Содержание

- 2. Solution methods Focus on finite volume method. Background of finite volume method. Discretization example. General solution

- 3. Overview of numerical methods Many CFD techniques exist. The most common in commercially available CFD programs

- 4. Finite difference method (FDM) Historically, the oldest of the three. Techniques published as early as 1910

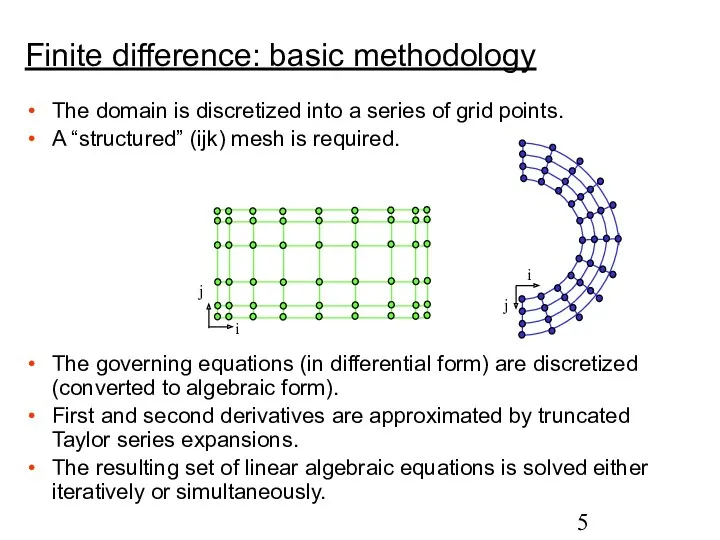

- 5. The domain is discretized into a series of grid points. A “structured” (ijk) mesh is required.

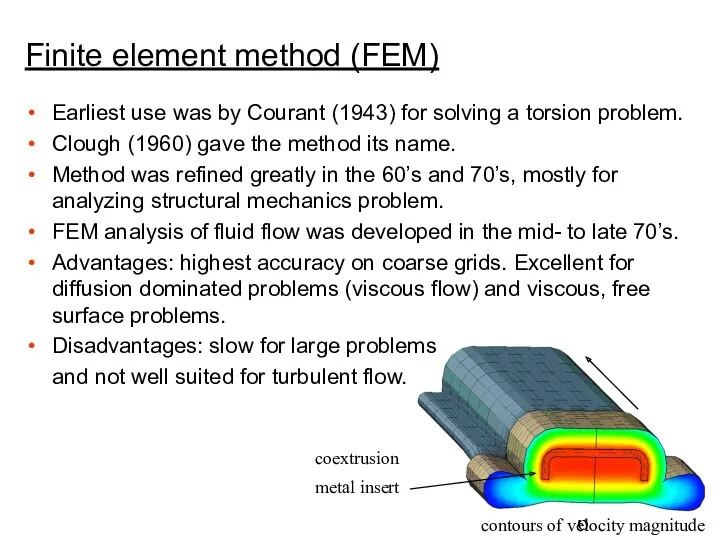

- 6. Earliest use was by Courant (1943) for solving a torsion problem. Clough (1960) gave the method

- 7. First well-documented use was by Evans and Harlow (1957) at Los Alamos and Gentry, Martin and

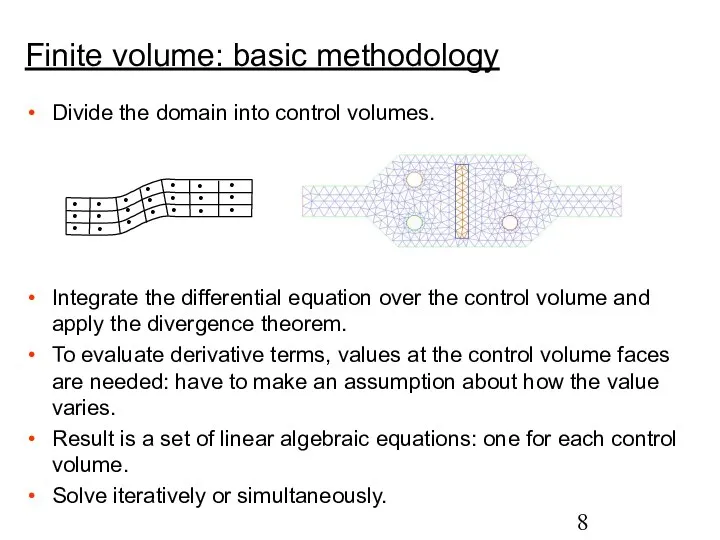

- 8. Divide the domain into control volumes. Integrate the differential equation over the control volume and apply

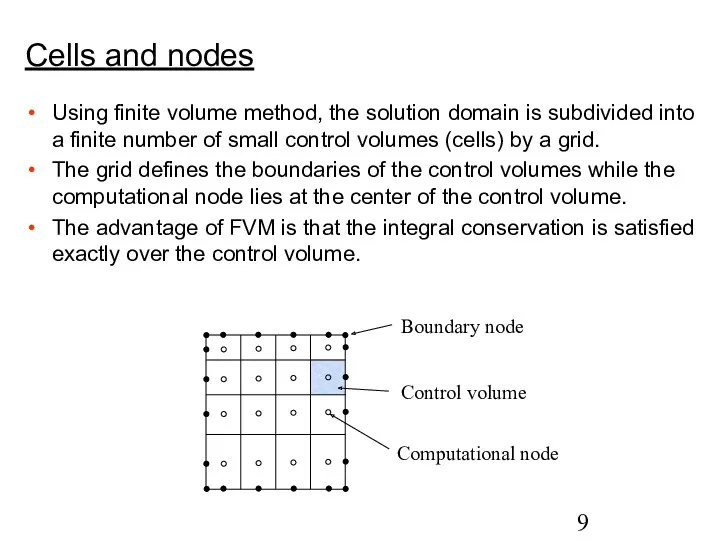

- 9. Cells and nodes Using finite volume method, the solution domain is subdivided into a finite number

- 10. The net flux through the control volume boundary is the sum of integrals over the four

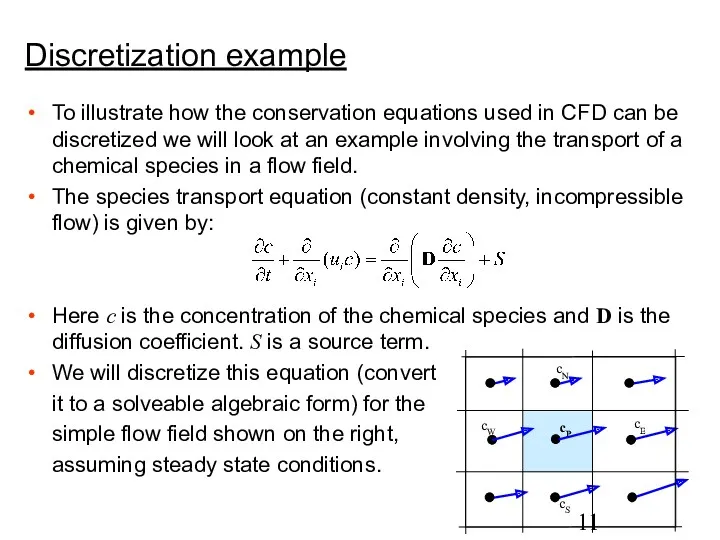

- 11. Discretization example To illustrate how the conservation equations used in CFD can be discretized we will

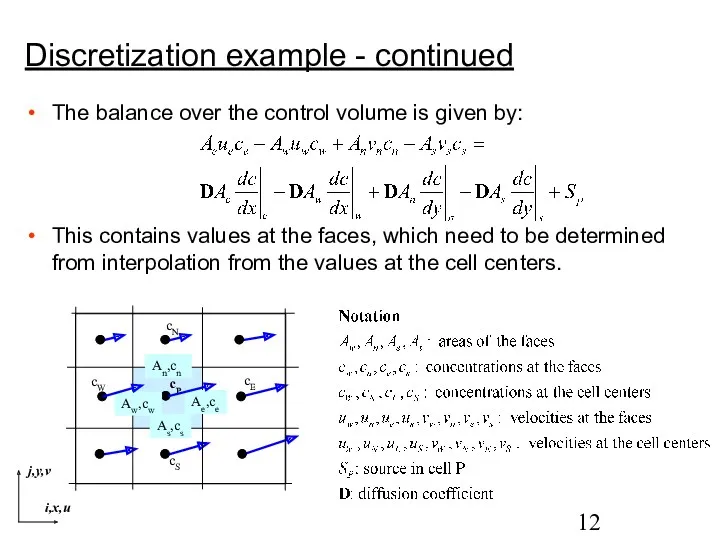

- 12. Discretization example - continued The balance over the control volume is given by: This contains values

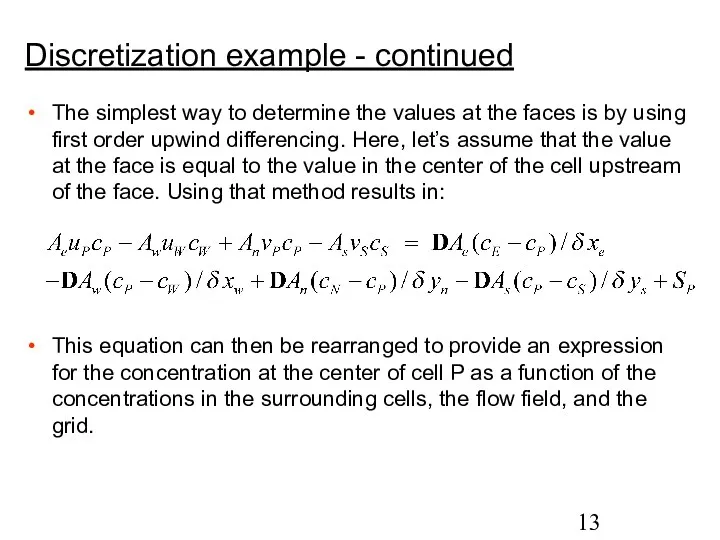

- 13. Discretization example - continued The simplest way to determine the values at the faces is by

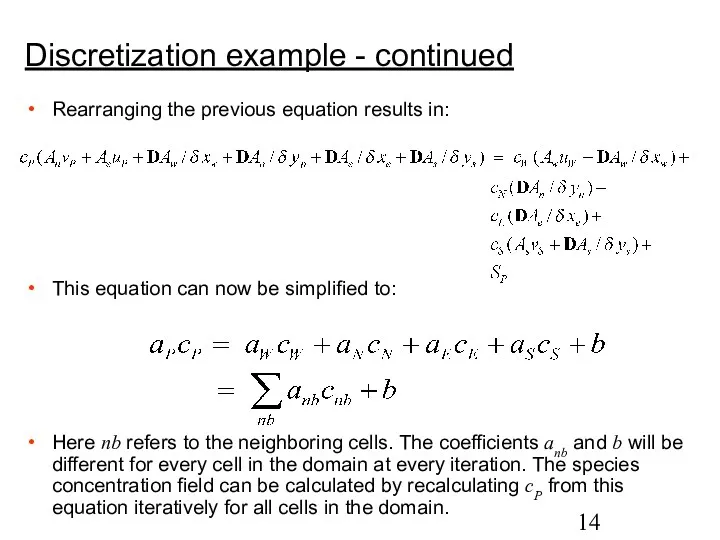

- 14. Discretization example - continued Rearranging the previous equation results in: This equation can now be simplified

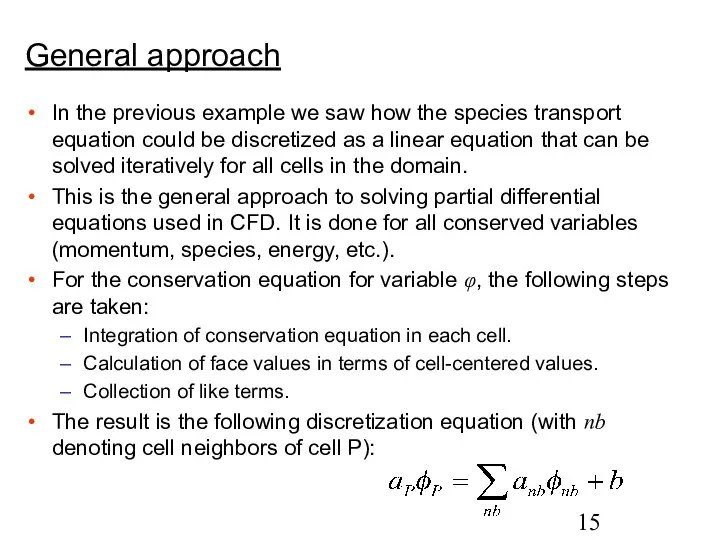

- 15. General approach In the previous example we saw how the species transport equation could be discretized

- 16. General approach - relaxation At each iteration, at each cell, a new value for variable φ

- 17. Underrelaxation recommendation Underrelaxation factors are there to suppress oscillations in the flow solution that result from

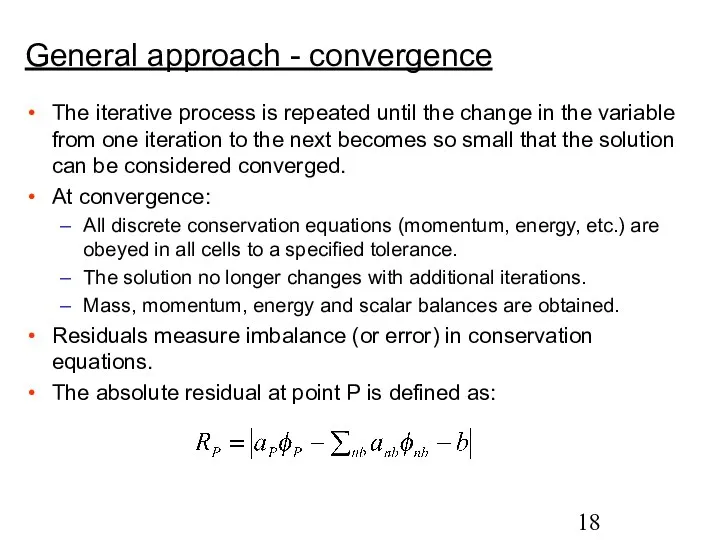

- 18. The iterative process is repeated until the change in the variable from one iteration to the

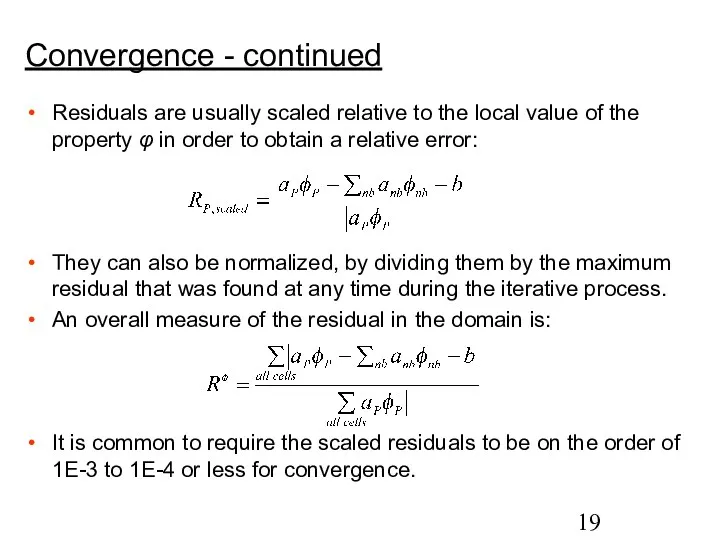

- 19. Residuals are usually scaled relative to the local value of the property φ in order to

- 20. Notes on convergence Always ensure proper convergence before using a solution: unconverged solutions can be misleading!!

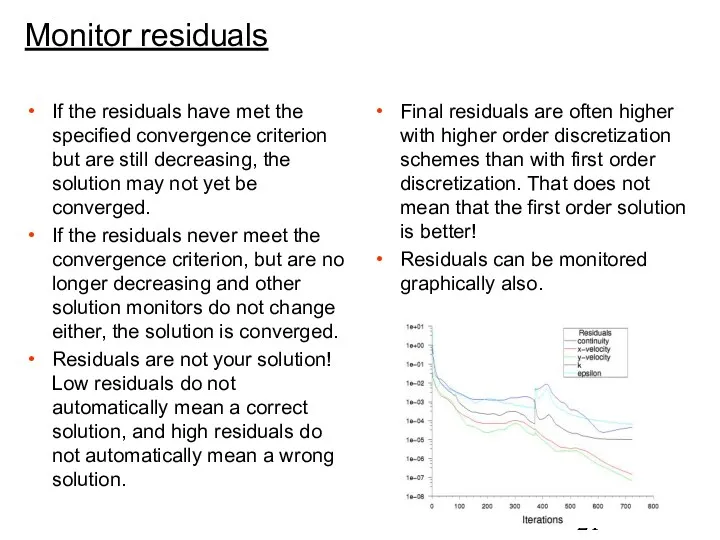

- 21. Monitor residuals If the residuals have met the specified convergence criterion but are still decreasing, the

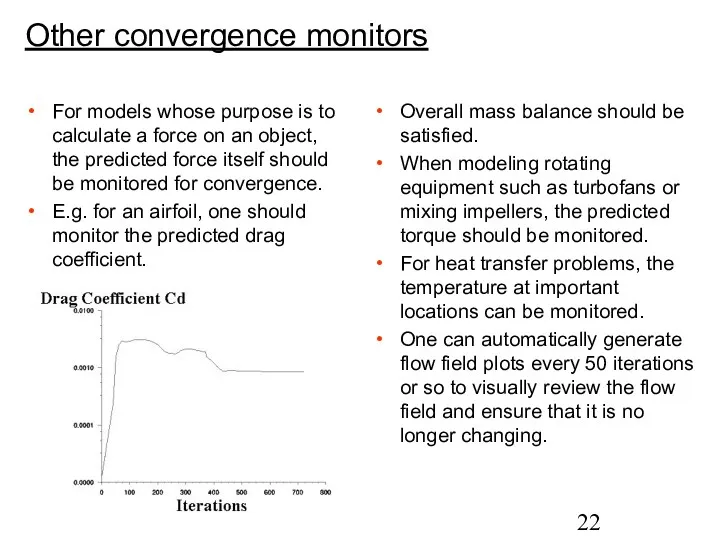

- 22. Other convergence monitors For models whose purpose is to calculate a force on an object, the

- 23. Face values of φ and ∂φ/∂x are found by making assumptions about variation of φ between

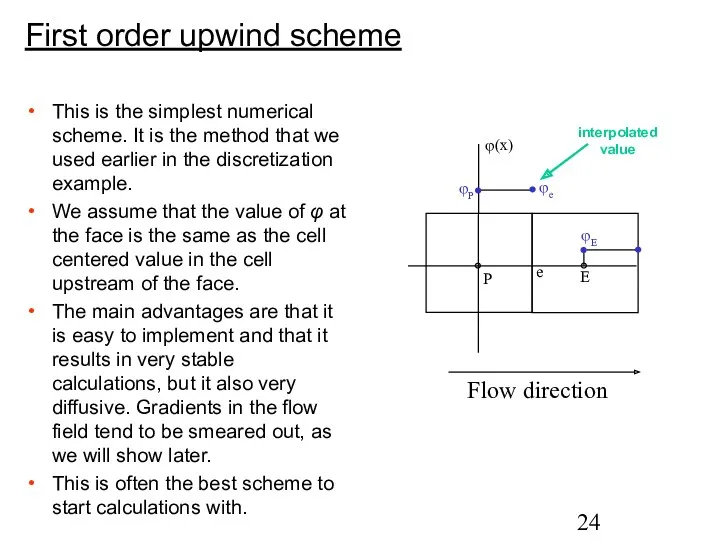

- 24. First order upwind scheme This is the simplest numerical scheme. It is the method that we

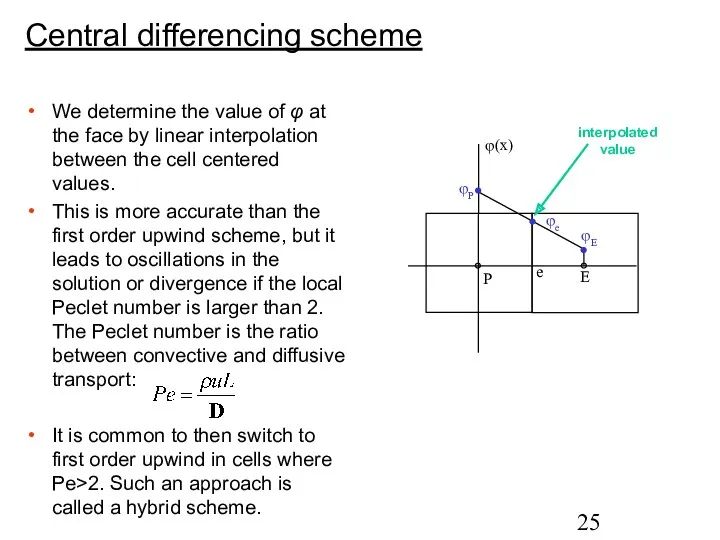

- 25. Central differencing scheme We determine the value of φ at the face by linear interpolation between

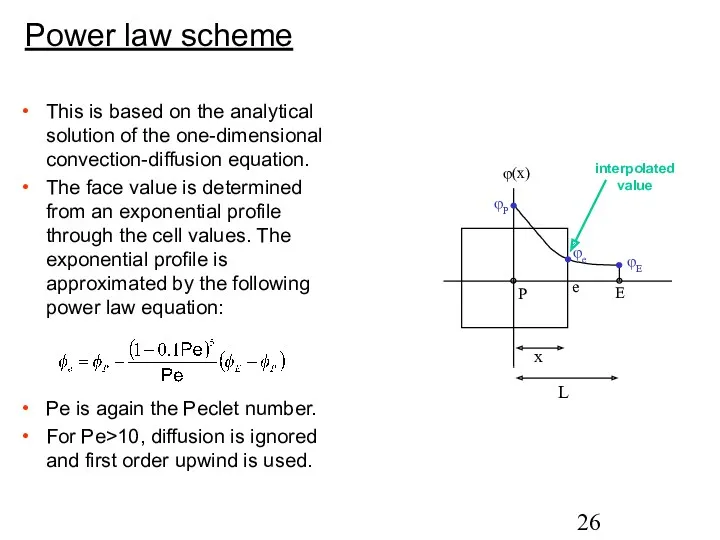

- 26. This is based on the analytical solution of the one-dimensional convection-diffusion equation. The face value is

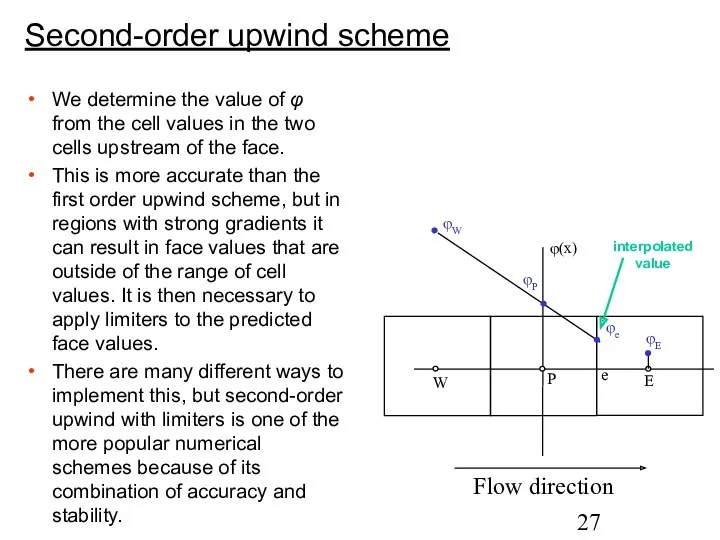

- 27. Second-order upwind scheme We determine the value of φ from the cell values in the two

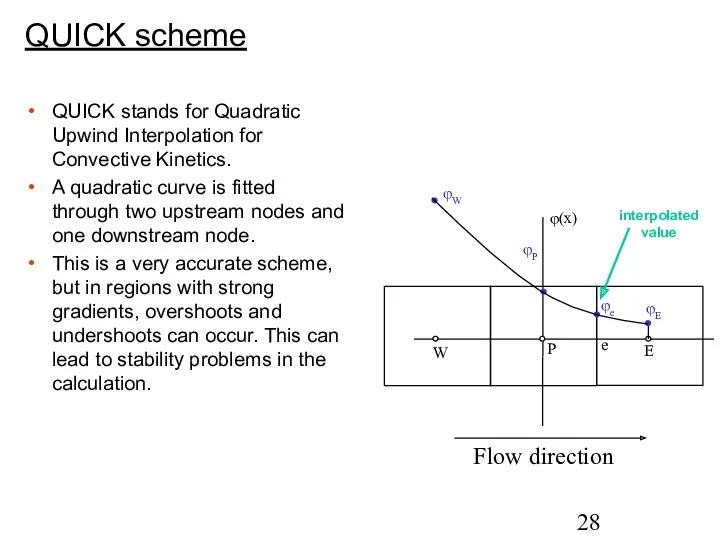

- 28. QUICK scheme QUICK stands for Quadratic Upwind Interpolation for Convective Kinetics. A quadratic curve is fitted

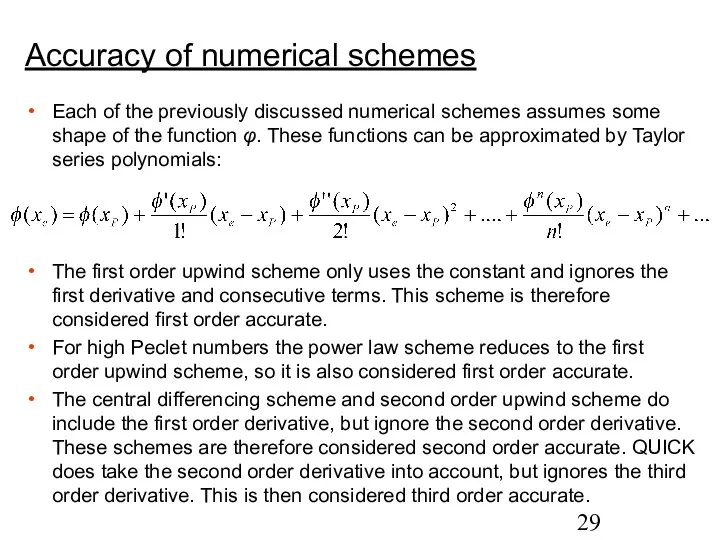

- 29. Accuracy of numerical schemes Each of the previously discussed numerical schemes assumes some shape of the

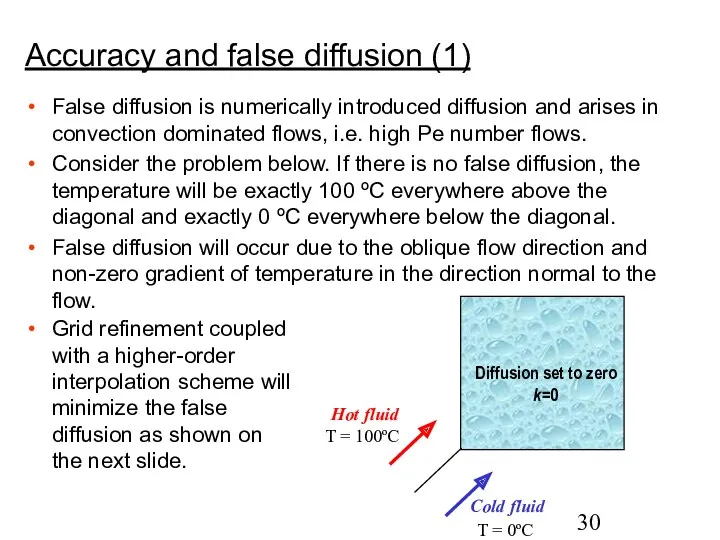

- 30. Accuracy and false diffusion (1) False diffusion is numerically introduced diffusion and arises in convection dominated

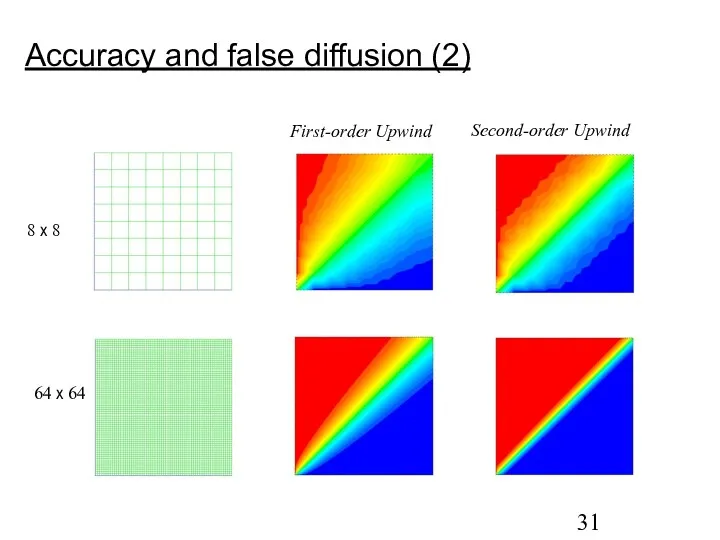

- 31. Accuracy and false diffusion (2)

- 32. Properties of numerical schemes All numerical schemes must have the following properties: Conservativeness: global conservation of

- 33. Solution accuracy Higher order schemes will be more accurate. They will also be less stable and

- 34. Pressure We saw how convection-diffusion equations can be solved. Such equations are available for all variables,

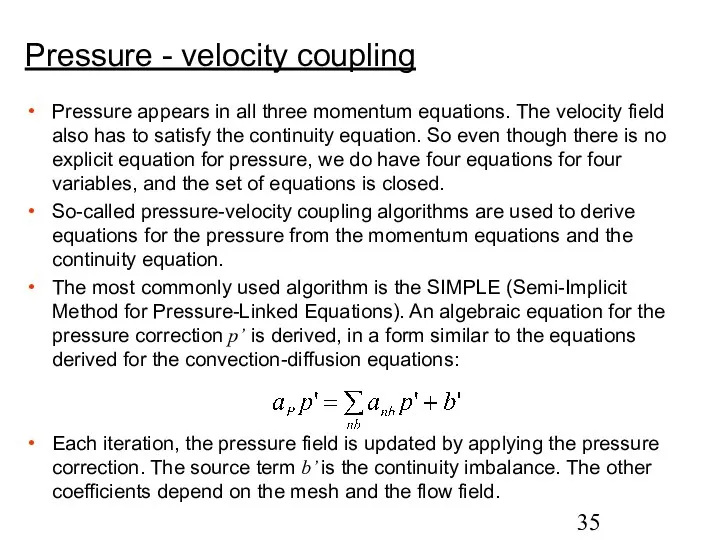

- 35. Pressure - velocity coupling Pressure appears in all three momentum equations. The velocity field also has

- 36. Principle behind SIMPLE The principle behind SIMPLE is quite simple! It is based on the premise

- 37. Improvements on SIMPLE SIMPLE is the default algorithm in most commercial finite volume codes. Improved versions

- 38. Finite volume solution methods The finite volume solution method can either use a “segregated” or a

- 39. Segregated solution procedure

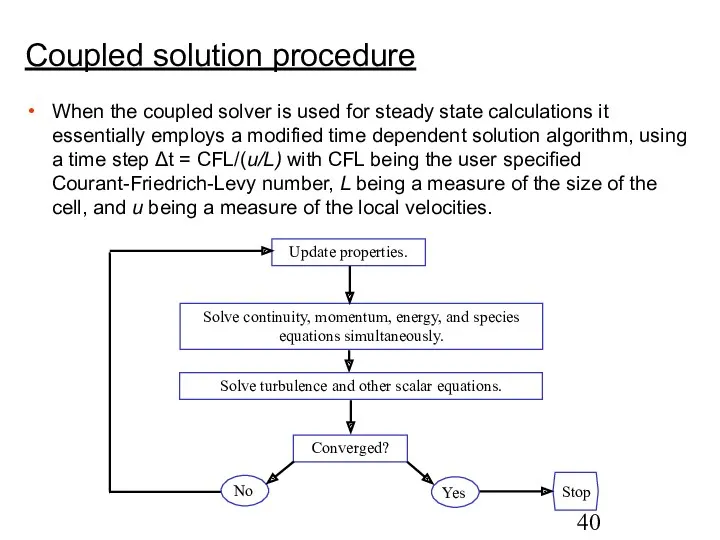

- 40. Coupled solution procedure When the coupled solver is used for steady state calculations it essentially employs

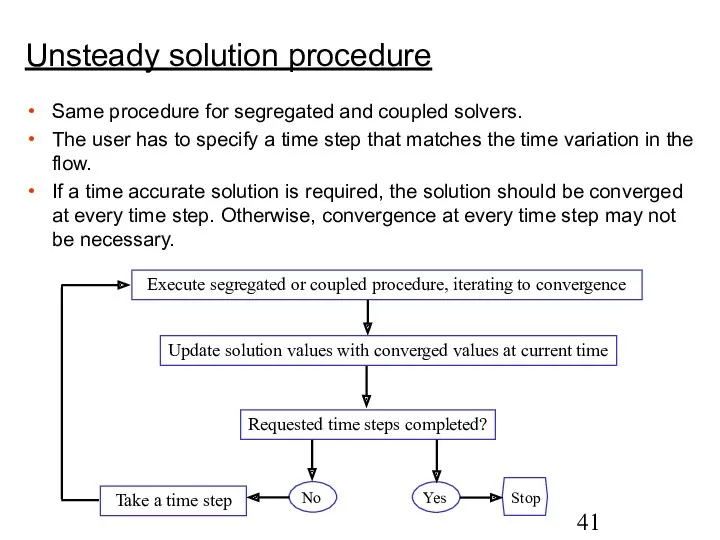

- 41. Unsteady solution procedure Same procedure for segregated and coupled solvers. The user has to specify a

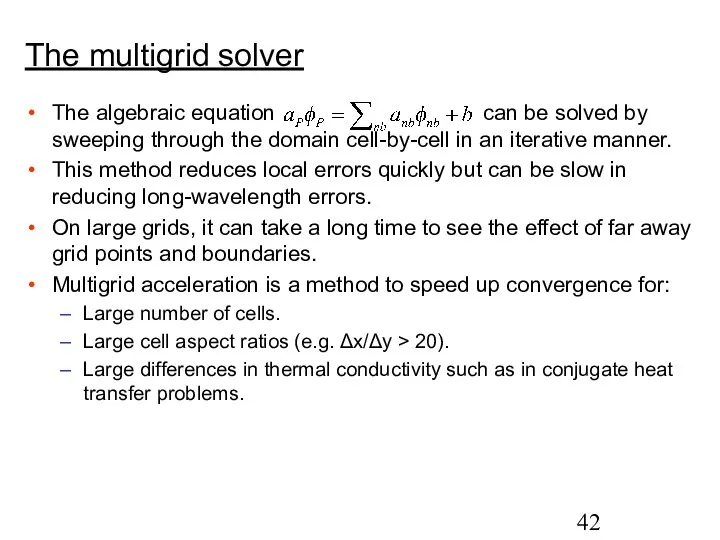

- 42. The multigrid solver The algebraic equation can be solved by sweeping through the domain cell-by-cell in

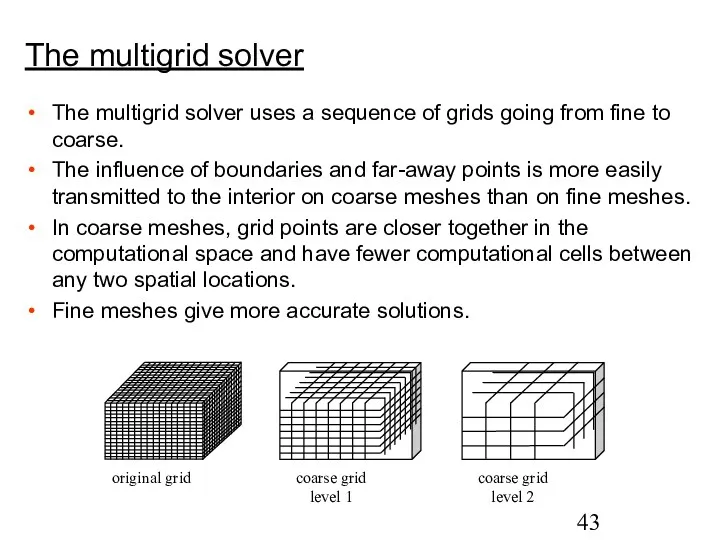

- 43. The multigrid solver uses a sequence of grids going from fine to coarse. The influence of

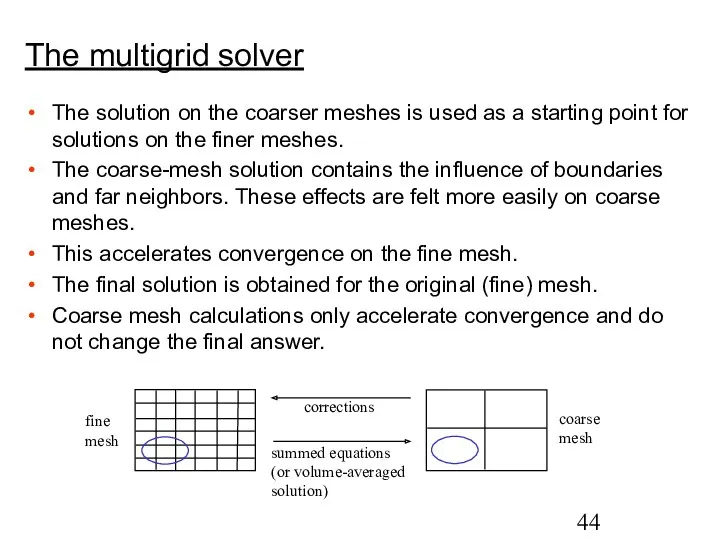

- 44. The solution on the coarser meshes is used as a starting point for solutions on the

- 46. Скачать презентацию

Сложение и вычитание алгебраических дробей

Сложение и вычитание алгебраических дробей Разложение на простые множители

Разложение на простые множители Графики зависимости кинематических величин от времени при равномерном и равноускоренном движении

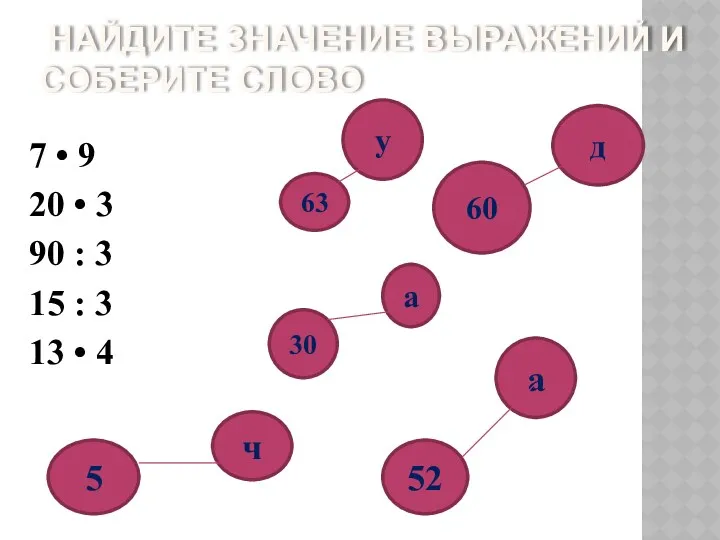

Графики зависимости кинематических величин от времени при равномерном и равноускоренном движении Деление двузначного числа на однозначное.

Деление двузначного числа на однозначное. Применение производной к исследованию функции и построению графика функции

Применение производной к исследованию функции и построению графика функции Таблица умножения и деления на 3

Таблица умножения и деления на 3 Площадь многоугольников

Площадь многоугольников Именованные числа.

Именованные числа. Задачи раскраски графов. Вершинная раскраска

Задачи раскраски графов. Вершинная раскраска Сложение однозначных чисел с переходом через десяток, вида +2, +3

Сложение однозначных чисел с переходом через десяток, вида +2, +3 Параллелограмм. Свойства параллелограмма

Параллелограмм. Свойства параллелограмма Таблица сложения и вычитания в пределах 20 (КИМ 1 класс)

Таблица сложения и вычитания в пределах 20 (КИМ 1 класс) Математика. 1 класс. Урок 7. Порядок

Математика. 1 класс. Урок 7. Порядок Арифметическая прогрессия. Применение формул

Арифметическая прогрессия. Применение формул Урок математики в 3 классе по теме: Деление двузначного числа на однозначное

Урок математики в 3 классе по теме: Деление двузначного числа на однозначное Познавательно-игровой проект Применение игр и игровых упражнений с мячом в работе с детьми Диск

Познавательно-игровой проект Применение игр и игровых упражнений с мячом в работе с детьми Диск Электронные обучающие игры для средней группы: Продолжи ряд, Сколько всего?

Электронные обучающие игры для средней группы: Продолжи ряд, Сколько всего? Теорема синусов. Теорема косинусов

Теорема синусов. Теорема косинусов Урок математики в 1 классе по теме Число пять. Цифра 5.

Урок математики в 1 классе по теме Число пять. Цифра 5. Параллелограмм, трапеция, прямоугольник, квадрат, ромб. Обобщающий урок по геометрии для 8

Параллелограмм, трапеция, прямоугольник, квадрат, ромб. Обобщающий урок по геометрии для 8 Повторение, обобщение и систематизация знаний. Степени с рациональным показателем

Повторение, обобщение и систематизация знаний. Степени с рациональным показателем Формулы - помощники для расчета расстояния, определения скорости движения, времени в пути

Формулы - помощники для расчета расстояния, определения скорости движения, времени в пути Анализ временных рядов. (Тема 5)

Анализ временных рядов. (Тема 5) График линейной функции

График линейной функции Санның логарифмі. Негізгі логарифмдік тепе-теңдік. Логарифмнің қасиеттері

Санның логарифмі. Негізгі логарифмдік тепе-теңдік. Логарифмнің қасиеттері Пифагоров строй

Пифагоров строй Прямая и обратная пропорциональные зависимости

Прямая и обратная пропорциональные зависимости Ryspekov’s Fibonacci sequence formula

Ryspekov’s Fibonacci sequence formula