Содержание

- 2. Ideally, firms in an industry would like to capture most or all of the economic value

- 3. Michael Porter developed his Five Forces concept from basic ideas in the field of industrial economics.

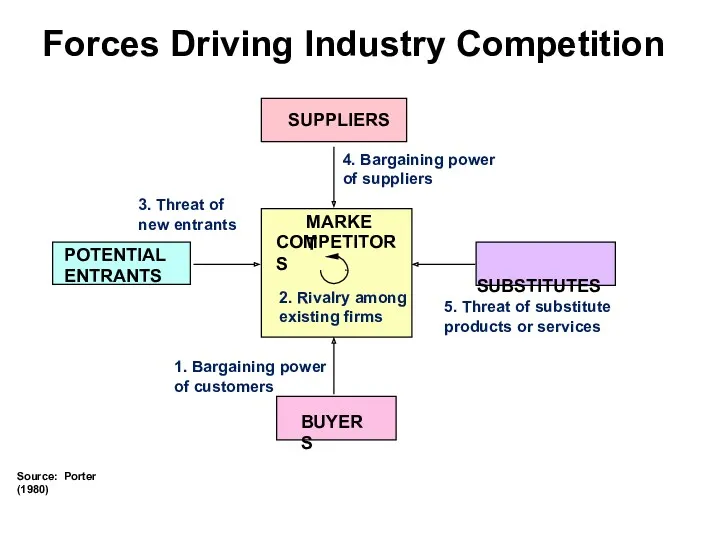

- 4. BUYERS 3. Threat of new entrants MARKET COMPETITORS 1. Bargaining power of customers SUPPLIERS SUBSTITUTES 2.

- 5. The previous lecture illustrated the impact of two of Porter’s “Five Forces of Competition”: Bargaining Power

- 6. Let’s begin with the two forces implicit in the examples from last time. According to Porter

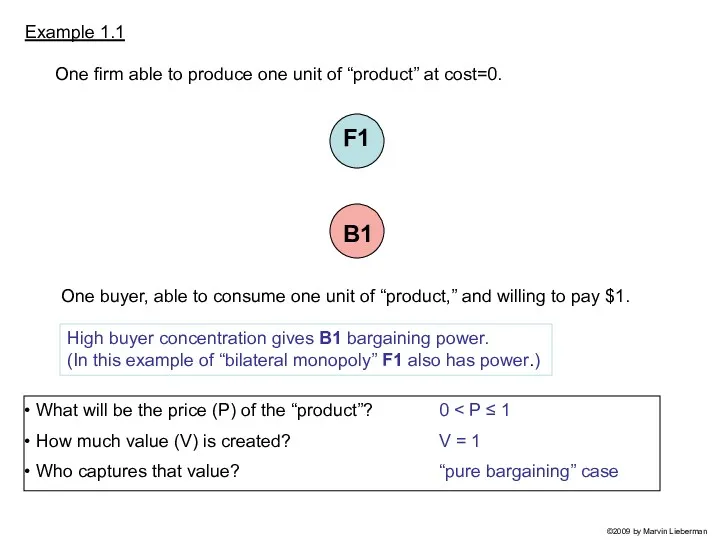

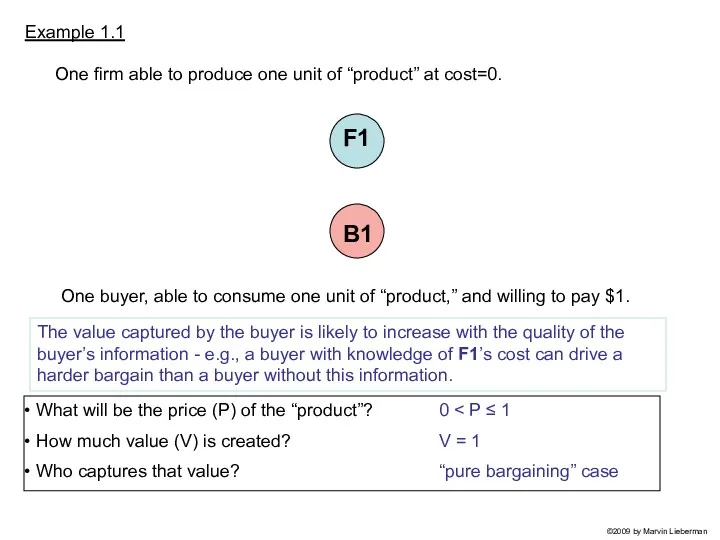

- 7. What will be the price (P) of the “product”? How much value (V) is created? Who

- 8. What will be the price (P) of the “product”? How much value (V) is created? Who

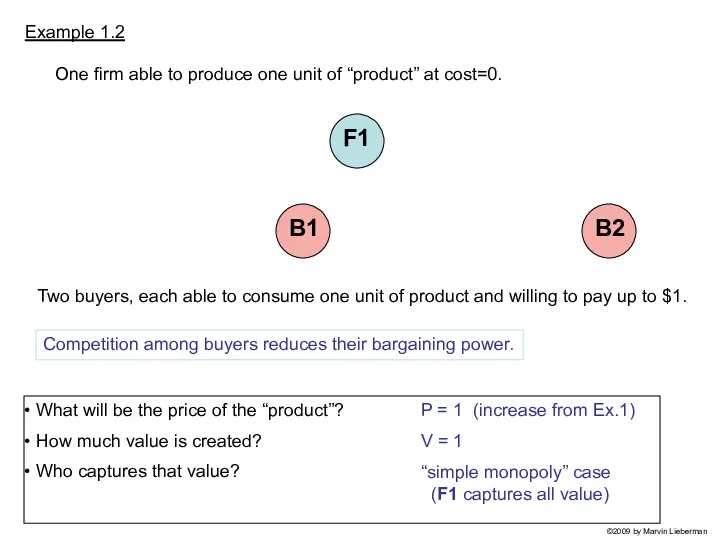

- 9. What will be the price of the “product”? How much value is created? Who captures that

- 10. Buyer power greater when: Buyers are more concentrated Buyers are better informed Implications ©2009 by Marvin

- 11. We also saw that an increase in producer rivalry makes the industry less attractive. Consider examples

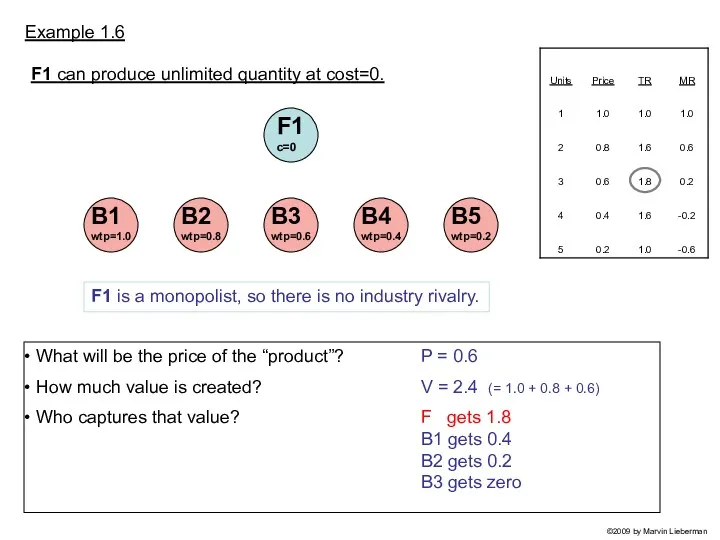

- 12. Example 1.6 What will be the price of the “product”? How much value is created? Who

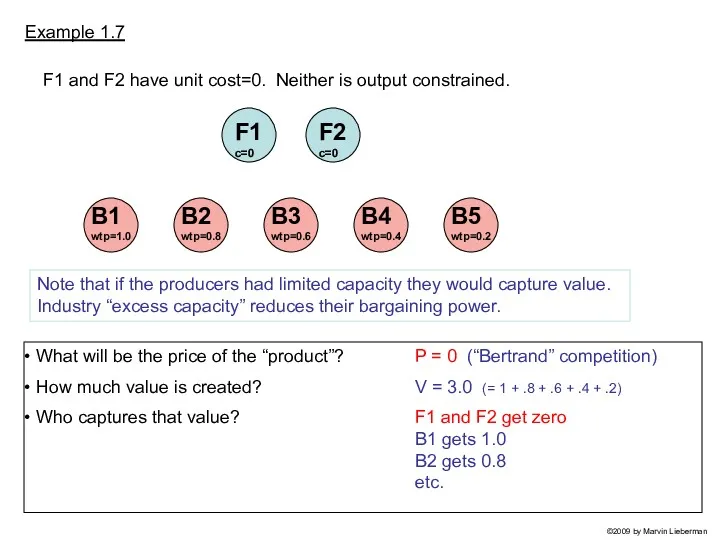

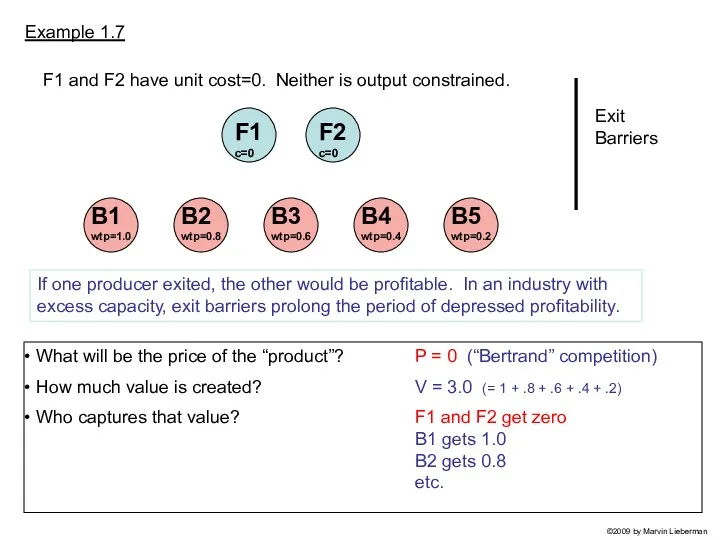

- 13. Example 1.7 What will be the price of the “product”? How much value is created? Who

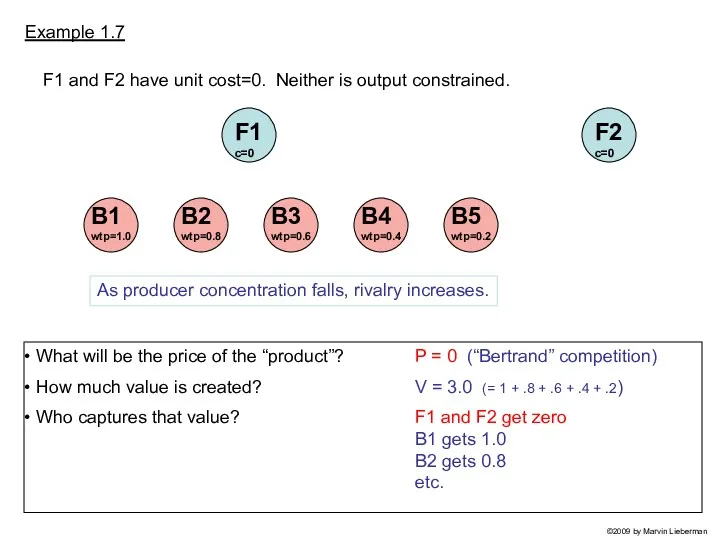

- 14. Example 1.7 What will be the price of the “product”? How much value is created? Who

- 15. Example 1.7 What will be the price of the “product”? How much value is created? Who

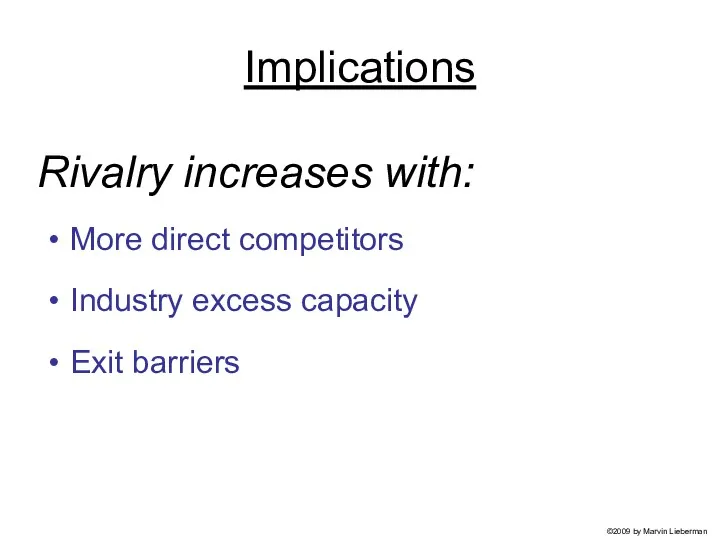

- 16. Implications More direct competitors Industry excess capacity Exit barriers Rivalry increases with: ©2009 by Marvin Lieberman

- 17. Now let’s consider the threat of entry. ©2009 by Marvin Lieberman

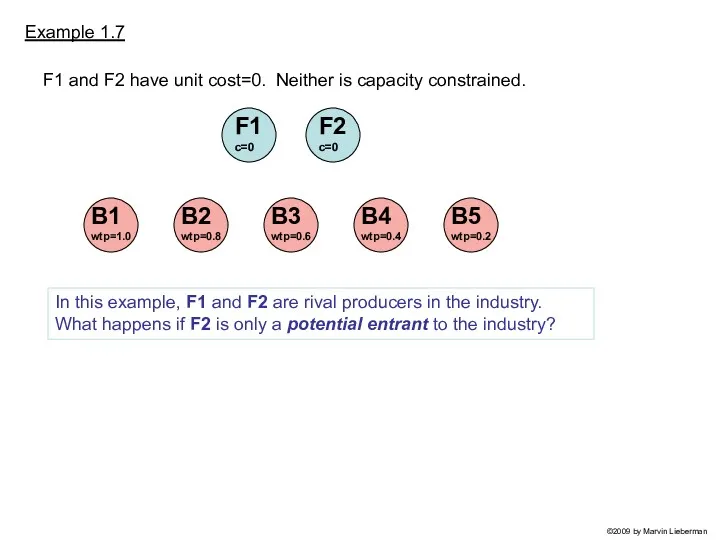

- 18. Example 1.7 F1 c=0 F2 c=0 F1 and F2 have unit cost=0. Neither is capacity constrained.

- 19. Example 1.7a F1 c=0 F1 and F2 have unit cost=0. Neither is capacity constrained. If F2

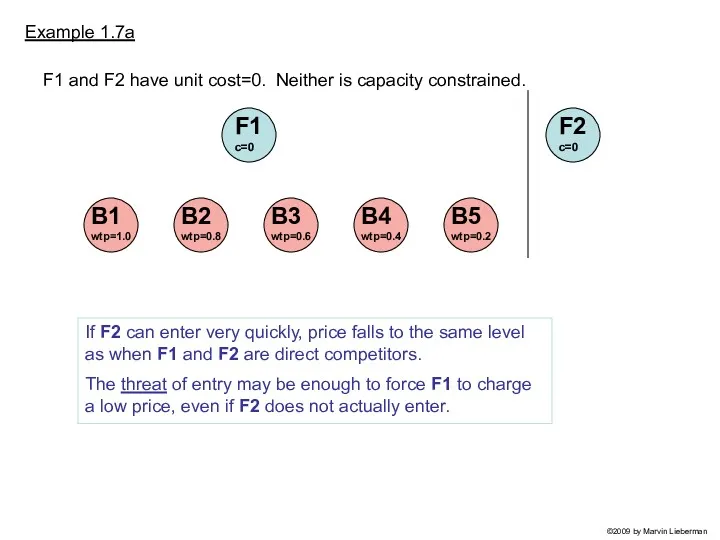

- 20. Example 1.7b F1 c=0 F1 and F2 have unit cost=0. Neither is capacity constrained. If entry

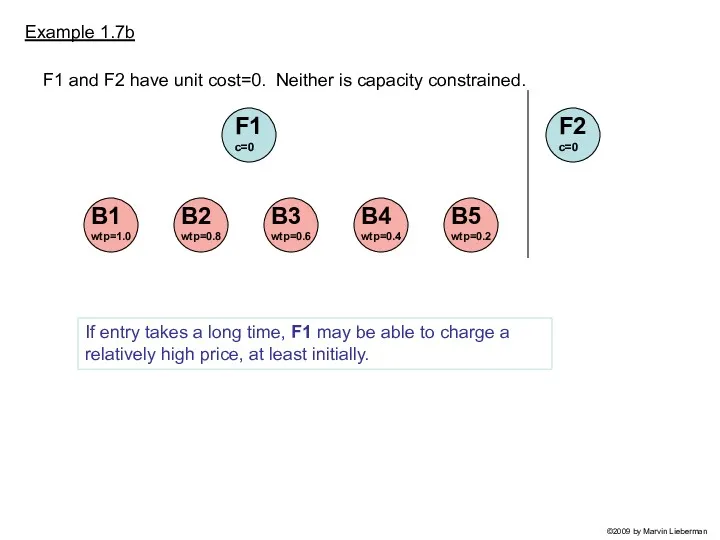

- 21. Example 1.7c F1 c=0 F2 has higher cost. Neither firm is capacity constrained. If entry involves

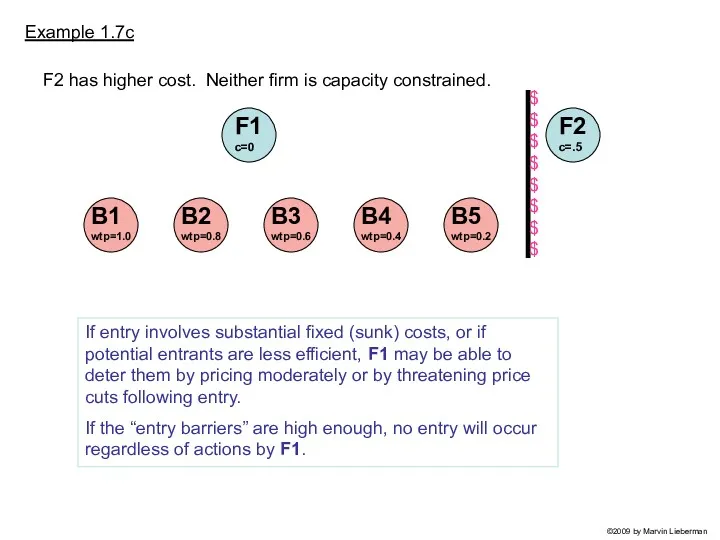

- 22. Potential Entrants Almost like rival producers (when entry is fast) Impeded by “entry barriers” (costs of

- 23. Now let’s consider the impact of “supplier power.” We will add supplier(s) as an additional level

- 24. New Example. F1 and F2 have cost=0 and each can produce one unit. B1, B2 and

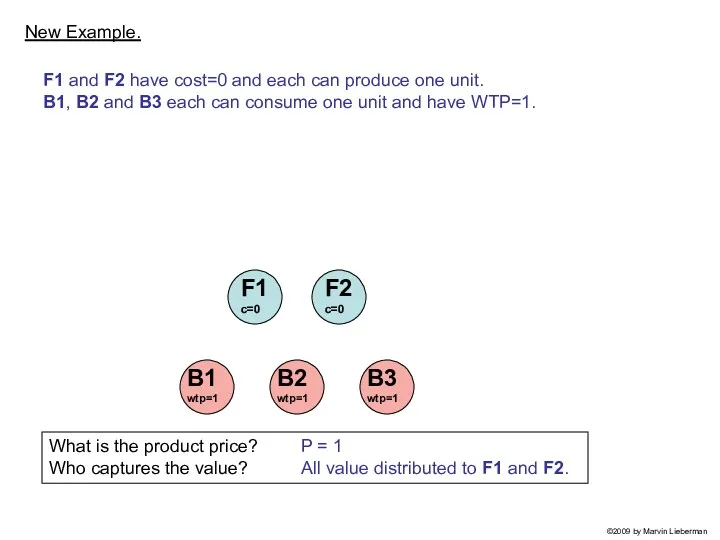

- 25. What is the input price (P*)? What is the product price? Who captures the value? P*=

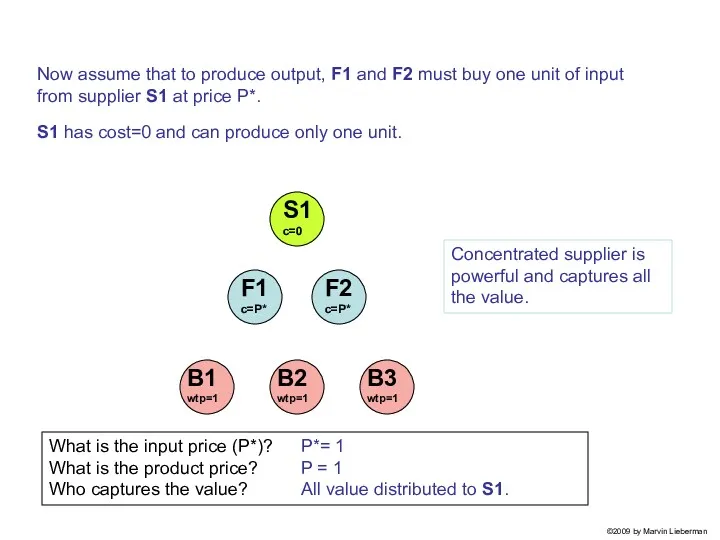

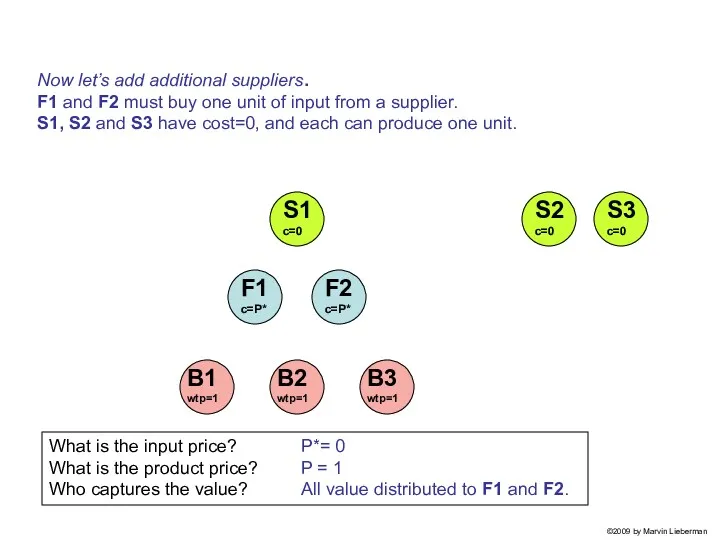

- 26. What is the input price? What is the product price? Who captures the value? P*= 0

- 27. Implications Suppliers can siphon value from producers Power increases with supplier concentration Analysis similar to buyer

- 28. Application One example of a supplier with market power is Microsoft, whose “Windows” software has long

- 29. As we will see, substitutes act to reduce the economic value that firms in the focal

- 30. As we will see, substitutes act to reduce the economic value that firms in the focal

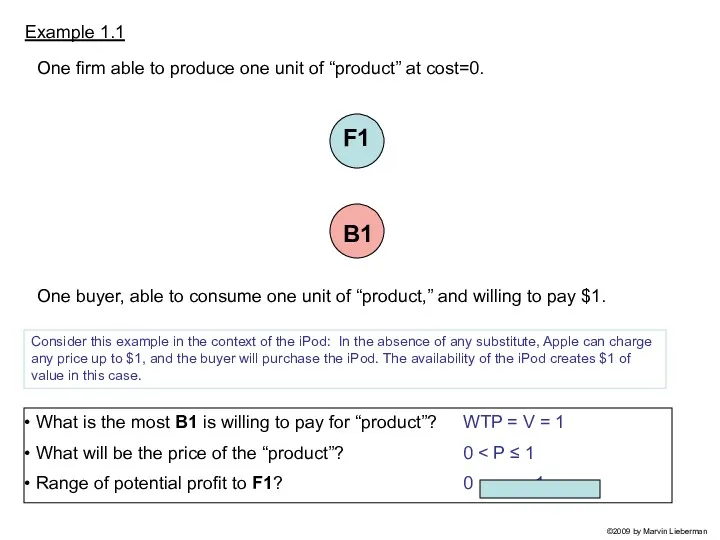

- 31. One buyer, able to consume one unit of “product,” and willing to pay $1. B1 F1

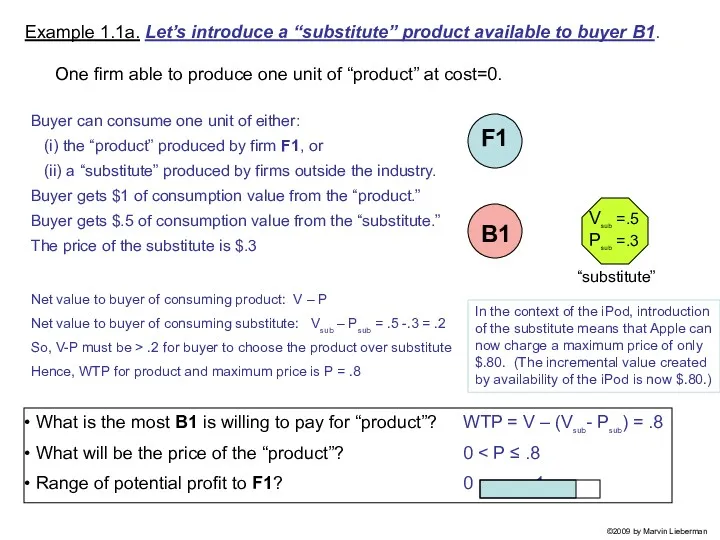

- 32. One firm able to produce one unit of “product” at cost=0. Example 1.1a. Let’s introduce a

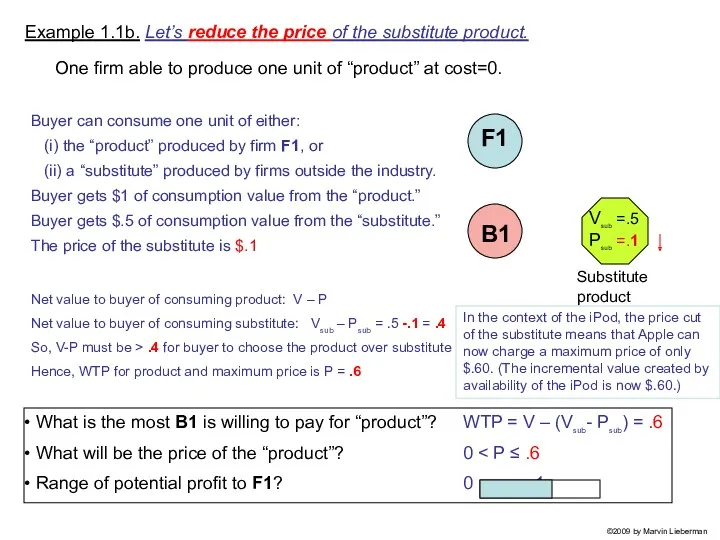

- 33. One firm able to produce one unit of “product” at cost=0. Example 1.1b. Let’s reduce the

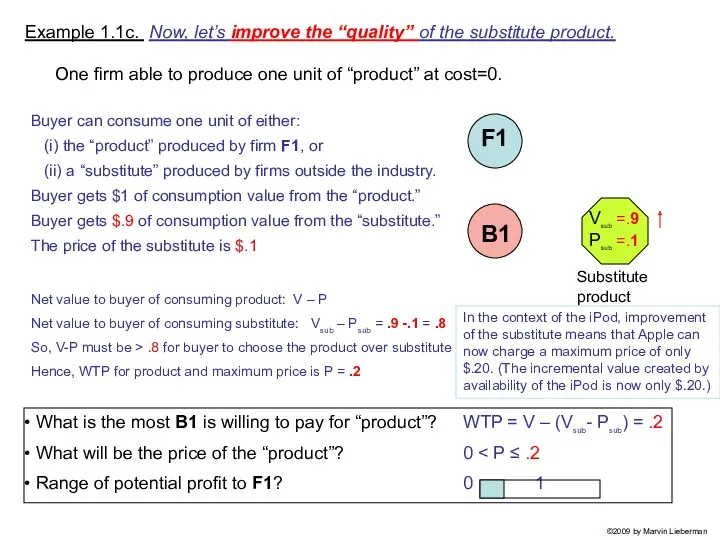

- 34. One firm able to produce one unit of “product” at cost=0. Example 1.1c. Now, let’s improve

- 35. Competition from Substitutes Reduces buyers’ WTP for the industry’s product. Strengthens bargaining position of single buyer.

- 36. Impact of Complements Sometimes called the “sixth industry force.” Can be viewed as opposite of substitutes.

- 37. Conclusions Bargaining Power of Buyers Rivalry Between Established Competitors Threat of Entry Bargaining Power of Suppliers

- 38. Conclusions The examples here have been relatively simple, but they illustrate the basic operation of the

- 40. Скачать презентацию

Подборка презентаций к урокам экономики ( вторая часть )

Подборка презентаций к урокам экономики ( вторая часть ) Зовнішньоекономічна діяльність та її роль у розвитку національної економіки

Зовнішньоекономічна діяльність та її роль у розвитку національної економіки Soft Computingga kirish

Soft Computingga kirish Функционально-стоимостной анализ

Функционально-стоимостной анализ Elastyczność popytu i podaży

Elastyczność popytu i podaży Фирмы в экономике

Фирмы в экономике Субъект международного права : Республика Индия

Субъект международного права : Республика Индия Бизнес – план создания спорт - бара

Бизнес – план создания спорт - бара Равновесие, эффективность и государство

Равновесие, эффективность и государство Организация производства на предприятии

Организация производства на предприятии Международная интеграция

Международная интеграция Региональное управление (цели, задачи, функции)

Региональное управление (цели, задачи, функции) Основные фонды предприятия

Основные фонды предприятия Қазақ қауымның дүниетанымы : қалыптасуы мен өзгеріске бейімделу

Қазақ қауымның дүниетанымы : қалыптасуы мен өзгеріске бейімделу Анализ использования трудовых ресурсов предприятия

Анализ использования трудовых ресурсов предприятия Рыночная экономика 8 класс

Рыночная экономика 8 класс Об’єкт, предмет і завдання дисципліни “Економіка праці й соціально-трудові відносини”

Об’єкт, предмет і завдання дисципліни “Економіка праці й соціально-трудові відносини” Қр үкіметінің тұрақты экономикалық өсуді және жұмыспен қамтуды қамтамасыз етуге арналған дағдарысқа қарсы

Қр үкіметінің тұрақты экономикалық өсуді және жұмыспен қамтуды қамтамасыз етуге арналған дағдарысқа қарсы Матричные методы стратегического анализа

Матричные методы стратегического анализа Негізгі капитал

Негізгі капитал Инфляция и семейная экономика

Инфляция и семейная экономика Роль экономики в жизни общества

Роль экономики в жизни общества Показатели, которые необходимо прогнозировать в сфере потребительский рынок

Показатели, которые необходимо прогнозировать в сфере потребительский рынок Инфляция. Определение понятия инфляция

Инфляция. Определение понятия инфляция О мерах поддержки, предоставляемых но Фонд развития моногородов

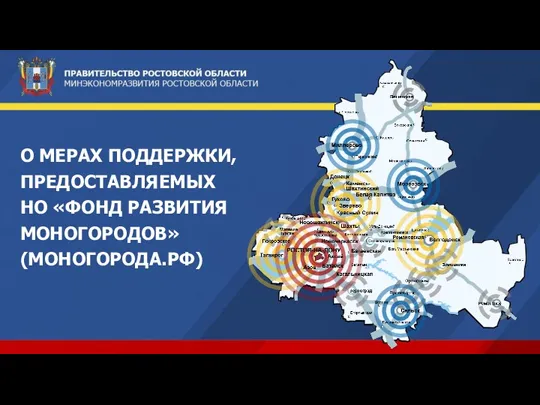

О мерах поддержки, предоставляемых но Фонд развития моногородов механизмы рынка. Тема 3-4

механизмы рынка. Тема 3-4 Случаи несостоятельности рынка. Внешние эффекты

Случаи несостоятельности рынка. Внешние эффекты Традиционный старый институционализм

Традиционный старый институционализм