Содержание

- 2. In our pervious Lecture when discussing Crystals we ASSUMED PERFECT ORDER In real materials we find:

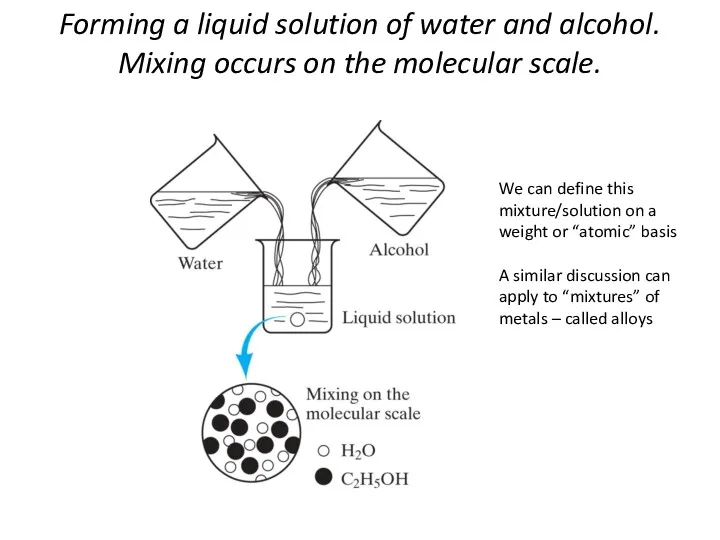

- 3. Forming a liquid solution of water and alcohol. Mixing occurs on the molecular scale. We can

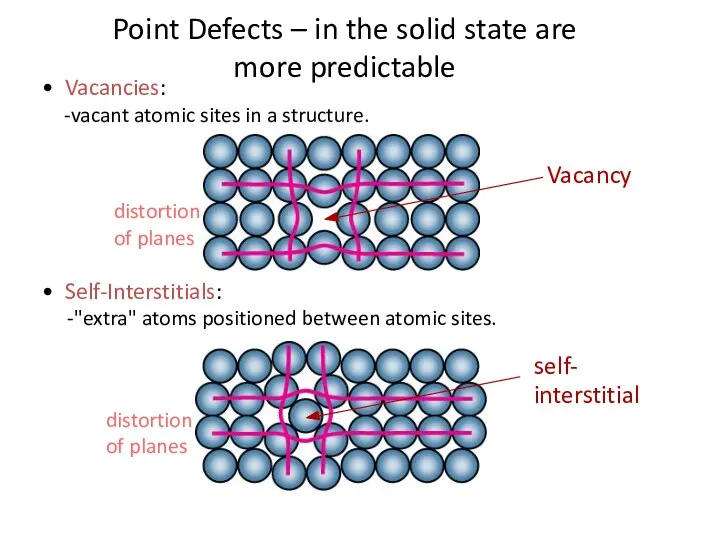

- 4. • Vacancies: -vacant atomic sites in a structure. • Self-Interstitials: -"extra" atoms positioned between atomic sites.

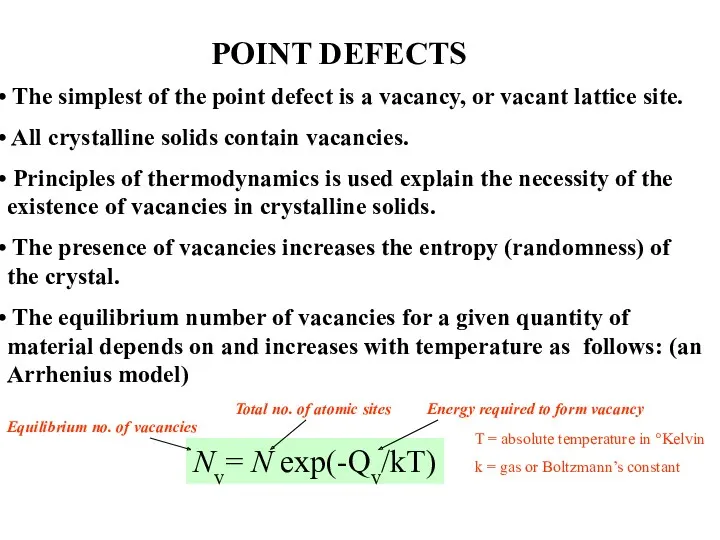

- 5. POINT DEFECTS The simplest of the point defect is a vacancy, or vacant lattice site. All

- 6. Two outcomes if impurity (B) added to host (A): • Solid solution of B in A

- 7. Solid solution of nickel in copper shown along a (100) plane. This is a substitutional solid

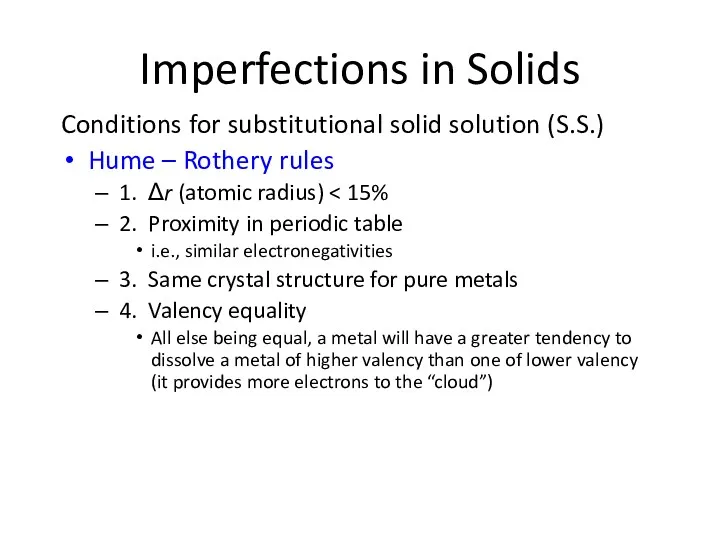

- 8. Imperfections in Solids Conditions for substitutional solid solution (S.S.) Hume – Rothery rules 1. Δr (atomic

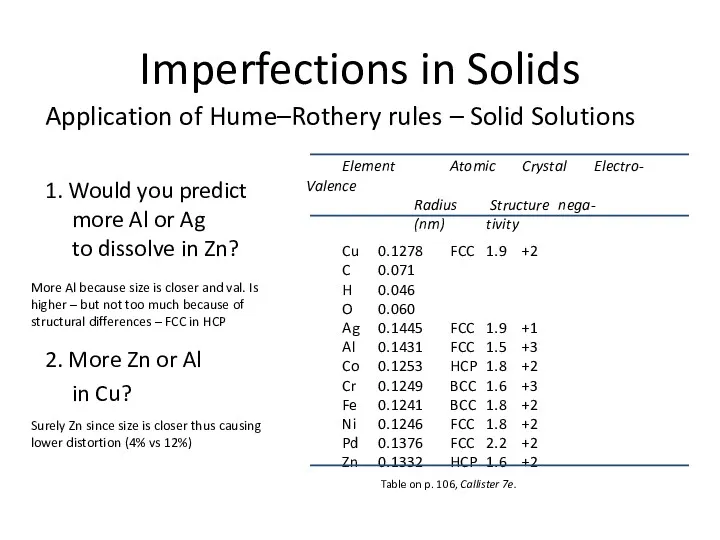

- 9. Imperfections in Solids Application of Hume–Rothery rules – Solid Solutions 1. Would you predict more Al

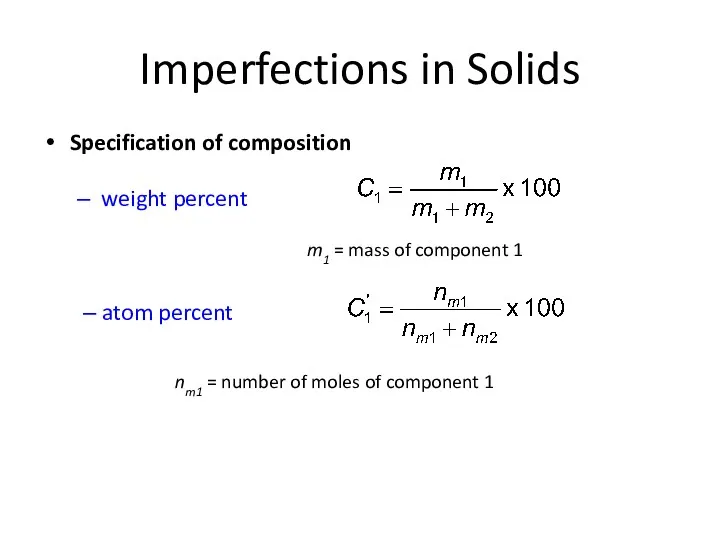

- 10. Imperfections in Solids Specification of composition weight percent m1 = mass of component 1 nm1 =

- 11. Wt. % and At. % -- An example

- 12. Converting Between: (Wt% and At%) Converts from wt% to At% (Ai is atomic weight) Converts from

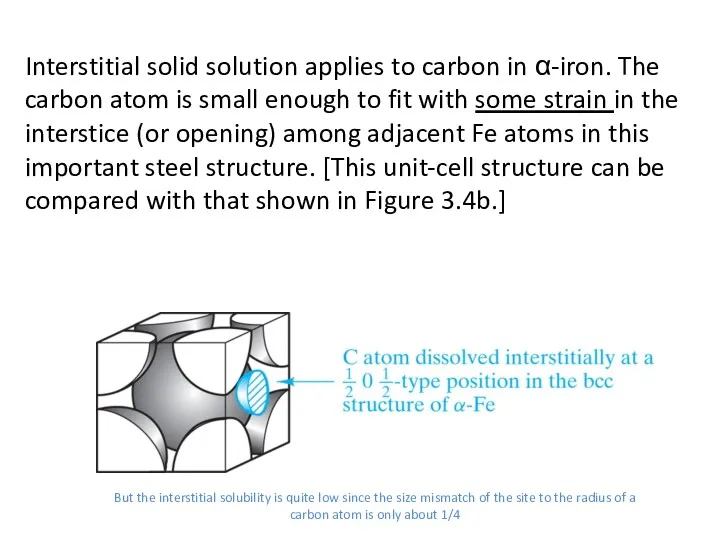

- 13. Interstitial solid solution applies to carbon in α-iron. The carbon atom is small enough to fit

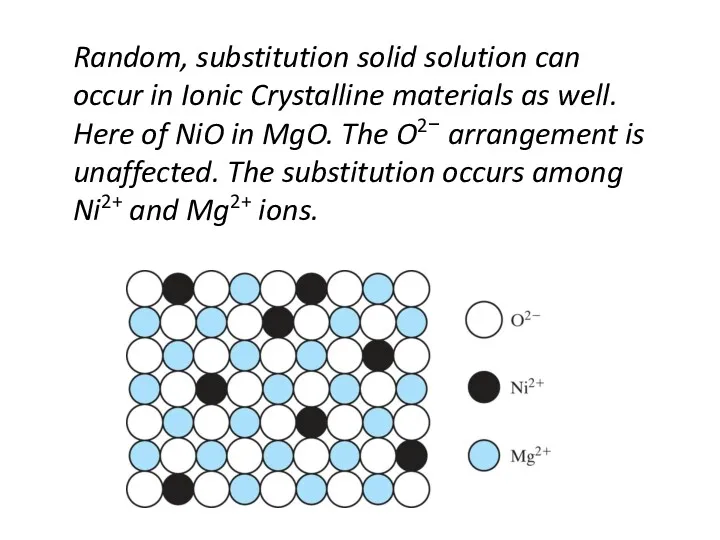

- 14. Random, substitution solid solution can occur in Ionic Crystalline materials as well. Here of NiO in

- 15. A substitution solid solution of Al2O3 in MgO is not as simple as the case of

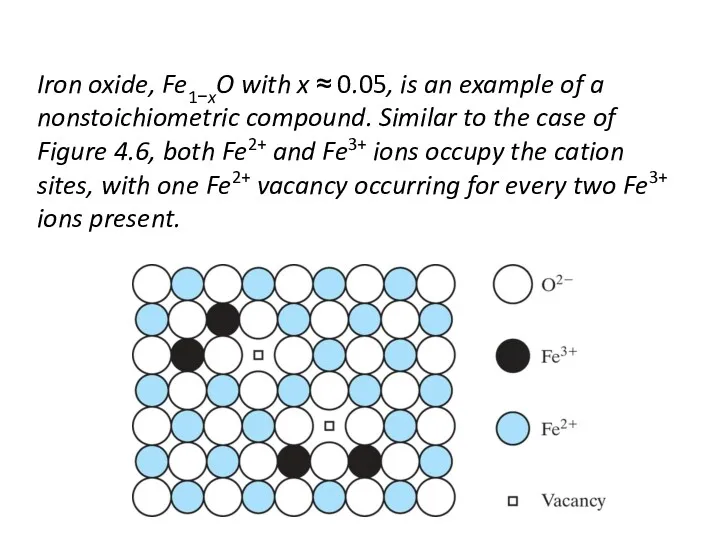

- 16. Iron oxide, Fe1−xO with x ≈ 0.05, is an example of a nonstoichiometric compound. Similar to

- 17. • Frenkel Defect --a cation is out of place. • Shottky Defect --a paired set of

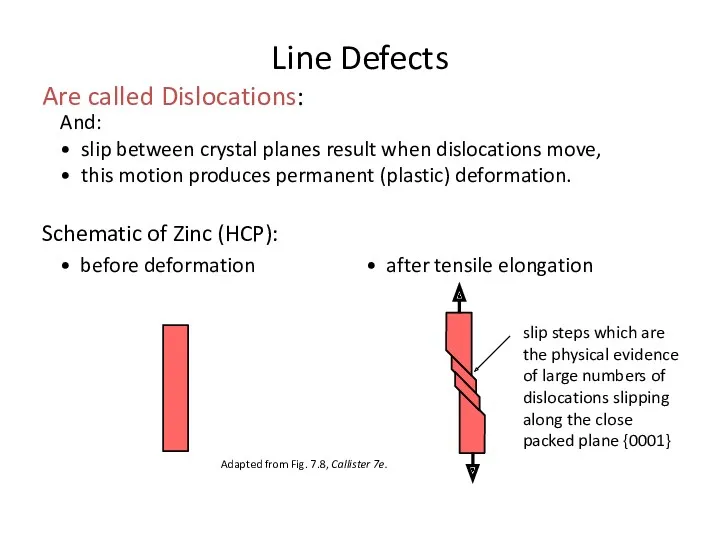

- 18. And: • slip between crystal planes result when dislocations move, • this motion produces permanent (plastic)

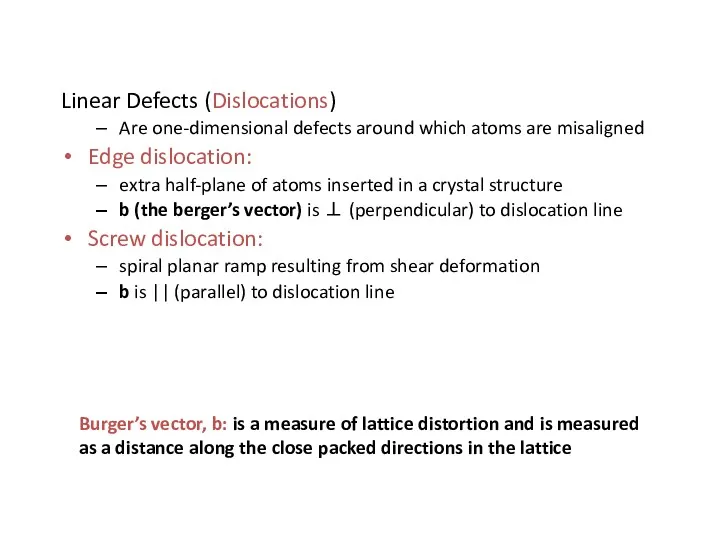

- 19. Linear Defects (Dislocations) Are one-dimensional defects around which atoms are misaligned Edge dislocation: extra half-plane of

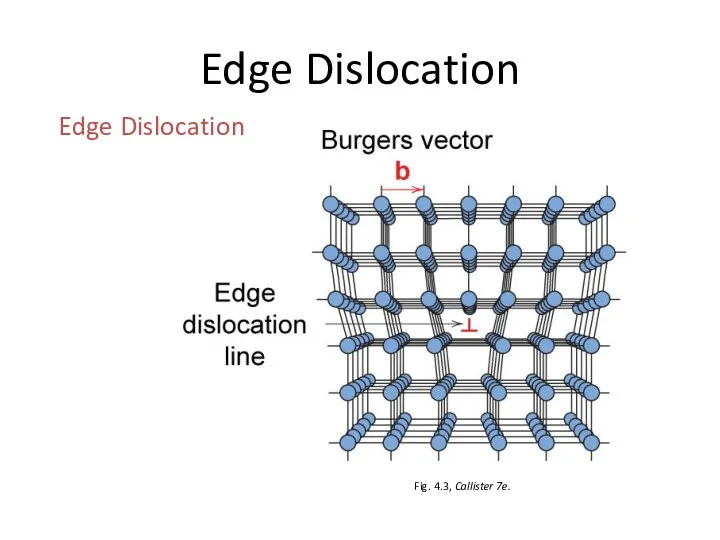

- 20. Edge Dislocation Fig. 4.3, Callister 7e. Edge Dislocation

- 21. Definition of the Burgers vector, b, relative to an edge dislocation. (a) In the perfect crystal,

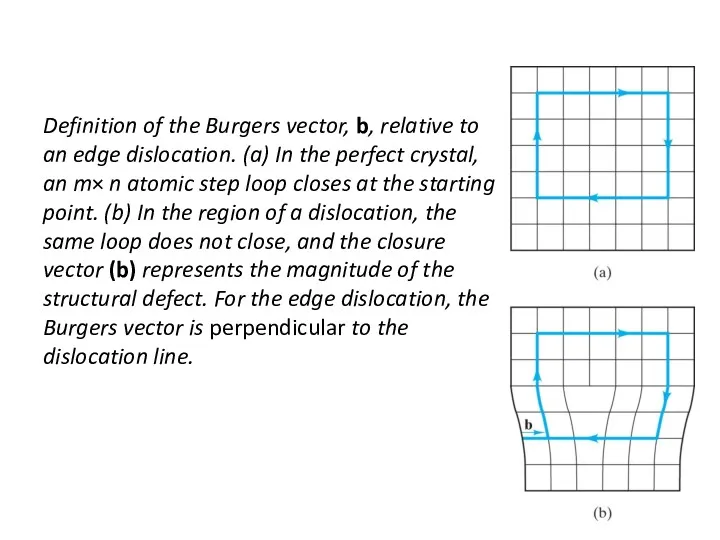

- 22. Screw dislocation. The spiral stacking of crystal planes leads to the Burgers vector being parallel to

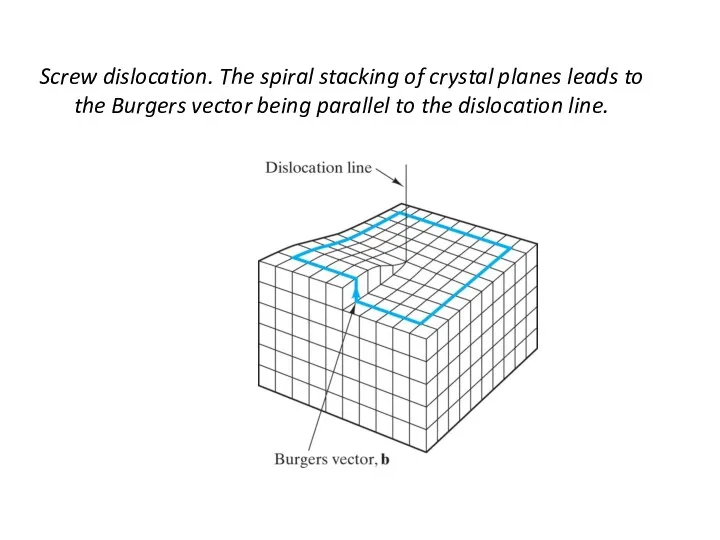

- 23. Mixed dislocation. This dislocation has both edge and screw character with a single Burgers vector consistent

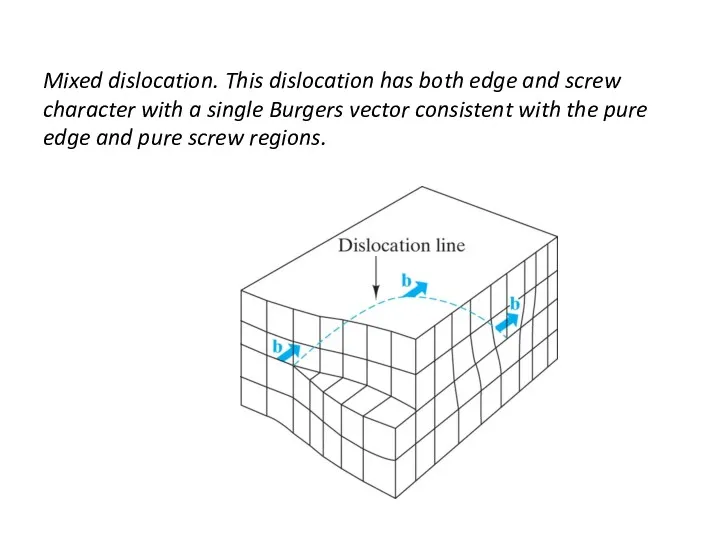

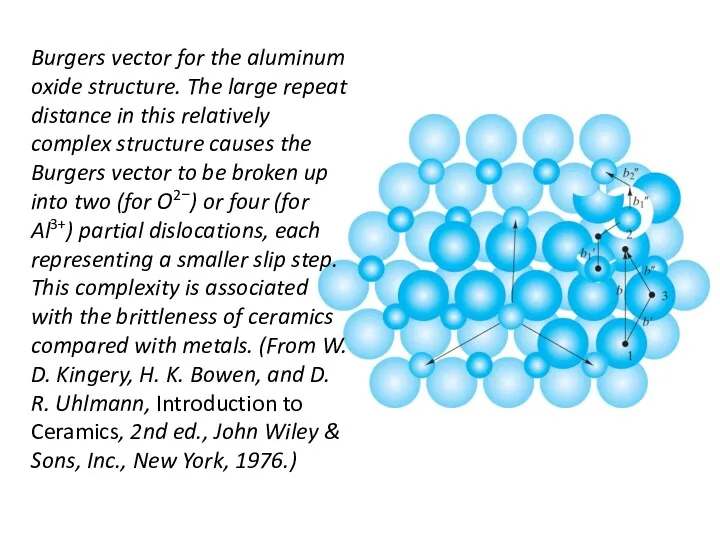

- 24. Burgers vector for the aluminum oxide structure. The large repeat distance in this relatively complex structure

- 25. Imperfections in Solids Dislocations are visible in (T) electron micrographs Adapted from Fig. 4.6, Callister 7e.

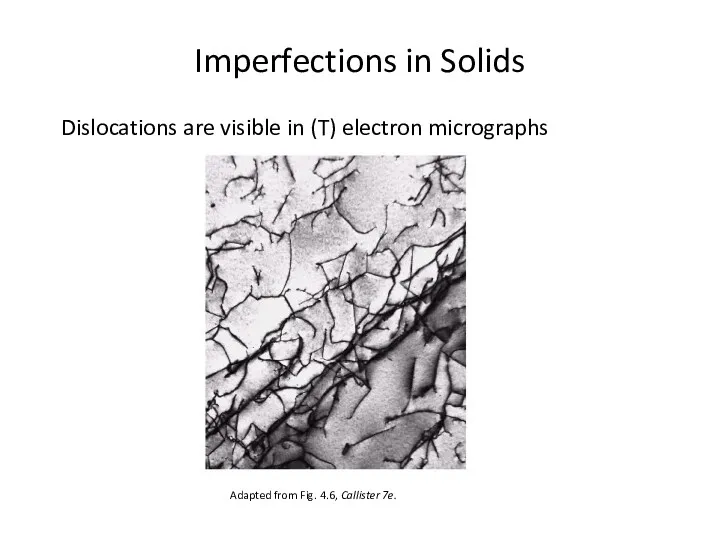

- 26. Dislocations & Crystal Structures • Structure: close-packed planes & directions are preferred. view onto two close-packed

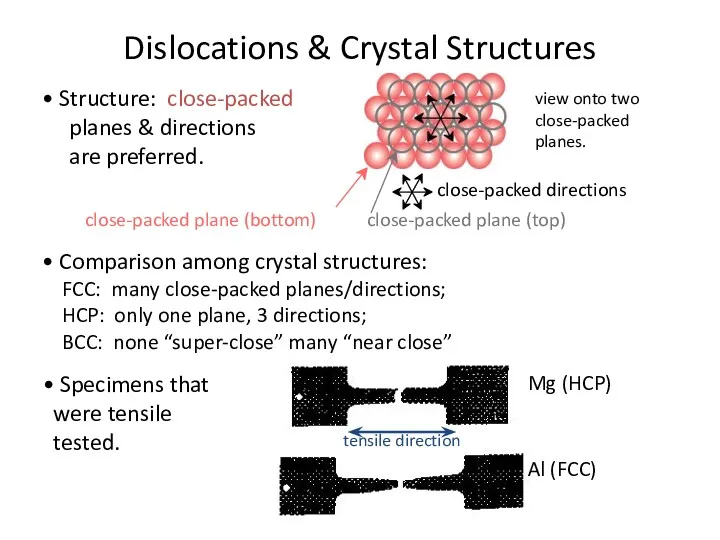

- 27. One case is a twin boundary (plane) Essentially a reflection of atom positions across the twinning

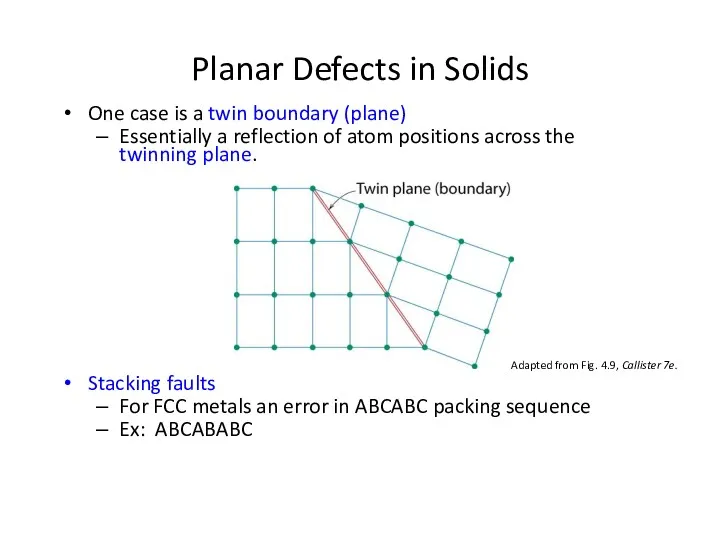

- 28. Simple view of the surface of a crystalline material.

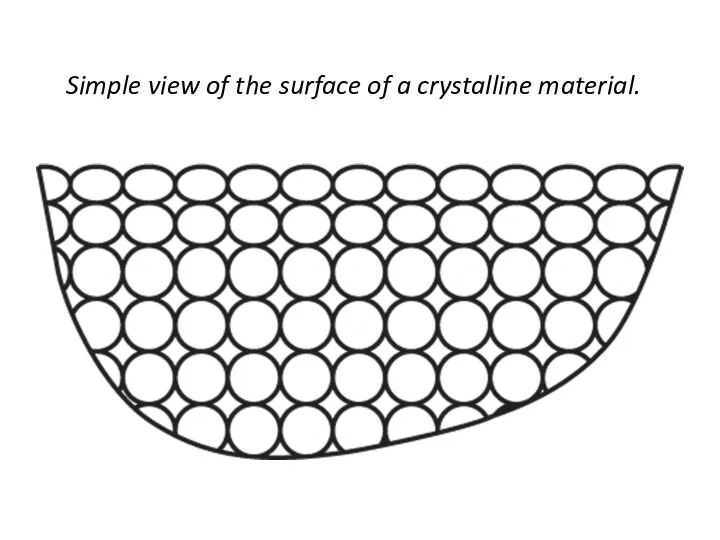

- 29. A more detailed model of the elaborate ledgelike structure of the surface of a crystalline material.

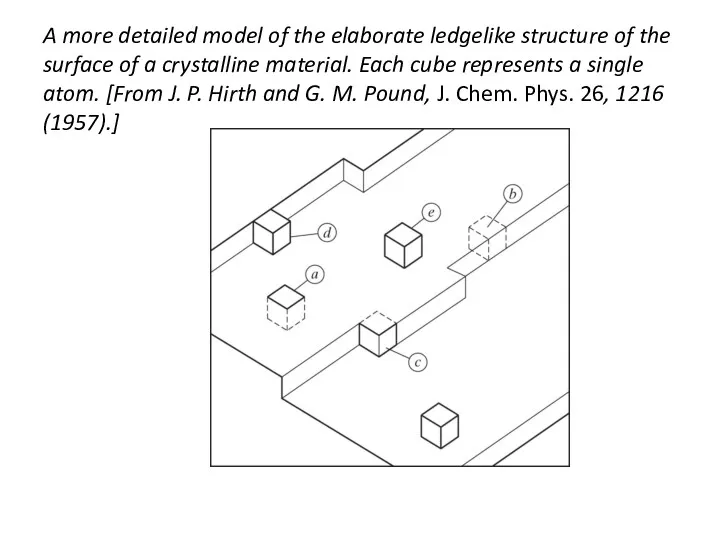

- 30. Typical optical micrograph of a grain structure, 100×. The material is a low-carbon steel. The grain

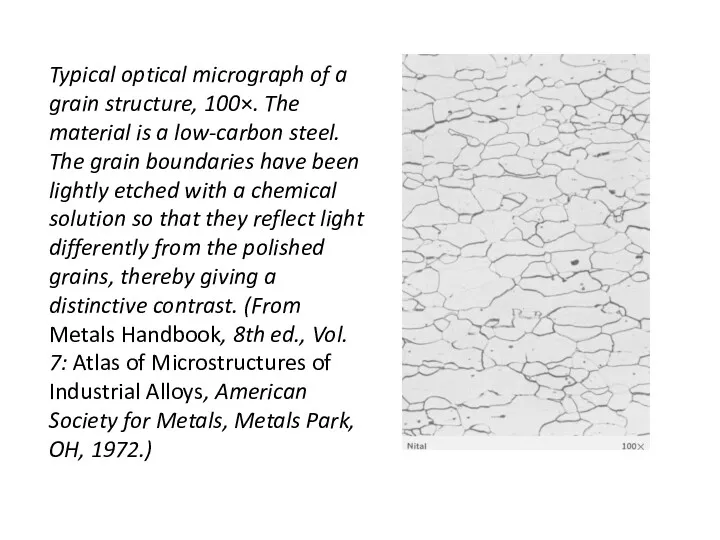

- 31. Simple grain-boundary structure. This is termed a tilt boundary because it is formed when two adjacent

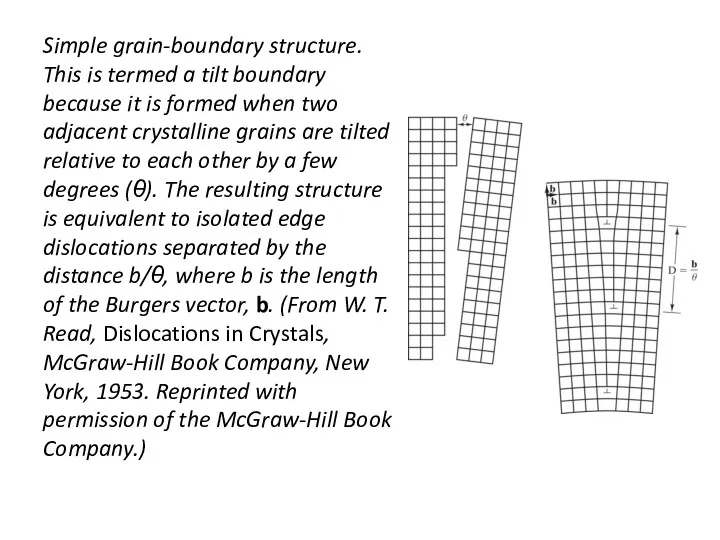

- 32. The ledge Growth leads to structures with Grain Boundries The shape and average size or diameter

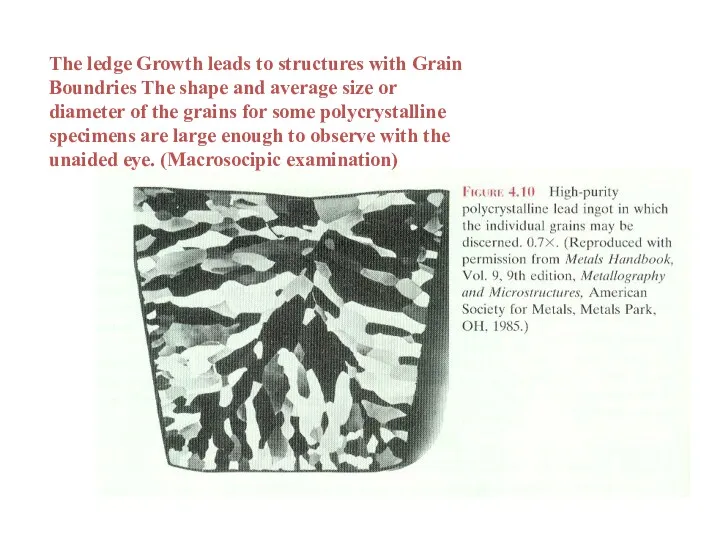

- 33. Specimen for the calculation of the grain-size number, G is defined at a magnification of 100×.

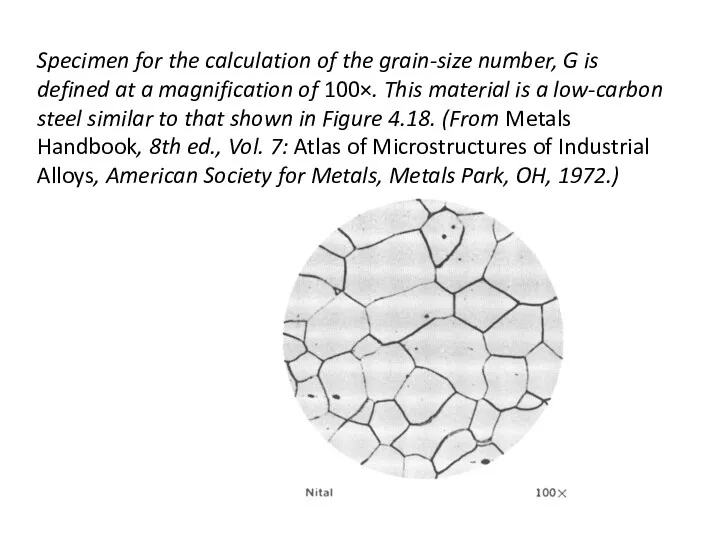

- 34. • Useful up to ~2000X magnification (?). • Polishing removes surface features (e.g., scratches) • Etching

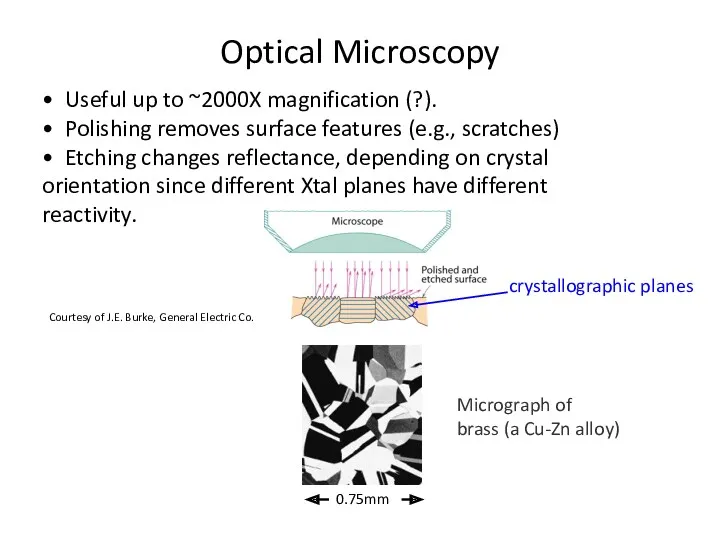

- 35. Since Grain boundaries... • are planer imperfections, • are more susceptible to etching, • may be

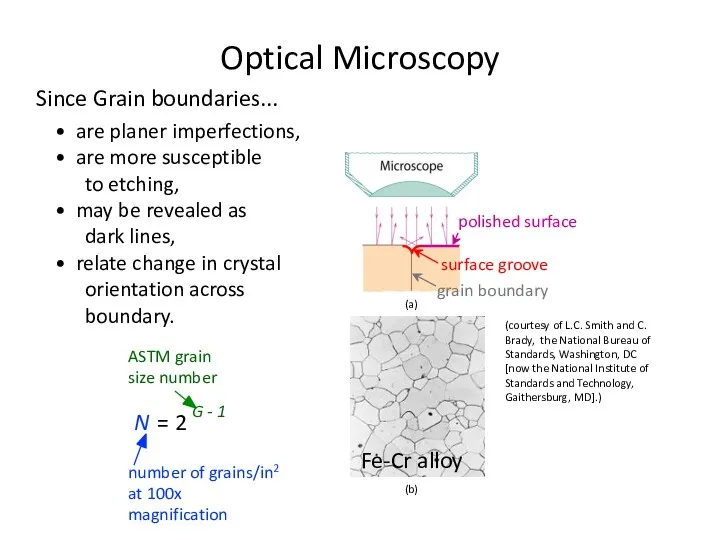

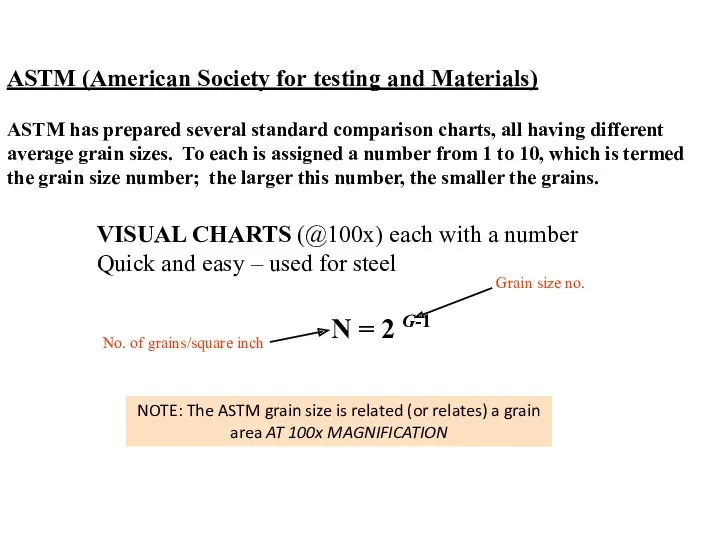

- 36. ASTM (American Society for testing and Materials) VISUAL CHARTS (@100x) each with a number Quick and

- 37. Determining Grain Size, using a micrograph taken at 300x We count 14 grains in a 1

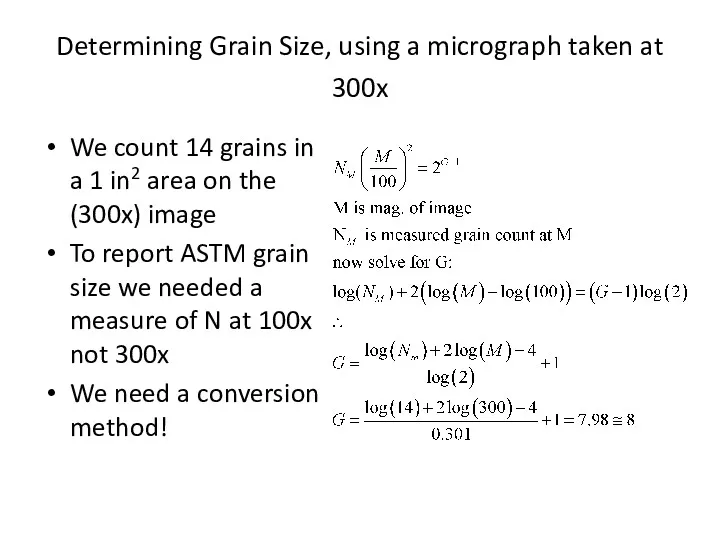

- 38. For this same material, how many Grains would I expect /in2 at 100x? At 50x?

- 39. At 100x

- 40. Two-dimensional schematics give a comparison of (a) a crystalline oxide and (b) a non-crystalline oxide. The

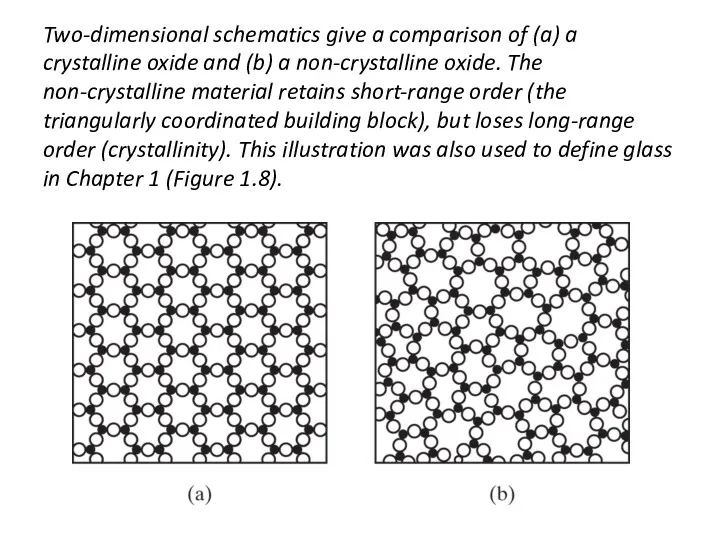

- 41. Bernal model of an amorphous metal structure. The irregular stacking of atoms is represented as a

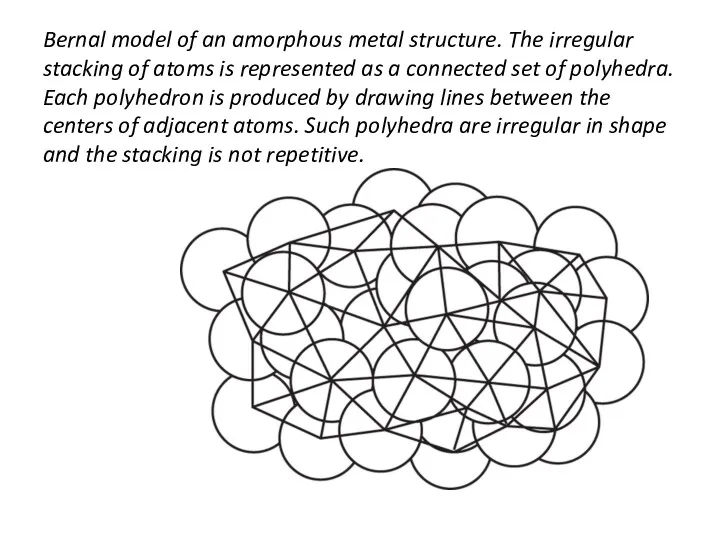

- 42. A chemical impurity such as Na+ is a glass modifier, breaking up the random network and

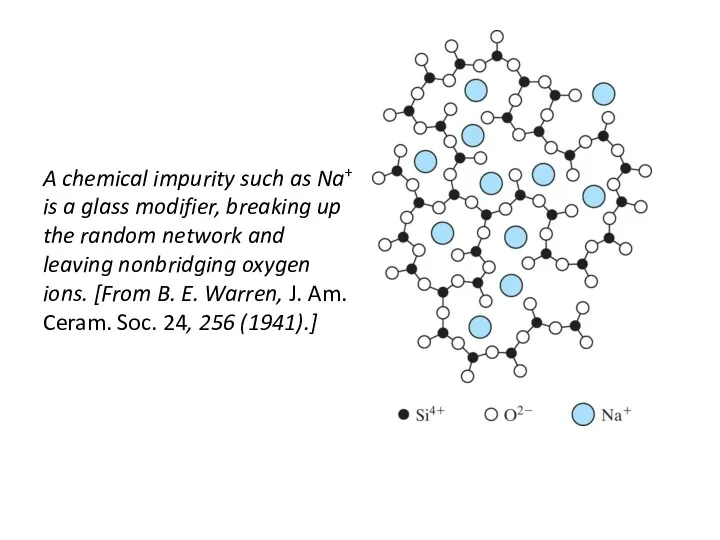

- 43. Schematic illustration of medium-range ordering in a CaO–SiO2 glass. Edge-sharing CaO6 octahedra have been identified by

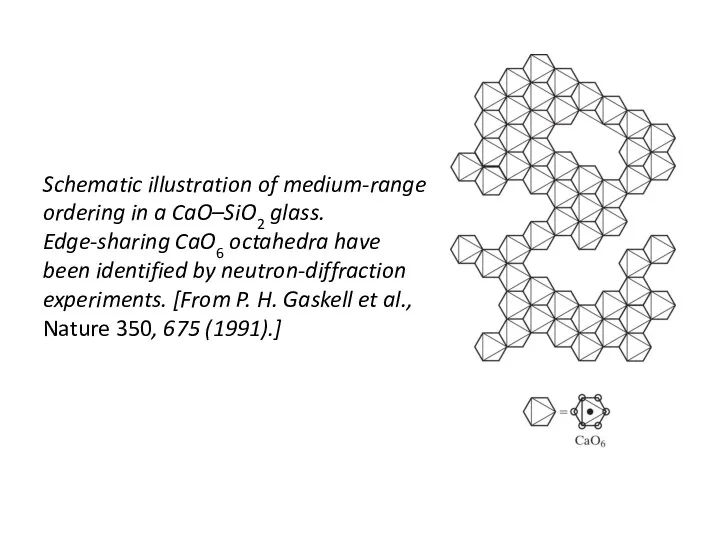

- 45. Скачать презентацию

Основные понятия органической химии

Основные понятия органической химии Закон Авогадро. Молярный объем газов

Закон Авогадро. Молярный объем газов Нанотехнологии в школьном образовании. Семинар учителей химии

Нанотехнологии в школьном образовании. Семинар учителей химии Геохимические барьеры

Геохимические барьеры Высокомолекулярные соединения. Общий курс

Высокомолекулярные соединения. Общий курс Фунгициды. Достоинства и недостати

Фунгициды. Достоинства и недостати Кристаллические решетки. (8 класс)

Кристаллические решетки. (8 класс) Стереоселективные синтезы

Стереоселективные синтезы Оптические свойства и методы исследования дисперсных систем. Лекция 16

Оптические свойства и методы исследования дисперсных систем. Лекция 16 Электрондардың атомдарда орналасуы

Электрондардың атомдарда орналасуы Химия вокруг нас

Химия вокруг нас Выделение ферментных препаратов методами осаждения и высаливания

Выделение ферментных препаратов методами осаждения и высаливания Механическая смесь и растворы

Механическая смесь и растворы Аминокислоты алифатического ряда и их производные

Аминокислоты алифатического ряда и их производные Аминокислоты и белки

Аминокислоты и белки Методы получения органических галогенидов

Методы получения органических галогенидов Поверхностные явления

Поверхностные явления Фармацевтическая химия натрия гидрокарбоната

Фармацевтическая химия натрия гидрокарбоната Азотные удобрения

Азотные удобрения Номенклатура углеводородов: алканов алкенов алкинов. Создание учебного пособия

Номенклатура углеводородов: алканов алкенов алкинов. Создание учебного пособия Коррозия каменных и бетонных строительных конструкций

Коррозия каменных и бетонных строительных конструкций Химическая связь. Взаимное влияние атомов в молекуле. Классификация реакций и реагентов. Структура и функции биолекул

Химическая связь. Взаимное влияние атомов в молекуле. Классификация реакций и реагентов. Структура и функции биолекул Общие правила техники безопасности при работе в кабинете химии. Урок №2. Практическая работа №1

Общие правила техники безопасности при работе в кабинете химии. Урок №2. Практическая работа №1 Побочная подгруппа VIII группы периодической системы

Побочная подгруппа VIII группы периодической системы Химическая связь и ее типы. (11 класс)

Химическая связь и ее типы. (11 класс) Особенности сжигания жидкого топлива и топливосжигающие устройства

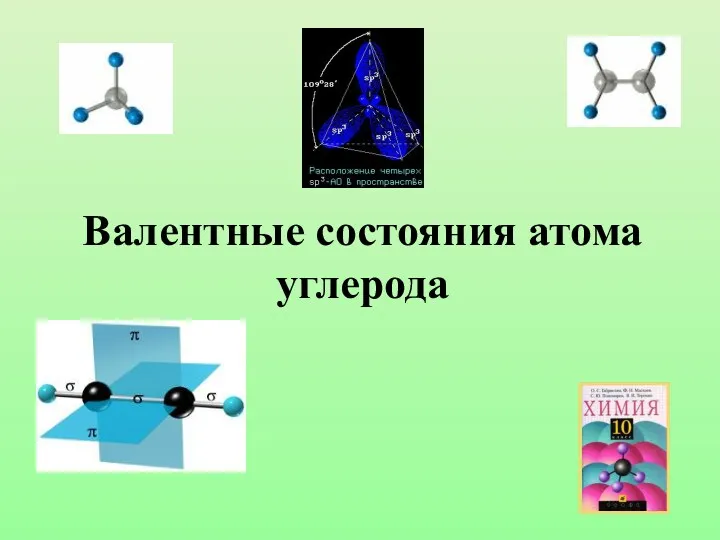

Особенности сжигания жидкого топлива и топливосжигающие устройства Валентные состояния атома углерода

Валентные состояния атома углерода Химическая промышленность России

Химическая промышленность России