Содержание

- 2. Course of lectures «Contemporary Physics: Part1» Lecture №3 Dynamics of mas point and rigid body. Newton’s

- 3. Previously we described motion in terms of position, velocity, and acceleration without considering what might cause

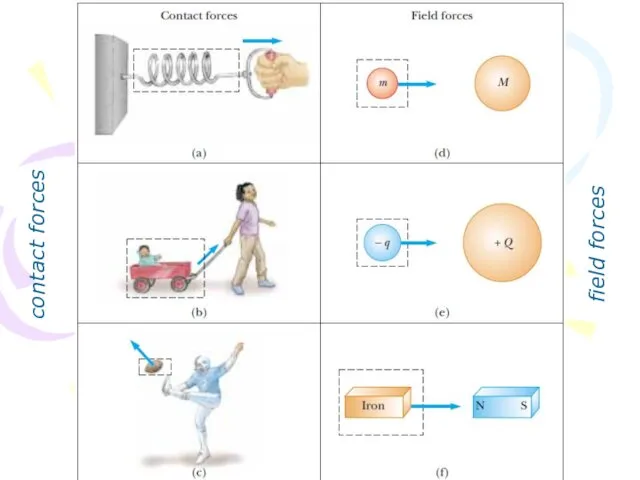

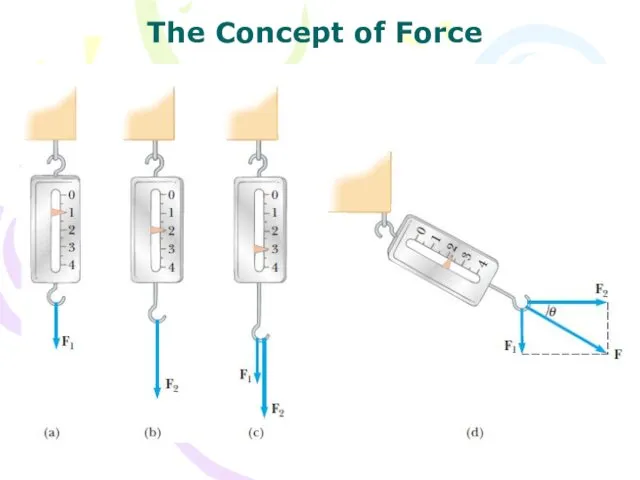

- 4. The Concept of Force contact forces field forces

- 5. The Concept of Force The only known fundamental forces in nature are all field forces: gravitational

- 6. The Concept of Force

- 7. If an object does not interact with other objects, it is possible to identify a reference

- 8. Such a reference frame is called an inertial frame of reference. Any reference frame that moves

- 9. When no force acts on an object, the acceleration of the object is zero. In the

- 10. Mass Mass is that property of an object that specifies how much resistance an object exhibits

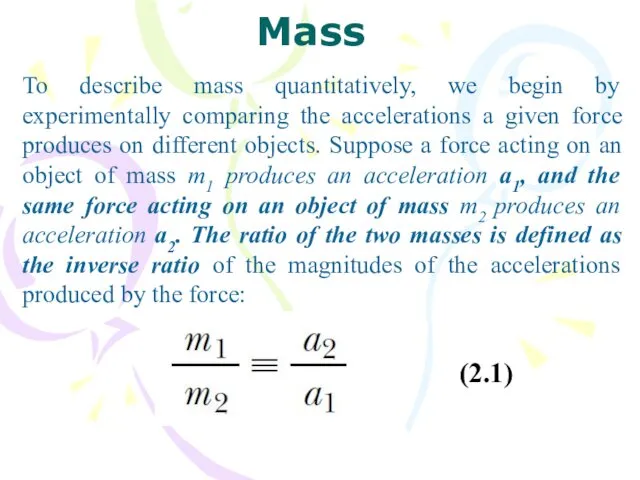

- 11. To describe mass quantitatively, we begin by experimentally comparing the accelerations a given force produces on

- 12. Mass is an inherent property of an object and is independent of the object’s surroundings and

- 13. Mass should not be confused with weight. Mass and weight are two different quantities. The weight

- 14. Newton’s first law explains what happens to an object when no forces act on it. It

- 15. Imagine performing an experiment in which you push a block of ice across a frictionless horizontal

- 16. The acceleration of an object also depends on its mass, as stated in the preceding section.

- 17. According to this observation, we conclude that the magnitude of the acceleration of an object is

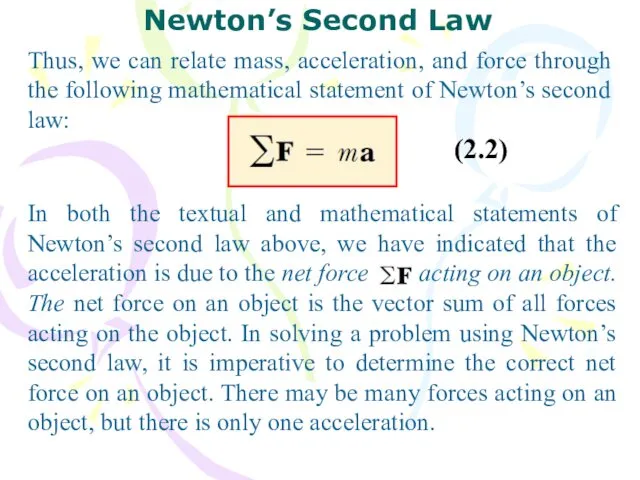

- 18. Thus, we can relate mass, acceleration, and force through the following mathematical statement of Newton’s second

- 19. The SI unit of force is the newton, which is defined as the force that, when

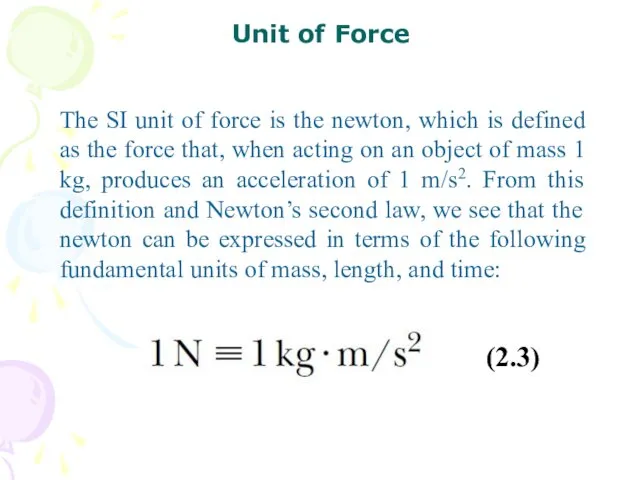

- 20. (2.4) The Gravitational Force and Weight

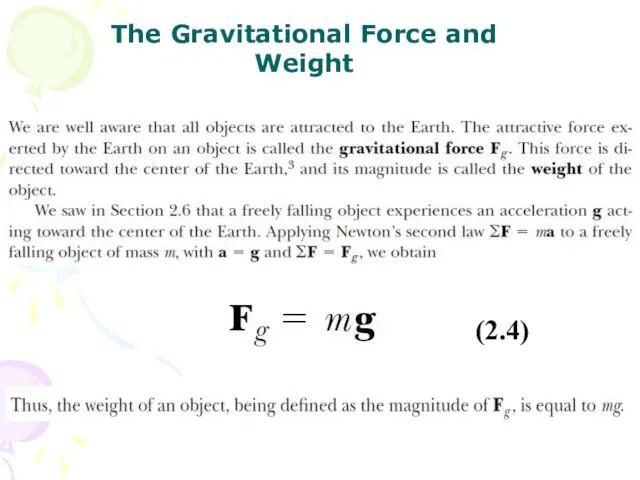

- 21. The Gravitational Force and Weight

- 22. If you press against a corner of this textbook with your fingertip, the book pushes back

- 23. Forces always occur in pairs, or that a single isolated force cannot exist. The force that

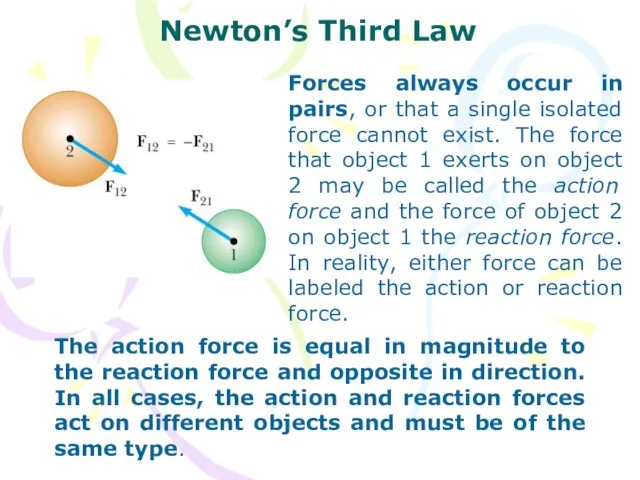

- 24. Newton’s Third Law

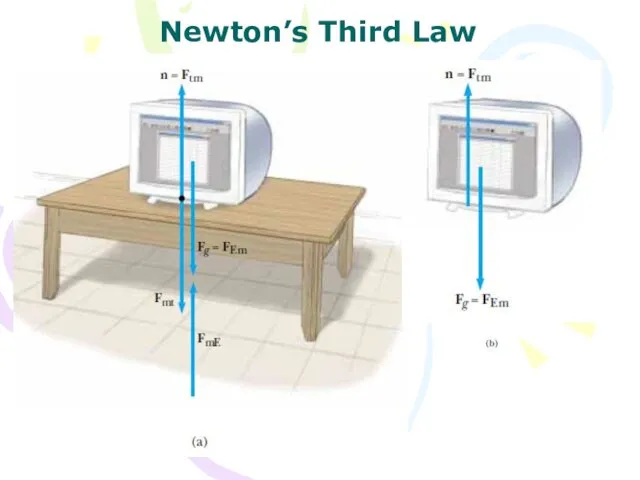

- 25. Newton’s Third Law When we apply Newton’s laws to an object, we are interested only in

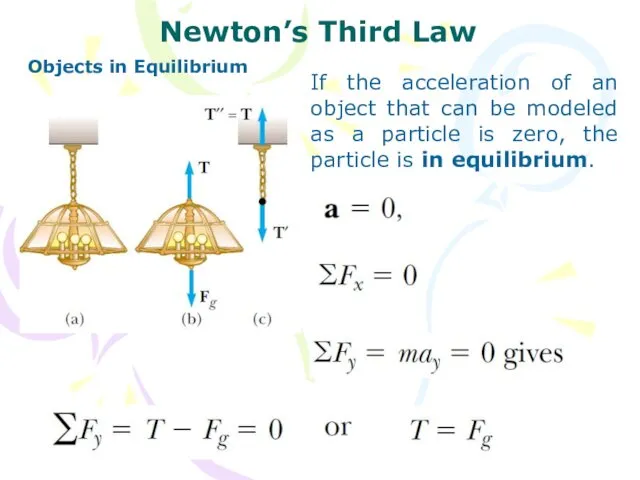

- 26. Newton’s Third Law Objects in Equilibrium If the acceleration of an object that can be modeled

- 27. Newton’s Third Law Objects Experiencing a Net Force constant

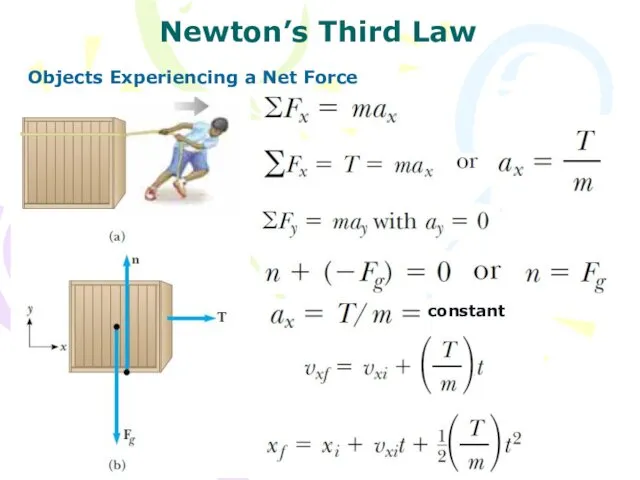

- 28. Actions of bodies to each other, making the accelerations, called forces. All forces can be divided

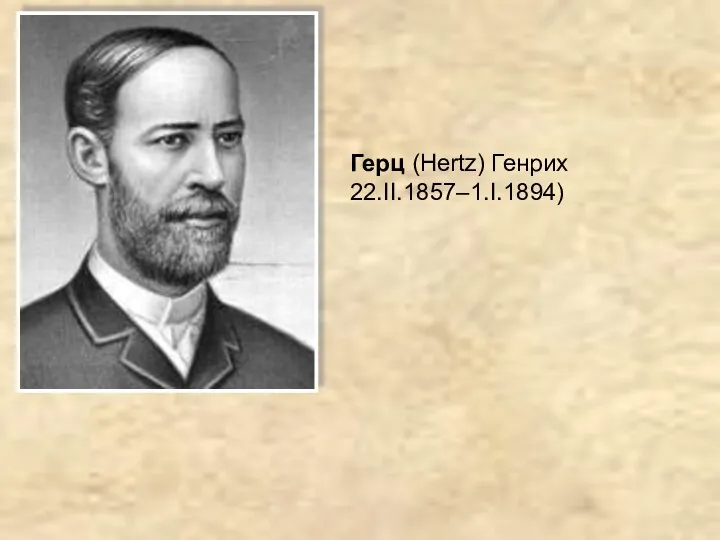

- 29. Except elastic forces at the direct contact can appear forces of another type so called forces

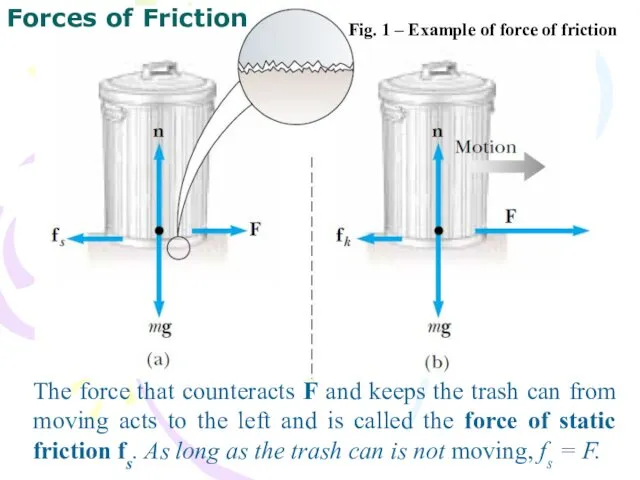

- 30. The force that counteracts F and keeps the trash can from moving acts to the left

- 31. The magnitude of the force of static friction between any two surfaces in contact can have

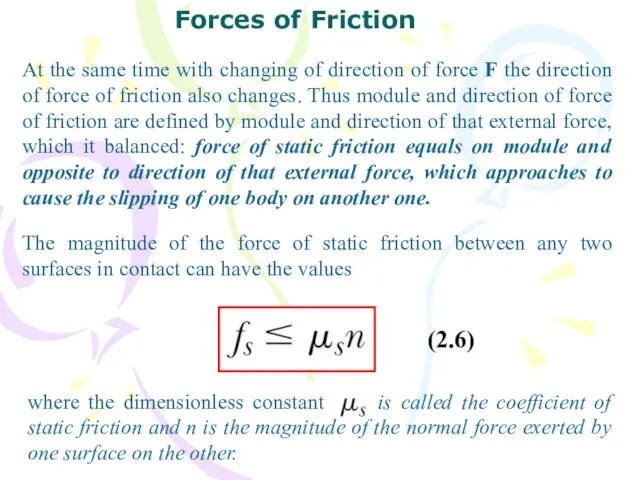

- 32. We call the friction force for an object in motion the force of kinetic friction fk

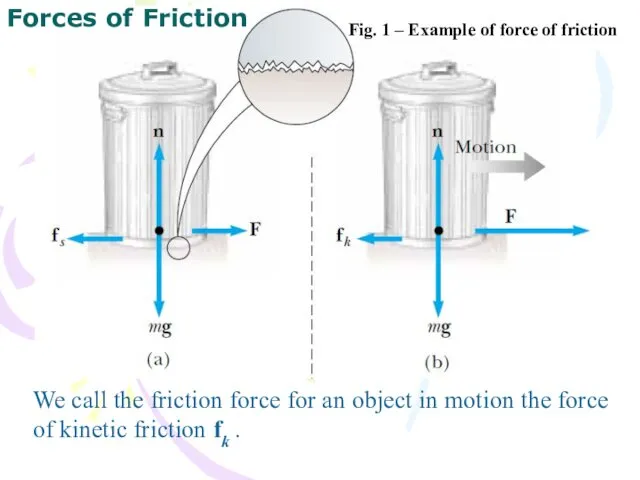

- 33. The magnitude of the force of kinetic friction acting between two surfaces is where is the

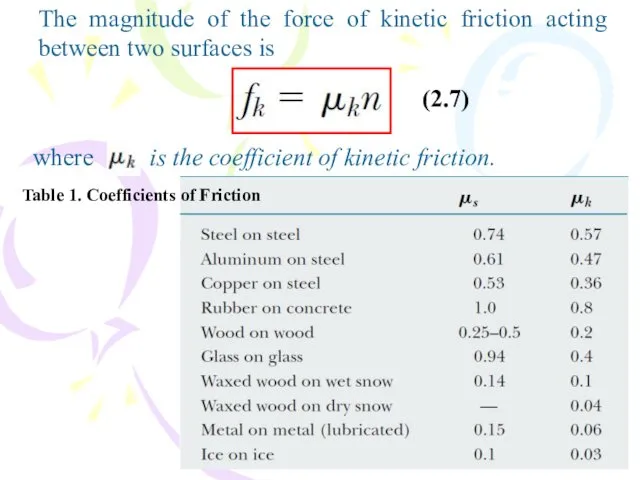

- 34. A particle moving with uniform speed v in a circular path of radius r experiences an

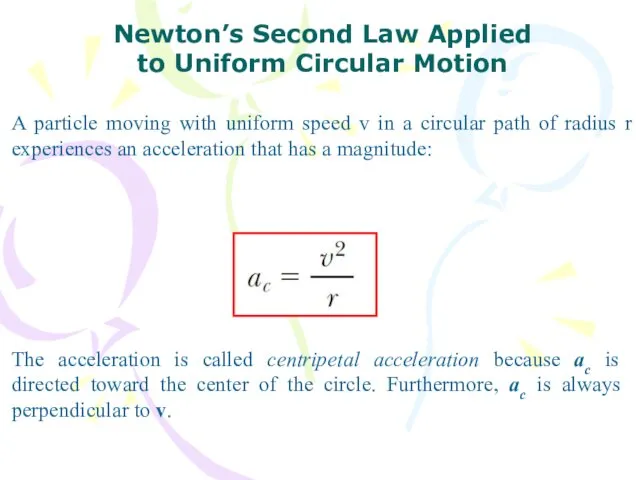

- 35. Figure 2. Overhead view of a ball moving in a circular path in a horizontal plane.

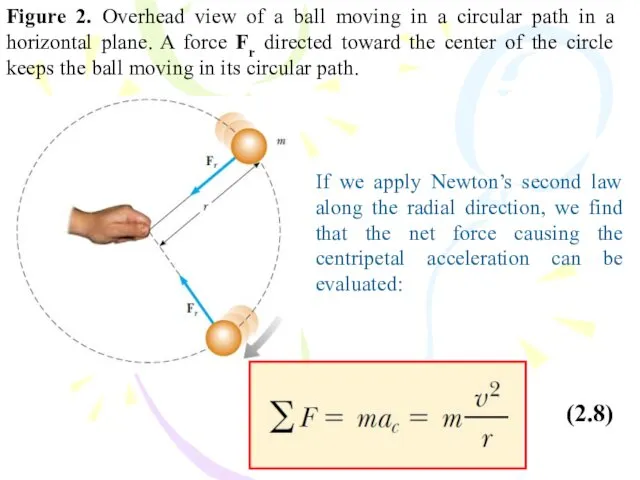

- 36. If a particle moves with varying speed in a circular path, there is, in addition to

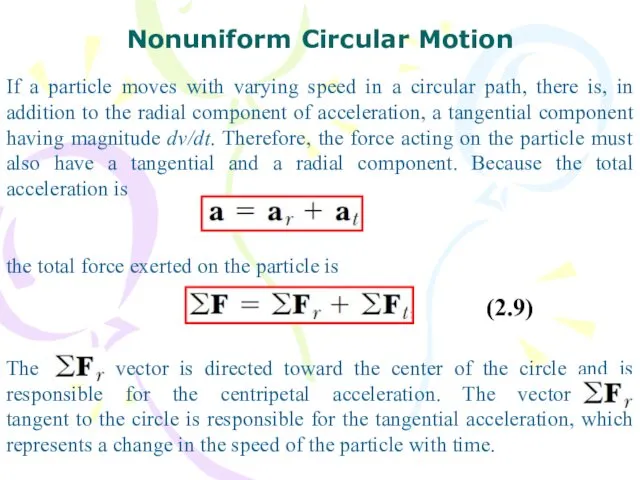

- 37. Nonuniform Circular Motion A small sphere of mass m is attached to the end of a

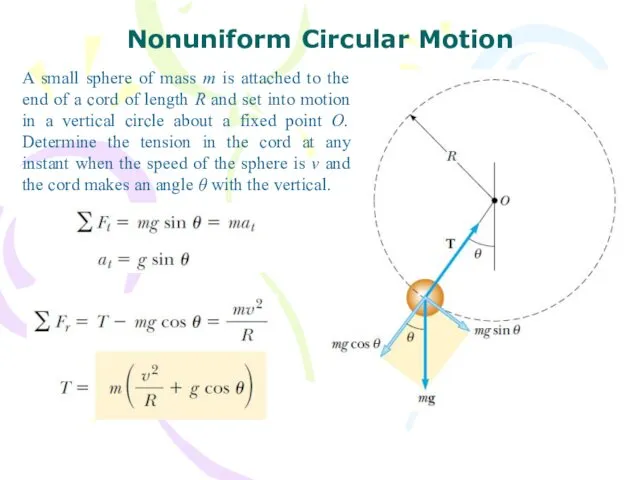

- 38. Motion in Accelerated Frames Figure 3. (a) A car approaching a curved exit ramp. What causes

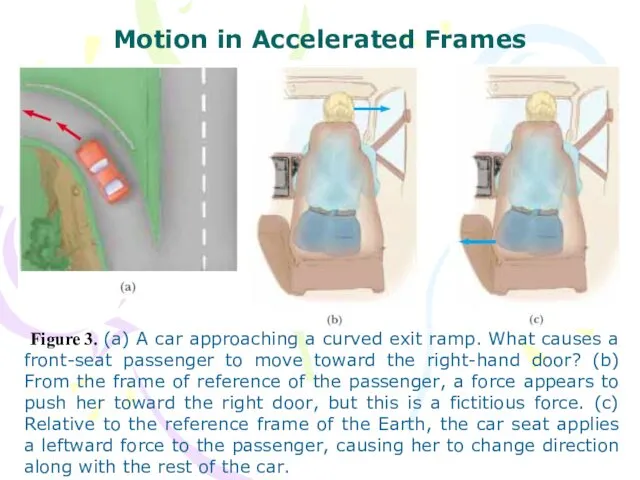

- 39. Motion in Accelerated Frames Figure 4.

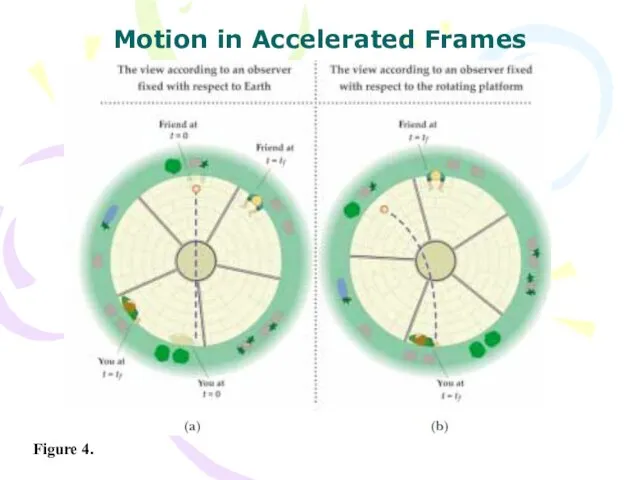

- 41. Скачать презентацию

Перший омнібус Д.Шилібіра

Перший омнібус Д.Шилібіра Система полного привода 4Motion Volkswagen. Трансмиссия

Система полного привода 4Motion Volkswagen. Трансмиссия Работа. Энергия. Механика

Работа. Энергия. Механика Физические основы механики

Физические основы механики Тепловые двигатели

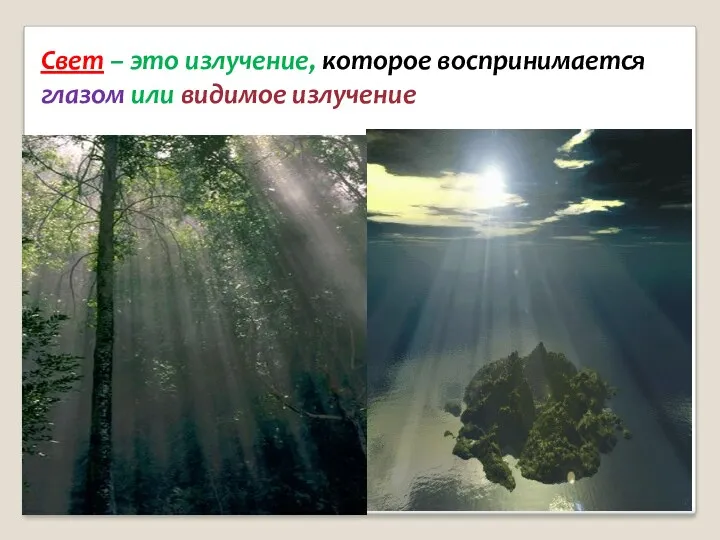

Тепловые двигатели Источники света,Прямолинейное распространение света

Источники света,Прямолинейное распространение света Зубчатая передача

Зубчатая передача Сила трения. (7 класс)

Сила трения. (7 класс) Gas Dynamics (Introduction to Compressible Flow) Lecture 6a and 6b

Gas Dynamics (Introduction to Compressible Flow) Lecture 6a and 6b Основы трибофатики (трибофатика)

Основы трибофатики (трибофатика) Нанотехнологии и их применение

Нанотехнологии и их применение Проблемное обучение в преподавании физики

Проблемное обучение в преподавании физики Энтропия. Тепловые двигатели. (Лекция 10)

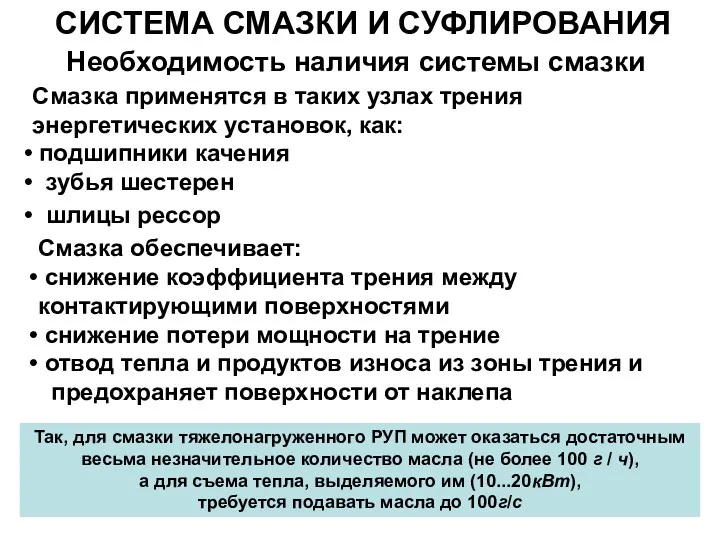

Энтропия. Тепловые двигатели. (Лекция 10) Система смазки и суфлирования

Система смазки и суфлирования Презентация. Обучение детей с учётом психофизиологии.

Презентация. Обучение детей с учётом психофизиологии. квантовая физика

квантовая физика Что изучает физика? Некоторые физические термины

Что изучает физика? Некоторые физические термины Урок физики в 8 классе Энергия топлива. Удельная теплота сгорания топлива

Урок физики в 8 классе Энергия топлива. Удельная теплота сгорания топлива методическая разработка урока

методическая разработка урока Internal combustion engine

Internal combustion engine презентация открытого урока: Строение атома

презентация открытого урока: Строение атома Физико-химические методы анализа

Физико-химические методы анализа Элементы машиноведения. Составные части машин

Элементы машиноведения. Составные части машин Проектирование зоны ТО-1 грузовых автомобилей с выделением шиномонтажного участка, технологический процесс ремонта колес

Проектирование зоны ТО-1 грузовых автомобилей с выделением шиномонтажного участка, технологический процесс ремонта колес Какие факторы влияют на испарение различных жидкостей

Какие факторы влияют на испарение различных жидкостей Радиационные методы контроля

Радиационные методы контроля Индикаторные и эффективные показатели ДВС. Тема 8

Индикаторные и эффективные показатели ДВС. Тема 8 игра инерция

игра инерция