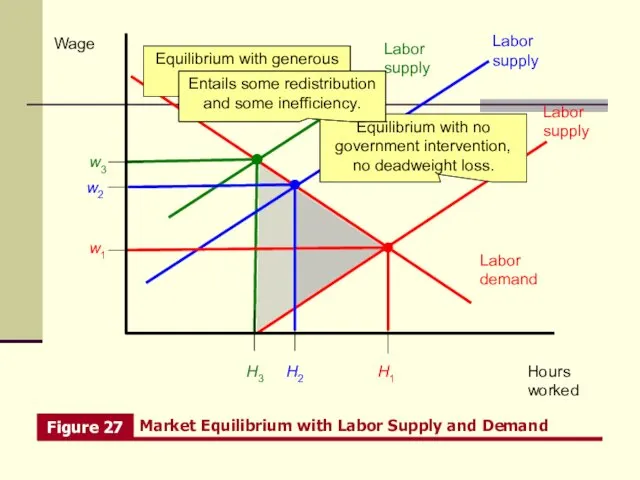

- 54. WELFARE IMPLICATIONS OF BENEFIT REDUCTIONS: TANF continued Efficiency and equity considerations in introducing or cutting TANF

- 55. Hours worked Wage H3 Labor demand w3 H2 w2 H1 w1 Labor supply Equilibrium with no

- 57. Скачать презентацию

Самоиндукция. Индуктивность

Самоиндукция. Индуктивность Частотно – регулируемый асинхронный электропривод

Частотно – регулируемый асинхронный электропривод Правотворчество и формирование закона

Правотворчество и формирование закона Деревянные балки в покрытиях и перекрытиях

Деревянные балки в покрытиях и перекрытиях Сердечнолегочная реанимация у детей

Сердечнолегочная реанимация у детей Конкурентные преимущества Raw Life Protein

Конкурентные преимущества Raw Life Protein Роль родного языка и речи в развитии ребенка

Роль родного языка и речи в развитии ребенка НУЗ Дорожная клиническая больница ОАО РЖД. Преимущества на рынке медицинских услуг

НУЗ Дорожная клиническая больница ОАО РЖД. Преимущества на рынке медицинских услуг Организация контроля на уроках информатики

Организация контроля на уроках информатики Approaches. Discussion

Approaches. Discussion Таблица умножения и деления на 2

Таблица умножения и деления на 2 Импульс тела. Закон сохранения импульса. Реактивное движение

Импульс тела. Закон сохранения импульса. Реактивное движение Право на образование

Право на образование Старая Уфа

Старая Уфа Доказательная медицина. Формулярная система. Фармакоэпидемиология

Доказательная медицина. Формулярная система. Фармакоэпидемиология Казань - спортивная столица

Казань - спортивная столица Социальное партнёрство с родителями, как условие развития творческих способностей обучающихся

Социальное партнёрство с родителями, как условие развития творческих способностей обучающихся  Разработка GIF-анимации через Photoshop

Разработка GIF-анимации через Photoshop Основні симптоми та синдроми при цукровому діабеті

Основні симптоми та синдроми при цукровому діабеті Неопределенные местоимения

Неопределенные местоимения Системы двух линейных уравнений с двумя переменными, как математические модели реальных ситуаций. 7 класс

Системы двух линейных уравнений с двумя переменными, как математические модели реальных ситуаций. 7 класс Колядки

Колядки Грыжи. Классификация грыж

Грыжи. Классификация грыж Методы исследования механической активности сердца

Методы исследования механической активности сердца Производство облицовочных работ

Производство облицовочных работ Ресторан BigMama

Ресторан BigMama Психические и поведенческие расстройства в результате употребления летучих растворителей (ингалянтов)

Психические и поведенческие расстройства в результате употребления летучих растворителей (ингалянтов) Презентация проекта Волшебная пуговица.

Презентация проекта Волшебная пуговица.