Содержание

- 2. MAIN QUESTIONS Which source of law will take precedence in case of conflict between EU law

- 3. ORIGINAL SITUATION (THE TREATIES) The founding Treaties did not directly address these questions. The Member States

- 4. ORIGINAL SITUATION (THE TREATIES) (2) In dualist States (such as the UK), international law is only

- 5. ROLE OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF JUSTICE In monist States (such as NL, FR), once ratified,

- 7. THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY OF UNION LAW

- 8. THE CREATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY While the Court did not address the issue of

- 9. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY The implications of the doctrine of supremacy were not

- 10. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (2) The Court provided a number of arguments in

- 11. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (3) In addition, the Court argued that the obligations

- 12. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (4) While Van Gend and Costa dealt with the

- 13. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (5) The ECJ made it clear that EU law

- 14. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (6) In Case 106/77, Amministrazione delle Finanze dello Stato

- 15. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (7) This judgment is important, in that it confers

- 16. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF SUPREMACY (8) A further example of the jurisdiction of national

- 18. THE DOCTRINE OF DIRECT EFFECT OF EU LAW

- 19. THE CREATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF DIRECT EFFECT The ECJ provided a ground-breaking judgment in Case

- 20. THE CREATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF DIRECT EFFECT (2) In order to arrive at its decision,

- 21. THE CREATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF DIRECT EFFECT (3) In other words, the Court of Justice

- 22. THE CONDITIONS FOR DIRECT EFFECT (VAN GEND CRITERIA) The Court explained in Van Gend that not

- 23. VAN GEND CRITERION N. 1 clear and precise it is logical that if law is to

- 24. VAN GEND CRITERION N. 2 unconditional a provision will not be unconditional if the right it

- 25. VAN GEND CRITERION N. 3 not subject to any further implementing measures on the part of

- 27. DIRECT EFFECT OF DIFFERENT SOURCES OF UNION LAW

- 28. DIRECT EFFECT AND TREATY ARTICLES The question of whether the principle of direct effect applies to

- 29. DIRECT EFFECT AND REGULATIONS Article 288 TFEU would appear to give regulations direct effect. The Article

- 30. DIRECT EFFECT AND DECISIONS Decisions, as regulations, are directly applicable, but Art 288 TFEU provides that

- 31. DIRECT EFFECT OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS In an attempt to ensure that Member States respect any commitments

- 32. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES This is a particularly controversial area. Article 288 TFEU provides that: ‘A

- 33. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES (2) The wording of Art 288 TFEU seems to preclude directives from

- 34. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES (3) The Court has argued that this approach results in directives being

- 35. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES (4) In response to such criticism, the ECJ has explained that directives

- 36. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES (5) The ET made a preliminary reference to the ECJ (under Art

- 37. DIRECT EFFECT AND DIRECTIVES (6) This requirement has the unfortunate effect of discriminating between individuals who

- 38. DEVELOPING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DIRECTIVES

- 39. VERTICAL DIRECT EFFECT: A WIDE INTERPRETATION OF ‘STATE’ To address the problem highlighted above, the ECJ

- 40. VERTICAL DIRECT EFFECT: A WIDE INTERPRETATION OF ‘STATE’ (2) In Case C-188/89, Foster v British Gas,

- 41. VERTICAL DIRECT EFFECT: A WIDE INTERPRETATION OF ‘STATE’ (3) This conclusion is supported by the Court

- 42. INDIRECT EFFECT OR THE ‘INTERPRETIVE OBLIGATION’

- 43. INDIRECT EFFECT The ECJ’s refusal to allow the horizontal direct effect of directives has without doubt

- 44. THE BASIC PRINCIPLE OF INDIRECT EFFECT In Case 14/83, Von Colson, the Court reminded Member States

- 45. THE BASIC PRINCIPLE OF INDIRECT EFFECT (2) This judgment has been the subject of much academic

- 46. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF INDIRECT EFFECT The Von Colson judgment left a number of

- 47. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF INDIRECT EFFECT (2) In Case C-106/89, Marleasing, the ECJ confirmed

- 48. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF INDIRECT EFFECT (3) However, the decision in Marleasing has been

- 49. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DOCTRINE OF INDIRECT EFFECT (4) Academics have highlighted that indirect effect is

- 50. ‘INCIDENTAL’ OR ‘TRIANGULAR’ EFFECT Despite the Court of Justice’s decision in Marshall (No 1) prohibiting the

- 51. ‘INCIDENTAL’ OR ‘TRIANGULAR’ EFFECT (2) Once more, the ECJ cited the enhanced effectiveness of directives as

- 52. ADDITIONAL THOUGHTS ON THE SOURCE OF AN EU RIGHT OR OBLIGATION While the matter of the

- 53. STATE LIABILITY FOR DAMAGES (THE FRANCOVICH PRINCIPLE)

- 54. In view of the limitations placed on the direct effect of directives, and despite the possibility

- 55. In Cases C-6 and 9/90, Francovich and Bonifaci v Italy (Francovich), the Court of Justice held

- 56. THE DEVELOPMENT OF STATE DAMAGES The Francovich ruling has been of immense importance to Union law

- 57. Once more, however, the Court explained that certain criteria must be fulfilled: the rule of law

- 58. THE COURT OF JUSTICE’S INTERPRETATION OF ‘SUFFICIENTLY SERIOUS’ With regard to what will constitute a ‘sufficiently

- 59. EXPANSION OF THE PRINCIPLE TO ACTIONS AGAINST PRIVATE PARTIES In addition to the Francovich principle being

- 60. TO RECAPITULATE:

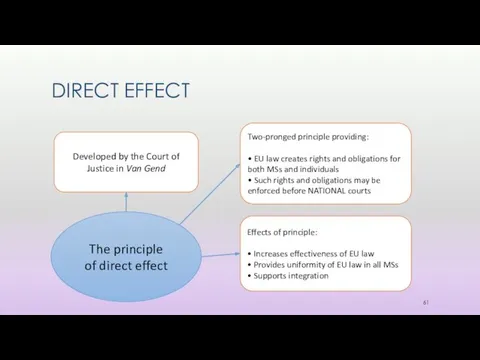

- 61. DIRECT EFFECT The principle of direct effect Developed by the Court of Justice in Van Gend

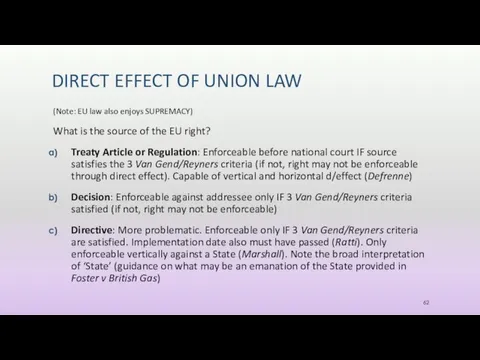

- 62. DIRECT EFFECT OF UNION LAW (Note: EU law also enjoys SUPREMACY) What is the source of

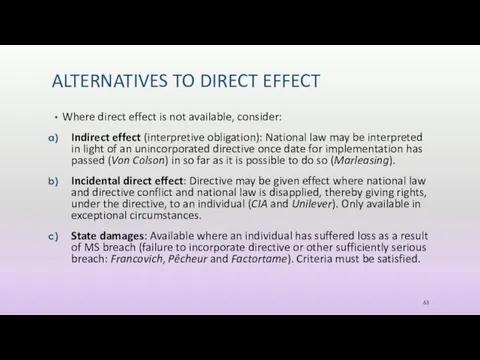

- 63. ALTERNATIVES TO DIRECT EFFECT Where direct effect is not available, consider: Indirect effect (interpretive obligation): National

- 65. Скачать презентацию

Тема 1.6.3

Тема 1.6.3 Соседи Солнца. Планеты земной группы. Планеты - гиганты и маленький Плутон.Природоведение 5 класс (к учебнику А.А.Плешакова.Н.И.Сонина).

Соседи Солнца. Планеты земной группы. Планеты - гиганты и маленький Плутон.Природоведение 5 класс (к учебнику А.А.Плешакова.Н.И.Сонина). Однородные члены предложения

Однородные члены предложения Гибридизация атомных орбиталей.

Гибридизация атомных орбиталей. Опыт работы организации родительского просвещения РИМЦ Краснокамского муниципального района

Опыт работы организации родительского просвещения РИМЦ Краснокамского муниципального района Micro Fabrication Basics

Micro Fabrication Basics Подготовка электрического кабеля связи к монтажу

Подготовка электрического кабеля связи к монтажу Презентация детского коллектива Радуга

Презентация детского коллектива Радуга Родительское собрание в 1 классе

Родительское собрание в 1 классе Тригонометрические функции числового аргумента

Тригонометрические функции числового аргумента Виды соединений. Сборка изделий из тонколистового металла, проволоки, искусственных материалов. 5 класс

Виды соединений. Сборка изделий из тонколистового металла, проволоки, искусственных материалов. 5 класс Вводная лекция по специальности: товаровед - приемщик ломбарда

Вводная лекция по специальности: товаровед - приемщик ломбарда Efes Manufacturing System

Efes Manufacturing System Священные книги религий мира. Тора, Библия, Коран

Священные книги религий мира. Тора, Библия, Коран Презентация Металлы

Презентация Металлы Элементы налогообложения

Элементы налогообложения Урок по изучению Республики Мордовия по теме Важнейшие объекты (природные, хозяйственные, культурные) РМ

Урок по изучению Республики Мордовия по теме Важнейшие объекты (природные, хозяйственные, культурные) РМ Памятка по предоставлению земельных участков в безвозмездное пользование

Памятка по предоставлению земельных участков в безвозмездное пользование Экономическое содержание собственности

Экономическое содержание собственности Презентация по Волшебнику изумрудного города

Презентация по Волшебнику изумрудного города Многогранники. Геометрические понятия

Многогранники. Геометрические понятия Презентация о счастье

Презентация о счастье Тема : Сказочный мир цветов - классный час.

Тема : Сказочный мир цветов - классный час. Родительское собрание на тему Токсикомания

Родительское собрание на тему Токсикомания Презентация практической работы Анализ фотографий , рисунков, картин

Презентация практической работы Анализ фотографий , рисунков, картин Какие болезни называют инвазионными?

Какие болезни называют инвазионными? Постижение самого себя

Постижение самого себя Объемные насосы

Объемные насосы